Economic cost of violence against women and their children

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Analysis foundations

- Prevalence of reported violence

- Pain, suffering and premature mortality

- Health costs

- Production-related costs

- Consumption-related costs

- Administrative and other costs

- Second generation costs

- Transfer costs

- Non-domestic violence

- The impact of violence on vulnerable groups

Overview

The cost of inaction

Violence against women and their children will cost the Australian economy an estimated $13.6 billion this year1. Without appropriate action to address violence against women and their children2, an estimated three-quarters of a million Australian women will experience and report violence in the period of 2021-22, costing the Australian economy an estimated $15.6 billion3. This is more than last year’s $10.4 billion plan by the Australian Government to stimulate the economy in the face of the global financial crisis; more than the Government's $5.9 billion Education Revolution; and more than three-quarters of the initial budget allocation in 2008-09 of $20 billion to its Building Australia Fund.

Implementation of Time for Action: The National Council’s Plan for Australia to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children (the Plan of Action) aims to reduce the levels of violence against women and their children by 2021. For every woman whose experience of violence can be prevented by the Plan of Action, $20,766 in costs across all affected groups in society are avoided.

To place this in perspective, if the Plan of Action resulted in an average reduction in violence against women and their children of just 10 per cent by 2021-22, some $1.6 billion in costs to victims/survivors, their friends and families, perpetrators, children, employers, governments and the community could be avoided.

The Plan of Action

Violence against women and their children remains a profound problem and addressing it is one of the greatest challenges for Australia. Around one in three Australian women experience physical violence, and almost one in five women experience sexual violence over their lifetime4.

In May 2008, the Australian Government established the National Council to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children (the Council) to provide expert advice on measures to reduce the incidence and impact of sexual assault and domestic and family violence. The first task for the Council was to develop a national plan of action.

The Plan of Action describes the commitment and actions needed to guide all Australians, their governments and communities in reducing violence against women and their children. Implementing the Plan of Action is central to achieving the Government’s priorities for women.

The Plan of Action sets out an action agenda until 2021. This timeframe recognises the need for long-term investment and commitment in order to achieve long-term and sustainable change. The aim of this report is to provide indicative estimates of the cost of violence against women and their children in 2021-22 without appropriate action, and the costs that could be avoided by reducing levels of violence.

The cost of violence against women and their children

Violence against women and their children carries an enormous economic cost to society. The cost of domestic violence in Australia was estimated at $8.1 billion in 2002-03, comprising $3.5 billion in costs attributable to pain, suffering and premature mortality. The largest cost burden of domestic violence was borne by victims/survivors ($4 billion)5.

This report updates the 2002-03 cost estimates and projects the costs to 2021 226. In updating the estimates, the most recent data has been used as a basis for updating the costs, and in other cases an appropriate escalation factor has been applied (rather than replicating the construction of these costs).

The scope and effort implied in constructing the 2002-03 estimates far exceeds that of this study. The aim is to provide decision-makers with a sense of the scale of this problem and its impact on society, in order to provide another perspective on the need for and benefits of intervention as advocated by the Plan of Action.

The estimates of cost savings are not linked to specific initiatives contained in the Plan of Action. This report does not contain views on the cost-effectiveness of specific initiatives proposed in the Plan of Action. These are areas that could be considered as part of a detailed business case for investment.

Cost categories

There are seven cost categories that comprise the headline cost estimate. These are:

- Pain, suffering and premature mortality costs associated with the victims/survivors experience of violence.

- Health costs include public and private health system costs associated with treating the effects of violence against women.

- Production-related costs, including the cost of being absent from work, and employer administrative costs (for example, employee replacement).

- Consumption-related costs, including replacing damaged property, defaulting on bad debts, and the costs of moving.

- Second generation costs are the costs of children witnessing and living with violence, including child protection services and increased juvenile and adult crime, which are the inefficiencies associated with the payment of government benefits.

- Administrative and other costs, including police, incarceration, court system costs, counselling, and violence prevention programs.

- Transfer costs, which are the inefficiencies associated with government benefits such as victim/survivor compensation and lost taxes.

The costs are allocated across eight groups within society which bear the costs of violence. These are: victims/survivors; perpetrators; children; friends and family; employers; federal, state/territory and local government; and the rest of the community/society (non-government). Further details, including cost category descriptions and details on the approach taken to update and forecasts these costs, are in the Appendix to this report.

Prevalence of reported violence

The cost estimates in this report have been calculated using a reported prevalence approach based on Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Personal Safety Survey (PSS) data.6a A prevalence approach measures the costs associated with domestic violence in a specific year, based on the number of women experiencing violence in that year – that is, it includes the costs of all domestic violence occurring in that year. The approach captures reported violence only – in other words, unreported violence is not included.

Implementation of the Plan of Action would likely result in increased awareness of domestic violence against women and their children, leading to an initial increase in the number of cases of reported violence (and an associated increase in costs). However, a reduction in the levels of violence to 2021 is expected as the initiatives gain traction. Without appropriate action, the prevalence of reported violence is assumed to increase on average at a rate consistent with forecast population growth to 2021-22.

Key findings

The cost of violence

Table 1 below summarises the costs of domestic (intimate partner) and non-domestic (non-intimate partner) violence against women and their children by category in 2021-22 without appropriate action.

| Category of cost | Cost ($ million) |

Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Pain, suffering and premature mortality | 7,530 | 48 |

| Health | 863 | 5 |

| Production-related | 1,181 | 8 |

| Consumption-related | 3,542 | 23 |

| Administrative and other | 1,077 | 7 |

| Second generation | 280 | 2 |

| Transfer costs | 1,104 | 7 |

| Total7 | 15,577 | 100 |

| Total (excluding pain, suffering and premature mortality) | 8,048 | 100 |

Without appropriate action, the total cost of violence against women and their children in 2021 22 is estimated to be $15.6 billion. The largest contributor is ‘pain, suffering and premature mortality’, at $7.5 billion. The remaining costs total $8.1 billion. The largest part is ‘consumption-related’ costs at $3.5 billion. The next largest categories are ‘production’ and ‘administrative and other’, at $1.2 billion and $1.1 billion respectively.

Table 2 shows which groups in society bear these costs.

| Affected group | Cost ($ million) |

Proportion of total (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Victim/survivor | 8,127 | 52 |

| Federal, state and territory governments | 2,945 | 19 |

| Community | 1,908 | 12 |

| Children | 1,274 | 8 |

| Perpetrator | 855 | 6 |

| Employers | 456 | 3 |

| Friends and family | 12 | 0.1 |

| Total | 15,577 | 100 |

Reflecting the large contribution of pain, suffering and premature mortality to total costs, the largest cost burden ($8.1 billion) is estimated to be borne by victims/survivors of violence. The next largest burdens are on the federal and state/territory governments ($2.9 billion) and the general community ($1.9 billion).

Vulnerable groups

The ways in which women and their children experience violence, the options open to them in dealing with violence, and the extent to which they have access to services that meet their needs are shaped by the intersection of gender with factors such as disability, English language fluency, ethnicity, physical location, sexuality, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status, and migration experience8. These factors act to increase vulnerability to the risk and effects of violence.

The estimated cost of violence perpetrated against women from selected vulnerable groups is presented in Table 3.

| 2021-22 ($ million) |

|

|---|---|

| Immigrant and refugee women | 4,050 |

| Women with disabilities | 3,894 |

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women | 2,161 |

| Children who witness violence | 1,554 |

Without appropriate action to 2021-22, violence against immigrant and refugee women is estimated to cost the economy just over $4 billion; against women with disabilities $3.9 billion; against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women $2.2 billion; and in relation to children who witness violence $1.5 billion.

Next steps

Violence against women and their children carries an enormous economic cost to society. The Plan of Action describes the commitment and actions needed to guide all Australians, their governments and communities in reducing this violence. A significant proportion of the costs associated with violence against women and their children to 2021-22 will be avoided with action to implement the Plan of Action initiatives. The costs of the initiatives and the anticipated cost-effectiveness of investment are areas that should be considered as part of a detailed business case for investment.

- Violence against women and their children includes domestic (intimate and ex-intimate partner) and non-domestic violence. Importantly (as with most studies in this field), the estimate captures reported violence only – in other words, unreported violence is not included.

- Violence against women and their children includes domestic and non-domestic violence.

- Includes domestic violence and non-domestic sexual assault and is comprised of $7.6 billion in non-financial costs (pain, suffering and premature death) and $8 billion in financial costs.

- 4. Australian Bureau of Statistics, Personal Safety Survey, ABS Cat. No. 4906.0, Canberra, 2005.

- Access Economics, The Cost of Domestic Violence to the Australian Economy: Part I and Access Economics, The Cost of Domestic Violence to the Australian Economy: Part II, 2004, viewed December 2008

- Note that the Access Economics estimate pertains to domestic violence only and includes domestic violence perpetrated against men. The estimates in this report include non-domestic sexual assault and exclude violence perpetrated against men.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, Personal Safety Survey, ABS Cat. No. 4906.0, Canberra, 2005.

- Totals hereafter may not sum because of rounding.

- Stubbs, Violence Against Women: the Challenge of Diversity for Law, Policy and Practice. Second National Outlook Symposium: Violence Crime, Property Crime and Public Policy, Australian Institute of Criminology Canberra, 1997.

1. Introduction

1.1 Background

Violence against women and their children remains a profound problem and addressing it is one of the greatest challenges for Australia. Around one in three Australian women experience physical violence and almost one in five women experience sexual violence over their lifetime9.

In May 2008, the Australian Government established the National Council to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children (the Council) to provide expert advice on measures to reduce the incidence and impact of sexual assault and domestic and family violence. The first task for the Council was to develop a national plan of action.

Time for Action: The National Council’s Plan for Australia to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children (the Plan of Action) sends a strong message to the Australian community that violence against women is not acceptable in any form. Its development has the support of a wide range of stakeholders and, most importantly, is built from the many voices of women

The Plan of Action describes the commitment and actions needed to guide all Australians, their governments and communities in reducing violence against women and their children. Implementation of the Plan of Action is central ’s four priorities for women:

- Reducing violence against women.

- Increasing women’s economic independence.

- Increasing the voice of women in the community.

- Working in partnership with men to achieve gender equality.

The Plan of Action includes strategies and initiatives that are focused around six key outcomes:

- Communities are safe and free from violence.

- Relationships are respectful.

- Services meet the needs of women and their children.

- Responses are just.

- Perpetrators stop their violence.

- Systems work together effectively.

The Plan of Action initiatives form a comprehensive suite of interventions to tackle the problem of violence against women and their children, both in terms of responding to violence and early intervention and prevention. Violence against women and their children carries an enormous economic cost to society. A significant proportion of these costs to 2021-22 can be expected to be avoided with the introduction of Plan of Action initiatives.

1.2 Objective

The objective of this report is to present an estimate of the financial and non financial costs associated with violence against women and their children in 2021 22 that may be anticipated if Australians, their governments and communities do not take action by implementing the Plan of Action initiatives. The estimated costs of violence against women and their children is then used to demonstrate the cost reductions that could be achieved with reductions in the levels of violence to 2021-22 as a result of implementing the initiatives.

1.3 Scope

Domestic interpersonal violence (as opposed to violence perpetrated by a stranger) has been the focus of most Australian studies. Australia was one of the first countries to attempt to calculate the economic costs of domestic violence. Despite the inadequacy of much of the necessary data, the Australian studies were traditionally more successful in calculating the direct costs of domestic violence (examples include the cost of crisis accommodation, legal services, income support, and health and medical services) than in calculating the indirect costs of domestic violence (examples include the replacement of lost or damaged household items, and costs associated with changing houses or schools)10.

For this study, KPMG has adopted as a starting point, work undertaken by Access Economics on behalf of the Office of the Status of Women in 200411. This work presented an estimate of the costs of domestic violence to the Australian economy, and may generally be regarded as the most recent comprehensive economy-wide estimate of the cost of domestic violence in Australia in 2002-03.

Key features of this methodology included:

- a focus on economic costs, and a clear distinction between economic costs and transfer payments;

- use of a prevalence approach that conceptually captures all annual costs of domestic violence and its consequences;

- allocation of costs to seven categories:

- pain, suffering and premature mortality;

- health costs;

- production-related costs;

- consumption-related costs;

- administrative and other costs;

- second generation costs;

- transfer costs.

- allocation of costs to eight groups which bear the costs and pay or receive transfer payments:

- victim/survivor;

- perpetrator;

- children;

- friends and family;

- employer;

- federal government;

- state/territory and local government;

- rest of the community/society (non-government).

This report updates the cost estimates in the Access Economics study and projects the costs to 2021-22 (with estimates presented in 2007-08 dollars). In updating the 2002-03 estimates, we have in some cases sought to use the most recent data as a basis for updating the costs, and in other cases we have used an appropriate escalation factor to update the costs (rather than replicating the construction of these costs), based on sources referenced in the Access Economics report.

The aim in adopting the Access Economics framework is to build on work already done in this area rather than necessarily recreating the estimate from scratch. The scope and effort implied by the Access Economics work far exceeds that of this study. It is therefore not KPMG's intention that the estimates in this report be considered the latest point of reference for researchers and analysts in this field.

Rather, the aim of this report is to provide indicative estimates of costs of violence against women and their children in 2021-22, and the reduction in costs that might be achieved with a reduction in levels of violence. It is the magnitude of the costs and possible reductions that can be achieved that are emphasised above the actual figures presented. Its purpose is to provide decision-makers with a sense of the scale of this problem and its impact on society, in order to provide another perspective on the need and benefits of intervention as advocated by the Plan of Action.

The caveats placed by Access Economics on the 2002-03 estimates still apply in that the overall findings must be considered indicative (and in some cases speculative) and are conditional on numerous assumptions made during the course of the analysis. A considerable margin of uncertainty surrounds the original estimate (and is retained in this update and forecasting of the estimates to 2021-22). Estimates are based on limited data and on parameters that reflect a large element of judgement12.

The project scope involved the following:

- The model was based on desktop analysis. Cost estimates are indicative only, and should be used for informing decisions rather than as a basis for decision-making.

- The Access Economics estimates formed the basis for updated 2007-08 estimates and were used as the basis for projecting costs to 2021-22. Costs are presented in 2007-08 dollars.

- Where sufficient information was not available, or time did not permit the reconstruction of the Access Economics cost estimates, assumptions were adopted based on the best available evidence.

- All assumptions and their bearings on the cost estimates are transparent.

- The analysis establishes a ‘base case’ profile which forecasts levels of violence against women and their children without intervention (that is, it assumes a continuation of current policy).

- The analysis adopts a reported prevalence-based approach.

- The economic costs do not include the cost of the Plan of Action initiatives. These costs would be estimated as part of a detailed business case for investment.

- The levels of reduction in violence cited in the report do not necessarily reflect the reduction in violence achievable with the implementation of the Plan of Action. This would form part of a detailed business case for investment.

1.4 Approach

The approach to this project involved these key steps:

- Constructing the base case ‘prevalence of violence’ profile

- The number of women and children experiencing violence in 2021-22 was calculated using prevalence rates from the Australian Bureau of Statistics Personal Safety Survey13. Extrapolations to 2021-22 are based on expected population changes for women and age. The total number of victims/survivors therefore takes into account varying population growth of each age category. This provides a baseline for growth in domestic violence up to 2021.

- Constructing the economic costs of violence. This involved:

- constructing and updating the 2002-03 cost estimates by obtaining relevant data to establish present-day costs on which the forecasting was based and applying appropriate cost escalation factors

- applying costs to the base case profile to estimate the economic costs of violence against women in 2021-22 if no action is taken

- deriving a cost per victim/survivor by dividing the total cost by the number of projected victims/survivors in each year.

- Calculating the cost impact. This involved:

- applying the cost per victim/survivor to estimate the costs that could be avoided for given reductions in reported violence.

1.5 Notes to the findings

The report presents estimates of the financial and non-financial costs and cost reduction impacts that may be achievable with broad implementation of the Plan of Action. Estimates are indicative only and are not linked to specific initiatives in the Plan. This report is not a submission for funding the Plan of Action. It does not contain views on the cost-effectiveness of specific initiatives proposed in the Plan. These are areas that should be considered as part of any business case for investment.

1.6 Structure of the report

The remainder of this report is structured as follows:

- Section 2 provides a definition of domestic violence that underpins the estimates in this report; outlines the classification of costs used in the report; and briefly summarises previous Australian and international studies on the costs of domestic violence and impact of intervention.

- Section 3 defines and outlines the prevalence of domestic violence in Australia.

- Sections 4 to 10 estimate the costs for each cost category (by cost sub-category and by affected group).

- Section 11 presents the effects of including the costs of non-intimate partner violence.

- Section 12 identifies the costs of violence against women and their children for selected vulnerable groups.

- Appendix provides details of cost breakdowns and the method used to calculate costs.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, Personal Safety Survey, ABS Cat. No. 4906.0, Canberra, 2005.

- Laing and Bobic, Economic costs of domestic violence, Australian Domestic and Family Violence Clearinghouse: Literature Review, p. 6, 2002, viewed December 2008.

- Access Economics, The Cost of Domestic Violence to the Australian Economy: Part I, 2004, viewed December 2008.

- Access Economics, The Cost of Domestic Violence to the Australian Economy: Part I, 2004, viewed December 2008, p. VI and VIII

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, Personal Safety Survey, ABS Cat. No. 4906.0, Canberra, 2005.

2. Analysis foundations

2.1 Definitions

The Plan of Action adopts the United Nations definition of violence against women and children as “… any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life14.”

Further information on the type and nature of violence against women and their children encompassed by the Plan of Action are contained in the Plan and include both domestic (intimate partner) and family violence as well as sexual assault perpetrated by a stranger.

The Access Economics work considered domestic violence only. The cost estimates in this report attempt to capture the costs associated with the more encompassing definition of violence against women and their children envisaged by the Plan of Action. This requires making a distinction between intimate partner and non-intimate partner violence.

The impact of violence against women and their children where the violence is perpetrated by a non-intimate partner presents different costs than for domestic violence. For example, violence perpetrated by a stranger is less likely to occur in the victim/survivor’s home and so in these instances the cost of replacing broken and damaged household possessions is not generally incurred by the victim/survivor. Moreover, the children of the victim/survivor are less likely to witness the violence.

KPMG has sought to include the costs of non-domestic violence by assuming that the costs of non-domestic violence are the same as for domestic violence, with the exception that non-domestic violence is less likely to occur in the victim/survivor’s home or be witnessed by their children. Second generation costs and consumption costs are therefore excluded from the non-domestic violence estimate. The Access Economics estimate also includes violence perpetrated against men, which is excluded from the KPMG estimate.

2.2 Classification of costs

2.2.1 Direct, indirect (and opportunity) costs

Most studies of this nature seek to estimate direct (or tangible) costs and indirect (or intangible) costs associated with violence. The terms direct or tangible are commonly used interchangeably to refer to the costs associated with the provision of a range of facilities, resources and services to a woman and her children as a result of her being subject to violence15. Examples are the costs of crisis services,accommodation services, legal services, income support, and health and medical services.

The terms indirect and intangible are also used interchangeably, and refer to the pain, fear and suffering incurred by women and children who live with violence. These costs are sometimes termed the indirect social and psychological costs of violence16. Examples include replacing damaged or lost household items, replacing school uniforms and equipment when children change schools, and settlement of a partner’s bad debts.

A third cost category of opportunity costs has also been adopted. Opportunity costs can be defined as the cost of opportunities which the victim/survivor has lost as a result of being in or leaving a violent relationship. An opportunity cost is the cost foregone when the woman’s options are limited by the circumstances in which she finds herself. Examples include the loss of employment and promotion opportunities and quality of life. Opportunity costs are often included as part of indirect costs.

We note that Access Economics in their 2004 study concluded that the distinction between direct and indirect costs was not necessarily useful, given the problems of definition and comparison17. The cost categories adopted in the 2004 study (and those adopted for this estimate) therefore combine all three types of costs into seven cost categories as shown in Table 4.

| Cost category | Types of costs included |

|---|---|

| Pain, suffering and premature mortality | Costs of pain and suffering attributable to violence. Costs of premature mortality measured by attributing a statistical value to years of life lost. |

| Health costs | Includes private and public health costs associated with treating the effects of violence on the victim/survivor, perpetrator and children. |

| Production-related costs | Includes costs associated with:

|

| Consumption-related costs | Includes costs associated with:

|

| Second generation costs | Includes private and public health costs associated with:

|

| Administrative and other costs | Includes private and public health costs associated with:

|

| Transfer costs | Includes ‘deadweight loss’ to the economy associated with:

|

The Access Economics report contains further commentary on cost classifications relevant to the method of cost estimation – including economic and non-economic costs, prevention and case costs, short-run and long-run costs, and transfer costs. This may aid in understanding and interpreting the cost estimates in this report.

2.3 Costs of violence and impact of intervention

2.3.1 Australia

Recent studies of the economic costs to Australia have estimated total national costs of domestic violence and other associated fields of study, including child abuse, crime and drug abuse19. The methodology used will naturally vary, depending on the field of study and area of research focus. However, the range highlights the varied coverage of some studies and the variable consideration of the linkages between costs incurred by one entity affecting and driving costs in other areas.

The 2004 Access Economics report classified the costs of domestic violence by seven cost categories, calculating the estimated cost in 2002-03 (see Table 5).

| Category | Annual cost, 2002-03 | |

|---|---|---|

| $ million | % of total | |

| Pain, suffering and premature mortality | 3,521 | 44 |

| Consumption-related | 2,575 | 32 |

| Production-related | 484 | 6 |

| Administrative and other | 480 | 6 |

| Transfers | 410 | 5 |

| Health | 388 | 5 |

| Second generation | 220 | 2 |

| Total | 8,078 | 100 |

‘Pain, suffering and premature mortality’ was by far the most costly category at $3.5 billion, contributing 44 per cent of the total cost of domestic violence. Health costs were $388 million.

The study estimated that the largest cost burden was borne by victims of domestic violence at $4.0 billion, followed by the rest of the community and society at $1.2 billion and the federal government at $848 million. Subsequent groups were children (9.5 per cent of total cost), perpetrators (6.9 per cent), state/territory and local governments (6 per cent), employers (2.2 per cent) and friends and family (0.1 per cent)21.

A breakdown of comparable expenditure of government by jurisdictions is unavailable. Using an updated Access Economics cost estimate to state/territory and local government of $554 million in 2007-08 and population data, in the absence of other data, an estimate of the spend in jurisdictions on domestic violence may be derived as shown in Table 622.

| Jurisdiction | Estimated expenditure ($ million) |

Proportion of total (%) |

|---|---|---|

| New South Wales | 180 | 33 |

| Victoria | 137 | 25 |

| Queensland | 111 | 20 |

| Western Australia | 56 | 10 |

| South Australia | 41 | 8 |

| Australian Capital Territory | 13 | 2 |

| Northern Territory | 9 | 2 |

| Total | 547 | 100 |

This methodology has obvious limitations and should be treated with caution. For example, the NSW Government spent an estimated $351 million in agency costs in 2007-08 as a result of domestic and family violence24, significantly higher than the NSW state expenditure estimate above25.

The total costs of domestic violence in NSW were estimated at $1.5 billion in 199026. The study in NSW found that women bear the greatest share of the economic costs of domestic violence. The federal government was found to bear the largest proportion of government costs, through expenditure on income support, housing and medical costs. State government costs were primarily incurred through the provision of court and legal services, child welfare and family support programs.

Using a ‘retrospective case study’ approach to women’s experience of domestic violence in Tasmanian and Northern Territory studies, the direct costs of domestic violence in Tasmania in 1994 were estimated at $17.6 million and $8.9 million in the Northern Territory in 1996. Indirect costs were also significant but were not extrapolated to gain a state/territory-wide estimate. The provision of income support comprised the greatest proportion of direct costs, followed by accommodation costs. The government/community sector bore the greatest share of direct costs, while women bore the greatest proportion of indirect costs27.

Other research focused on the qualitative and quantitative costs incurred by business and the corporate sector and attempted to estimate the annual cost of domestic violence to Australian employers28. This research highlighted the need for consideration of linkages. For example, the direct costs to employers are not only end-costs in themselves but also affect other aspects of an organisation, such as distribution and production, which can result in late deliveries, bringing about customer dissatisfaction and lost business. Similarly, costs to women, such as the inability to work caused by domestic violence, have a ‘domino-effect’ on other sectors of society: income forgone by victims/survivors results in diminished profits for business and decreased tax revenue to government.

2.3.2 International research

Research has also been undertaken internationally on the costs of domestic violence. In the United Kingdom, for example, Professor Walby of the University of Leeds estimated in 2004 the total cost of domestic violence for the state, employers and victims/survivors at around £23 billion a year29. As in Australia, the human and emotional cost borne by victims/survivors through pain and suffering makes up the largest component at over £17 billion. The other costs are broken down as follows:

- Lost economic output due to time off work – around £2.7 billion a year. It was estimated that around half of the cost is borne by employers and half by individuals in lost wages.

- Criminal justice system – around £1 billion a year (nearly one-quarter of the criminal justice system budget for violent crime). Includes police, prosecution, courts, probation, prison and legal aid.

- Health care – around £1.2 billion a year. Includes physical injuries and mental health care.

- Civil legal services – over £0.3 billion a year. Includes legal actions such as injunctions and divorce

- Social services – nearly £0.25 billion a year, overwhelmingly related to children

- Housing and refuges – £0.16 billion a year.

Professor Walby found the costs of domestic violence are partly borne by the state and the wider society, partly by the individual victims/survivors, and partly by employers. She allocated the burden at £2.9 billion a year for the state, around £19 billion a year for victims/survivors, and £1.3 billion a year for employers.

A New Zealand study indicated that the annual cost of family violence in that country was at least NZ$1.2 billion30. In 1993-94 this was more than the NZ$1 billion earned from wool exports; nearly as much as the NZ$1.4 billion spent on unemployment benefits; and around half the NZ$2.5 billion earned from forestry exports.

Both these international studies emphasise that the costs of domestic violence are just as significant abroad, in terms of both the economic costs borne by the state and society, and the costs borne by individual victims/survivors, relatives and businesses.

2.3.3 The impact of intervention

While a number of studies have sought to calculate the cost of domestic violence, there is little information which identifies and analyses the impacts of government intervention on the costs of domestic violence. Information that is available is primarily international.

During 2002, the European Union defined seven indicators which identify the extent and nature of partner violence within the member states. The indicators are being used as a surveillance and evaluation tool for implementation of measures and methods to reduce violence against women. Denmark is one of the first countries to publish such analysis.

Denmark has observed significant falls in some indicators of violence over a relatively short period: from 2000 to 2005, a 30 per cent decline in domestic violence was observed following the implementation of actions plans in 2002-2004 and 2005-2008 to stop violence against women31. However, this has been countered by an increase in overall violence statistics which still appear to be climbing, with little indication of when they will plateau; between 2000 and 2005, an approximate increase of 8 per cent was observed. This is not an altogether unexpected outcome, given that government intervention increases awareness and can have the effect of increasing reported violence.

In Norway, a government action plan on domestic violence was implemented in 2004. While the number of formal reports of domestic violence increased from 3,890 cases in 2003 to 4,348 cases in 2005, this was not attributed to an increase in violence but was seen rather as an indication that more women were contacting the police as a result of greater openness about the problem and less stigma associated with being a victim of violence in couples32.

In the United Kingdom, the Home Office (in partnership with the Prime Minister’s Delivery Unit) developed a National Domestic Violence Delivery Plan for 2005-06. A number of ‘proxy’ indicators against which the government intends to measure the medium- to long-term success of the strategy were identified and are yet to be fully measured against intervention, but provide an indication for trends in domestic violence at this point:

- Homicides as a result of domestic violence: On average in the UK, two women a week are killed by a partner or ex-partner33. Since 1997, trends in domestic violence homicides have been broadly level and although an upward trend can be detected in recent years, the numbers are too small to be statistically significant. In the medium to long term, a downward trend would be desired as agencies begin to focus more on early intervention and protection.

- Headline prevalence of domestic violence: Measured by the British Crime Survey Inter-Personal Violence module, which estimates the extent of domestic violence, sexual assault and stalking in England and Wales. The general trend remains the same, with between 18 and 25 per cent of violent crime being domestic violence-related.

- Numbers of a) young people and b) all people who think that violence is acceptable in some circumstances: Research from 1998 showed that one in five young men and one in 10 young women thought that violence towards a partner was acceptable in some situations34. While there is no information on trends, these figures will be used as the baseline to measure this indicator annually using the Office of National Statistics Survey. It is hoped levels of acceptance will reduce as levels of awareness increase.

- Percentage of domestic violence incidents with a power of arrest where an arrest was made related to the incident and, of this, the percentage of partner-on-partner violence: Since April 2004, this has been a Statutory Indicator in the Policing Performance Assessment Framework. The objective is that the underlying trend will be upwards, with increased training and guidance for frontline police officers.

- The number of domestic violence offenders brought to justice: This will measure outcomes in the criminal justice system. The number of offenders successfully prosecuted would hopefully increase, and the ratio of successful prosecutions to arrests would increase too, as evidence-gathering and support for victims improve.

- The number of civil orders made: In 2003, around 30,000 non-molestation and occupation orders were issued and about 4,500 undertakings were given.

- Actions against domestic violence: The average number of refuge places per 10,000 population was 0.5 in both 2001-02 and 2002-03 and 0.96 in 2003-0435.

- Victim satisfaction with the support they have received from key agencies: Data will be gathered from a sample of those who said they were victims in the British Crime Survey Inter-Personal Violence module and a pool of victims from refuges. It will be produced on the government’s behalf by Women’s Aid, as responses will need to be sensitive to the needs of victims.

All identified international models of costing interventions are as yet relatively undeveloped in their formulation and implementation, and more time is required to draw concrete conclusions as to what this would likely mean for costing impacts and timings of Australian measures. One clear theme is that most nations have a relatively ‘fluid’ approach to measuring outcomes for national strategies on reducing domestic violence.

An important component of the Plan of Action will be the establishment of key performance indicators linked to desired outcomes, so that progress in addressing this problem can effectively be monitored, measured and evaluated against anticipated outcomes identified in the business case for investment.

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, United Nations Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women, United Nations, 1993.

- KPMG Management Consulting, Economic Costs of Domestic Violence in Tasmania, Tasmanian Domestic Violence Advisory Committee, Office of the Status of Women, Hobart, 1994. Cited in Laing, Australian Studies of the Economic Costs of Domestic Violence, Australian Domestic and Family Violence Clearinghouse Topics Paper, 2001, p. 2.

- Laurence and Spalter-Roth, Measuring the Costs of Domestic Violence Against Women and Cost Effectiveness of Interventions: An initial assessment and proposals for further research, Institute for Women's Policy Research, Washington, 1996. Cited in Laing, Australian Studies of the Economic Costs of Domestic Violence, Australian Domestic and Family Violence Clearinghouse Topics Paper, 2001, p. 2.

- Access Economics, The Cost of Domestic Violence to the Australian Economy: Part I and Access Economics, 2004, viewed December 2008, p. 3.

- Access Economics, The Cost of Domestic Violence to the Australian Economy: Part I, 2004, viewed December 2008, p. 5.

- Henderson, Impacts and Costs of Domestic Violence on the Australian Business/Corporate Sector, Brisbane Lord Mayor’s Women’s Advisory Committee, Brisbane City Council, 2000; Keatsdale, The Cost of Child Abuse and Neglect in Australia, Keatsdale Pty Ltd Management Consultants for the Kids First Foundation 2003; Mayhew, Counting the Costs of Crime in Australia, Australian Institute of Criminology, Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice No. 247, 2003; Collins and Lapsley, Counting the Cost: Estimates of the social costs of drug abuse in Australia in 1998-9, National Drug Strategy, Monograph Series No. 49, 2002.

- Access Economics, The Cost of Domestic Violence to the Australian Economy: Part I and Access Economics, 2004, viewed December 2008

- Access Economics, The Cost of Domestic Violence to the Australian Economy: Part I, 2004, viewed December 2008

- Updated from 2003-04 to 2007-08 dollars using CPI index from Australian Bureau of Statistics, Consumer Price Index, Australia, September 2008, ABS Cat. No. 6401.0, Canberra, 2008.

- The Access Economics estimate is broken down proportionately by population in each jurisdiction to estimate the possible expenditure on domestic violence by governments in each jurisdiction.

- The National Council to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children, Background Paper to Time for Action: The National Council’s Plan for Australia to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2009-2021, Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, Commonwealth of Australia, 2009. Figure is for 2003-04 updated to 2007-08 dollars using consumer price index (CPI) change between 2004-05 and 2007-08 from Australian Bureau of Statistics, Consumer Price Index, Australia, September 2008, ABS Cat. No. 6401.0, Canberra, 2008, Tables 1 and 2, CPI: All Groups, Index Numbers and Percentage Changes.

- 2ARTD Consultants Pty Ltd, Coordinating NSW Government Action against Domestic and Family Violence: Final Report, Department of Premier and Cabinet, NSW Government, Sydney, 2007, viewed November 2008

- Distaff Associates, Costs of Domestic Violence (Report 073058770), Women's Co-ordination Unit, Sydney, 1991. Cited in: Laing and Bobic, Economic costs of domestic violence, Australian Domestic and Family Violence Clearinghouse: Literature Review, viewed December 2008, pp 6. While the estimate is out-dated, KPMG is unaware of more recent comparable state expenditure data.

- KPMG Management Consulting, Economic Costs of Domestic Violence in Tasmania, Tasmanian Domestic Violence Advisory Committee, Office of the Status of Women, Hobart, 1994. Cited in Laing, Australian Studies of the Economic Costs of Domestic Violence, Australian Domestic and Family Violence Clearinghouse Topics Paper, 2001, p. 5.

- Henderson, Impacts and Costs of Domestic Violence on the Australian Business/Corporate Sector. Brisbane Lord Mayor’s Women’s Advisory Committee, Brisbane City Council, 2000. Cited in Laing, Australian Studies of the Economic Costs of Domestic Violence, Australian Domestic and Family Violence Clearinghouse Topics Paper, 2001, p. 8.

- Walby, The Cost of Domestic Violence, Women and Equality Unit Research Summary, 2004, viewed December 2008

- 30. Snively, ‘The New Zealand Economic Cost of Family Violence’, Social Policy Journal of New Zealand (4), 1995. Cited in: Laing and Bobic, Economic costs of domestic violence, Australian Domestic and Family Violence Clearinghouse: Literature Review, 2002, viewed December 2008, p. 7.

- National Institute of Public Health Denmark, Men’s violence against women: Extent, characteristics and the measures against violence 2007, English summary, 2008.

- United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, List of issues and questions with regard to the consideration of periodic reports: Norway, Pre-session working group, Thirty-ninth session, 2007.

- 33. United Kingdom Home Office, Crime in England and Wales 2001/02 – Supplementary Volume and Crime in England and Wales 2002/03, United Kingdom Government Home Office, 2003.

- Mullender, Young People’s Attitudes Towards Violence, Sex and Relationships: A Survey and Focus Group Study, Zero Tolerance Charitable Trust, 1998.

- United Kingdom Government, Domestic Violence: A National Report, 2005.

3. Prevalence of reported violence

3.1 Prevalence of violence

The costs of a particular condition in a given year can be estimated using a prevalence approach or an incidence approach. The difference between the approaches relates to how they each capture the occurrence of the condition, which in this case is violence against women and their children.

- A prevalence approach measures the costs associated with domestic violence in a specific year, based on the number of women experiencing violence in that year. That is, it includes the costs of all domestic violence occurring in that year.

- An incidence approach measures the lifetime costs (net present value of current and future costs) associated with domestic violence in a given year, based on the number of new cases of violence in that year. That is, it includes the costs of domestic violence occurring in that year for the first time.

While an incidence approach is “… useful for modelling the progress of a disease and its costs over time, it is less useful in the case of domestic violence which has no typical pattern, either of the nature of the abuse or in the types and frequency of services used36.”

The cost estimates in this report have been calculated using a reported prevalence approach based on Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Personal Safety Survey (PSS) data36a. Importantly (as with most studies in this field), the approach captures reported violence only – in other words, unreported violence is not included.

3.2 Women experiencing violence

Based on population estimates in Australia, Table 7 shows the estimated number of women who will report violence in 2021-22 if no action is taken.

| 2021-22 | |

|---|---|

| Physical assault | 194,817 |

| Sexual assault | 31,061 |

| Sexual threat | 44,069 |

| Stalking | 8,322 |

| Emotional abuse | 212,824 |

| Total victims/survivors (domestic) | 385,426 |

| Total victims/survivors (non-domestic) | 362,057 |

| Total victims/survivors38 | 747,483 |

The estimated number of women who will experience and report domestic violence in 2021-22 is 385,426. Most of this will be in the form of emotional abuse (55 per cent) followed by physical assault (51 per cent). A further 362,057 women will experience non-domestic violence (available data prevents the same breakdown by type of violence as for domestic violence). Without appropriate action, some 747,483 women will experience and report violence in 2021-22.

3.3 The costs of violence

The following sections detail the costs of violence based on the prevalence of reported violence shown above to 2021-22. The sections provide details for each of the seven major cost categories and show the impact in terms the cost sub-categories and who bears the cost.

All figures relate to domestic violence, unless otherwise indicated. In many cases, the available data prevents us from breaking down the costs of non-domestic violence to the same level of detail that is possible for domestic violence. Section 11 presents the effects of including the costs of non-intimate partner violence on total costs of violence.

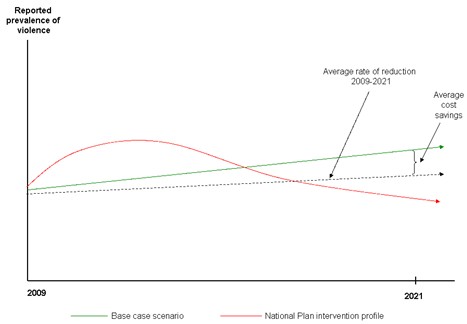

We note that with the implementation of the Plan of Action and increased awareness of the costs of domestic violence against women and their children, there is likely to be an initial increase in the number of cases of reported violence (and an associated increase in costs). However, a reduction in levels of violence over time can be expected as the initiatives gain traction. This pattern of prevalence in reported violence is presented for illustrative purposes only in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Profile of women experiencing violence (for illustrative purposes only)

The expected number of women experiencing violence if no action is taken is represented by the green profile. The number of women experiencing violence if the Plan of Action is implemented is represented by the red profile. The red profile reflects the anticipated increase in reporting of violence initially, followed by reduced levels of violence over time as the initiatives take effect.

The gap between the two profiles represents the additional cost or saving (depending on the particular year). The average savings are represented by the average of the difference between the green and red profiles over the total period. The avoided costs referred to in this report are the costs associated with victims/survivors’ experience of violence that are avoided, regardless of changes in aggregate levels of reported violence (which could be increasing or decreasing at the time of prevention).

Violence against women and their children will cost the Australian economy an estimated $13.6 billion in 2008-0939. The Plan of Action sets out an action agenda until 2021. This timeframe recognises the need for long-term investment and commitment in order to achieve long-term and sustainable change. The following sections present the estimated costs of violence against women and their children that can be anticipated to 2021-22 without appropriate action to address this problem.

Note that the following sections 4-10 present the costs relating to domestic violence only and differ from the costs presented in the overview. Section 11 provides information on how the costs of non-domestic violence are incorporated into the overall cost estimate.

- Laurence and Spalter-Roth, Measuring the Costs of Domestic Violence Against Women and Cost Effectiveness of Interventions: An initial assessment and proposals for further research, Institute for Women's Policy Research, Washington, 1996, cited in Laing, Australian Studies of the Economic Costs of Domestic Violence, Australian Domestic and Family Violence Clearinghouse Topics Paper, 2001, p. 17.

36a. Australian Bureau of Statistics, Personal Safety Survey, ABS Cat. No. 4906.0, Canberra, 2005. - 37. The number of victims/survivors in 2021-22 is estimated by applying the rate of growth in prevalence between 1996 and 2005 obtained from the Personal Safety Survey data to the number of victims presented in the Access Economics report. The number of perpetrators and children who witness domestic violence is derived from the number of victims/survivors.

- Australian research indicates that most violence against women is by way of sexual assault and domestic and family violence, most of which is perpetrated by intimate partners and in the home. This is not reflected in the estimates in this report which indicate that domestic violence represents just over half of total violence. This is possibly due to definitional issues: for example stalking, harassment and emotional abuse represent a significant proportion of violence but are not always included in definitions of violence.

- Violence against women and their children includes domestic (intimate and ex-intimate partner) and non-domestic violence.

4. Pain, suffering and premature mortality

4.1 Summary of findings

Table 8 summarises costs in 2021-22 for domestic violence against women and their children resulting from pain, suffering and premature mortality without intervention. Further details of the method for calculating cost estimates are in Appendix A.

| 2021-22 ($ million) |

|

|---|---|

| Total cost of pain, suffering and premature mortality | 3,883 |

Without the Plan of Action interventions, the cost of pain, suffering and premature mortality is estimated at $3.9 billion in 2021-22. For every woman whose experience of violence is prevented as a result of the Plan of Action intervention, $10,073 in pain, suffering and premature mortality costs can be avoided. This equates to $388 million in reduced costs if levels of violence could be reduced by just 10 per cent by 2021-22.

4.2 Category description

This category includes the less tangible costs of pain, suffering and premature death associated with domestic violence. The non-financial Disability Adjusted Life Year (DALY) approach41 is used to measure the years of life lost due to premature mortality and years of healthy life lost through pain and suffering. DALYs are then converted to a dollar figure by assigning a value to a statistical life year. Access Economics estimated the cost of pain, suffering and premature death was $3.5 billion in 2002-0342.

4.3 Cost and stakeholder breakdown

Table 9 summarises the cost of pain, suffering and premature death associated with victims/survivors of domestic violence.

| $ million | % of total | |

|---|---|---|

| Depression | 1,141 | 29 |

| Anxiety | 875 | 23 |

| Suicide | 475 | 12 |

| Alcohol | 380 | 10 |

| Tobacco | 376 | 10 |

| Drug use | 189 | 5 |

| Femicide | 156 | 4 |

| Physical injuries | 139 | 4 |

| Cervical cancer | 60 | 1 |

| Eating disorders | 51 | 1 |

| Sexually transmitted diseases | 22 | 1 |

| Total | 3,86444 | 100 |

Without appropriate action to address violence against women and their children, the cost of pain, suffering and premature death could reach over $3.8 billion in 2021-22. The main contributor to these costs (assuming no change in cost composition) is likely to be depression at 29 per cent of total costs, followed by anxiety at 23 per cent and suicide at 12 per cent.

Table 10 summarises who will bear the cost of pain, suffering and premature death associated with domestic violence.

| $ million | % of total | |

|---|---|---|

| Victim/survivor | 3,668 | 94.4 |

| Children | 211 | 5.4 |

| Perpetrator | 4 | 0.2 |

| Total45 | 3,88346 | 100 |

Without appropriate action to address violence against women and their children, the cost of pain, suffering and premature death in 2021-22 will be borne primarily by the victims/survivors at almost $3.7 billion (94 per cent). Children will also bear considerable costs of $211 million (5 per cent), followed by perpetrators at $4 million (0.2 per cent).

4.4 Plan of Action priorities

The Plan of Action advocates a range of actions designed to reduce the costs of pain, suffering and premature death as a result of violence against women. For example, the Plan of Action advocates the establishment of homicide/fatality review processes in each jurisdiction to review deaths that result from violence against women and their children.

If the review processes were established and review findings incorporated into ways of addressing violence against women and their children, $10,073 could be saved in costs associated with pain, suffering and premature death for every woman whose experience of violence is prevented.

- All figures are in 2007-08 dollars.

- The DALY approach was developed by the World Health Organisation, World Bank and Harvard University. Further information on the methodology.

- Access Economics, The Cost of Domestic Violence to the Australian Economy: Part I and Access Economics, The Cost of Domestic Violence to the Australian Economy: Part II, 2004, viewed December 2008. p. 30.

- All figures are in 2007-08 dollars.

- This figure excludes health and productivity costs which are captured in other cost categories.

- All figures are in 2007-08 dollars.

- Totals for victims, perpetrators and children are net of respective costs associated with health and productivity.

5. Health costs

5.1 Summary of findings

Table 11 summarises health costs in 2021-22 resulting from domestic violence

| 2021-22 ($ million) |

|

|---|---|

| Total health costs | 445 |

Without the Plan of Action interventions, the costs of health-related expenditure are estimated at $445 million in 2021-22. For every woman whose experience of violence is prevented as a result of the Plan of Action, $1,154 in health costs can be avoided. This equates to $45 million in reduced costs if levels

Category description

This category includes public and private health system costs associated with treating the effects of domestic violence, such as physical injuries, depression, anxiety, alcohol abuse and smoking. Access Economics estimated total health costs for female victims/survivors, perpetrators of violence 48.

Cost and stakeholder breakdown

Without appropriate action to address violence against women and their children,

Table 12 summarises who will bear the cost of suffering associated with domestic

| $ million | % of total | |

|---|---|---|

| Federal and state/territory governments | 305 | 68 |

| Victim/survivor | 87 | 20 |

| Community/society | 51 | 11 |

| Perpetrator | 2 | 1 |

| Total | 445 | 100 |

Without appropriate action to address violence against women and their children, health costs in 2021-22 will be borne primarily by federal and state/territory governments at $305 million (68 per cent). Victims/survivors will also bear

5.4 Plan of Action priorities

The Plan of Action advocates a range of actions that are designed to reduce

- The development and implementation of model codes of practice to ensure that there is consistency, transparency and accountability between sectors (health, community, legal) in delivering services that respond to sexual assault, domestic and family violence.

- The establishment of a professional national telephone and online crisis support service for anyone in Australia who has experienced, or is at risk of, sexual assault and/or domestic and family violence. The service should integrate and coordinate with existing services in all states and territories, offer professional counselling, provide information and referrals, use best practice technology, link with other 1800 numbers, have direct links with relevant local and state services, and provide professional supervision and advice to staff in services in isolated and remote areas.

- Develop a national evaluation approach to assess the effectiveness of service responses to women and their children who have experienced violence, including women with disabilities, living in a range of settings.

- To undertake research to better understand the range of responses needed by women who have experienced sexual assault and/or domestic and family violence, including women with disabilities living in a range of settings.

- All figures are in 2007-08 dollars.

- Access Economics, The Cost of Domestic Violence to the Australian Economy: Part I and Access Economics, The Cost of Domestic Violence to the Australian Economy: Part II, 2004, viewed December 2008, p. 34.

- All figures are in 2007-08 dollars.

6. Production-related costs

6.1 Summary of findings

Table 13 summarises production-related costs in 2021-22 resulting from domestic violence against women and their children.

| 2021-22 ($ million) |

|

|---|---|

| Total production-related costs | 609 |

Without the Plan of Action interventions, production-related costs are estimated at $609 million in 2021-22. For every woman whose experience of violence is prevented as a result of the Plan of Action intervention in a particular year, $1,581 in production-related costs can be avoided. This equates to $61 million in reduced costs if levels of violence could be reduced by just 10 per cent

6.2 Category description

This category includes the costs of short- and long-term productivity losses associated with domestic violence. Short-term productivity losses include temporary absenteeism from paid and unpaid work and employer administrative costs, while long-term losses reflect a permanent loss of the worker (homicide and premature death). Access Economics estimated the total cost of lost productivity 51.

6.3 Cost and stakeholder breakdown

Without appropriate action to address violence against women and their children, production-related costs could reach $609 million in 2021-22. The main contributor to these costs is likely to be costs relating to homicide and premature death at 30 per cent of total costs, followed by victims/survivors’ absenteeism

Table 14 summarises who will bear the production-related associated with

| $ million | % of total | |

|---|---|---|

| Employers | 235 | 39 |

| Community/society | 172 | 28 |

| Victim/survivor | 112 | 18 |

| Perpetrator | 90 | 15 |

| Total | 609 | 100 |

Without appropriate action to address violence against women and their children, production-related costs in 2021-22 will be borne primarily by employers at $235 million (39 per cent). The community will also bear considerable costs of $172 million (28 per cent) followed by victims/survivors at $112 million

6.4 Plan of Action priorities

The Plan of Action advocates a range of actions designed to reduce production related costs associated with violence against women, for example, by ensuring that the Government’s response to the Commonwealth Parliament’s Gender Pay Equity Inquiry addresses the links with violence against women. This will be achieved by Women’s Ministers, nationally, make representation to the Gender Pay Equity Inquiry and the Pensions Review, asking that the interrelationship between violence against women, lack of economic independence and gender inequality be considered as part of their reviews, and addressed

- All figures are in 2007-08 dollars.

- Access Economics, The Cost of Domestic Violence to the Australian Economy: Part I and Access Economics, The Cost of Domestic Violence to the Australian Economy: Part II, 2004, viewed December 2008, p. 43.

- All figures are in 2007-08 dollars.

7. Consumption-related costs

7.1 Summary of findings

Table 15 summarises consumption-related costs in 2021-22 resulting from domestic violence against women and their children.

| 2021-22 ($ million) |

|

|---|---|

| Total consumption-related costs | 3,542 |

Without the Plan of Action interventions, consumption-related costs are estimated at $3.5 billion in 2021-22. For every woman whose experience of violence is prevented as a result of the Plan of Action, $9,190 in consumption-related costs can be avoided. This equates to $354 million in reduced costs if levels of violence could be reduced by just 10 per cent by 2021-22.

7.2 Category description

This category includes short-term costs of replacing damaged property and defaulting on a bad debt, and the long-term cost arising from the loss of economies of scale in consumption (owing to reduced average household size). Access Economics estimated total consumption-related costs were $2.6 billion in 2002-0354.

7.3 Cost and stakeholder breakdown

Table 16 summarises consumption-related costs associated with domestic violence.

| $ million | % of total | |

|---|---|---|

| Economies of scale in consumption | 3,340 | 94 |

| Damaged/destroyed property | 202 | 6 |

| Total | 3,542 | 100 |

Without appropriate action to address violence against women and their children, consumption-related costs could reach $3.5 billion in 2021-22. The main contributor to these costs is likely to be the change in economies of scale at 94 per cent of the total costs. Consumption-related costs are assumed to be borne entirely by the victim/survivor and family and friends.

7.4 Plan of Action priorities

The Plan of Action advocates a range of actions that will particularly impact on consumption related costs:

- strengthen media and internet standards to address sexualised and denigrating representations of women, and minimise the impact of the persistent exposure to representations of violence in childhood and adolescence.

- developing, trialling, implementing and evaluating educational programs in a range of settings, based on best practice principles, for pre-schoolers, children, adolescents and adults that encourage respectful relationships and protective behaviours.

- building on and targeting existing resources, programs and services to help parents and primary caregivers provide positive parenting by supporting their children to develop respectful relationships.

- increasing the availability, range and evaluation of perpetrator programs that meet standard principles, particularly in rural and remote areas.

- All figures are in 2007-08 dollars.

- Access Economics, The Cost of Domestic Violence to the Australian Economy: Part I and Access Economics, The Cost of Domestic Violence to the Australian Economy: Part II, 2004, viewed December 2008, p. 46.

- All figures are in 2007-08 dollars.

8. Administrative and other costs

8.1 Summary of findings

Table 17 summarises administrative and other costs in 2021-22 resulting from domestic violence against women and their children.

| 2021-22 ($ million) |

|

|---|---|

| Total administrative and other costs | 555 |

Without the Plan of Action interventions, administrative and other costs are estimated at $555 million in 2021-22. For every woman whose experience of violence is prevented as a result of the Plan of Action, $1,441 in administrative and other costs can be avoided. This equates to $56 million in reduced costs if levels of violence could be reduced by just 10 per cent by 2021-22.

8.2 Category description

This category includes legal system costs (such as incarceration, court system and private legal costs), temporary accommodation costs, and other costs (such as counselling, perpetrator programs, and imputed carer costs). Access Economics estimated total administrative and other costs were $480 million in 2002-0357.

8.3 Cost and stakeholder breakdown

Without appropriate action to address violence against women and their children, administrative and other costs could reach $555 million in 2021-22. The main contributions to these costs are likely to be legal system costs at 58 per cent of total costs, followed by other administrative costs (counselling, perpetrator programs etc) at 22 per cent, and temporary accommodation at 20 per cent.

Without appropriate action to address violence against women and their children, administrative and other costs in 2021-22 will be borne primarily by government at $500 million (90 per cent) and the community at $46 million (8 per cent of the total costs).

8.4 Plan of Action priorities

The Plan of Action advocates a range of initiatives which will have a particular impact on administrative costs. These include:

- establishing a reference for the Australian Law Reform Commission to examine present state/territory domestic and family violence and child protection legislation and federal family law, and propose solutions to ensure that these laws work together to protect women and their children from violence.

- establishing a mechanism to enable the automatic national registration of domestic and family violence protection orders and subsequent variations, adaptations and modifications occurring anywhere in Australia or New Zealand.

- establishing or build on emerging homicide/fatality review processes in all states and territories to review deaths that result from domestic and family violence so as to identify factors leading to these deaths, improve system responses and respond to service gaps.

- commissioning the production of a model Bench Book, in consultation with jurisdictions and as part of a national professional development program for judicial officers on sexual assault and domestic and family violence.

- continuing to trial and evaluate supplementary legal processes in the area of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander family violence and sexual assault, such as restorative justice, which are driven by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

- All figures are in 2007-08 dollars.

- Access Economics, The Cost of Domestic Violence to the Australian Economy: Part I and Access Economics, The Cost of Domestic Violence to the Australian Economy: Part II, 2004, viewed December 2008, p. 54 and 57-58.

9. Second generation costs

9.1 Summary of Findings

Table 18 summarises second generation costs in 2021-22 resulting from domestic violence against women and their children.

| 2021-22 ($ million) |

|

|---|---|

| Total second generation costs | 280 |

Without the Plan of Action interventions, second generation costs are estimated at $280 million in 2021-22. For every woman whose experience of violence is prevented as a result of the Plan of Action, $725 in second generation costs can be avoided. This equates to $28 million in reduced costs if levels of violence could be reduced by just 10 per cent by 2021-22.

9.2 Category description

This category includes short-term costs of providing protection and other services (such as child protection services, childcare and remedial/special education) to children of relationships where there is domestic violence, and longer-term costs imposed on society by these children as they grow older (such as increased crime and future use of government services). Access Economics estimated total second generation costs were $220 million in 2002-0359.

9.3 Cost and stakeholder breakdown

Table 19 summarises second generation costs associated with domestic violence.

| $ million | % of total | |

|---|---|---|

| Increased adult crime | 107 | 38 |

| Increased juvenile crime | 53 | 19 |

| Childcare | 50 | 18 |

| Out-of-home care | 39 | 14 |

| Child protection | 21 | 8 |

| Changing schools | 9 | 3 |

| Special/remedial education | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 280 | 100 |

Without appropriate action to address violence against women and their children, second generation costs could be $280 million in 2021-22. The main contributor to these costs is likely to be the increase in crime committed as adults by children who witness violence, at 38 per cent of total costs, followed by the increase in juvenile crime at 19 per cent.

Without appropriate action to address violence against women and their children, second generation costs in 2021-22 will be borne primarily by government.

9.4 Plan of Action priorities

The Plan of Action advocates more help for parents and primary caregivers to provide positive parenting by supporting their children to develop respectful relationships. If this initiative were implemented, $725 could be saved in second generation costs for every woman whose experience of violence was prevented.

- All figures are in 2007-08 dollars.

- 59. Access Economics, The Cost of Domestic Violence to the Australian Economy: Part I and Access Economics, The Cost of Domestic Violence to the Australian Economy: Part II, 2004, viewed December 2008, p. 47.

- All figures are in 2007-08 dollars.

10. Transfer costs

10.1 Summary of findings

Table 20 summarises transfer costs in 2021-22 resulting from domestic violence against women and their children.

| 2021-22 ($ million) |

|

|---|---|

| Total transfer costs | 569 |

Without the Plan of Action interventions, transfer costs are estimated at $569 million in 2021-22.

10.2 Category description

Transfer payments such as government benefits and taxes represent a shift in payments from one group in society to another. They do not therefore represent a net cost to society and are not included in the analysis62. However, the taxes by their very nature, create distortions and inefficiencies in the economy which do impose a cost.

Violence against women and their children results in reduced tax revenue and a requirement to collect extra tax dollars including for:

- loss of income tax of victims/survivors, perpetrators and employers;

- additional induced social welfare payments;

- victim/survivor compensation payments and other government services.

The collection of these additional tax dollars creates the distortion or inefficiency in the economy. The cost of this inefficiency is often called the ‘deadweight loss’ or ‘excess tax burden’, which is a net loss to society.

Deadweight loss occurs when the loss to consumers and producers caused by the tax (i.e. the amount of a good or service that would have been consumed or produced, but for the tax) exceeds the revenue obtained from the tax. Access Economics estimated the total cost of transfers was $410 million in 2002-0363.

10.3 Stakeholder breakdown

The distortions and inefficiencies to the economy that result from transfers and the cost of raising additional taxation to cover this loss are borne almost entirely by government.

- All figures are in 2007-08 dollars.

- However, transfer payments are relevant in any distributional analysis of costs and benefits.

- 63. Access Economics, The Cost of Domestic Violence to the Australian Economy: Part I and Access Economics, The Cost of Domestic Violence to the Australian Economy: Part II, 2004, viewed December 2008, p. 60.

11. Non-domestic violence

11.1 Introduction

The Access Economics work considered domestic violence only. The cost estimates in this report attempt to capture the costs associated with the more encompassing definition of violence against women and their children envisaged by the Plan of Action. This requires making a distinction between intimate partner and non-intimate partner violence.

The cost estimates in sections 4 to 10 of this report refer to the cost of domestic violence only. These costs do not include the costs of non-domestic violence, or violence perpetrated by a stranger. This is because the available data prevents a breakdown of the costs of non-domestic violence to the same level of detail as is possible for domestic violence. However, excluding non-domestic violence significantly understates the total cost of violence against women and children.

This section presents the effects of including the costs of non-domestic partner violence on total costs of violence.

11.2 The cost of non-domestic violence

The impact of violence against women and their children where the violence is perpetrated by a non-intimate partner presents different costs than for domestic violence. KPMG has sought to cost non-domestic violence by excluding irrelevant cost categories.

For example, violence perpetrated by a stranger is less likely to occur in the victim/survivor’s home, so the cost of replacing broken and damaged household possessions is generally not an issue. The children of the victim/survivor are also less likely to witness non-domestic violence. The relevant cost categories excluded from non-domestic violence are therefore ‘second generation costs’ and ‘consumption costs’ (see Appendix A for further details).

In order to estimate a total cost to the economy, the $5.7 billion cost of non-intimate partner related violence is allocated proportionally across each relevant cost category. The breakdown of cost by category is presented in Table 21.

| Category of cost | Domestic violence costs ($ million) |

Non- domestic violence costs ($ million) |

Total cost ($ million) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain, suffering and premature mortality | 3,883 | 3,647 | 7,530 |

| Consumption-related | 3,542 | 0 | 3,542 |

| Production-related | 609 | 572 | 1,181 |

| Transfer costs | 569 | 535 | 1,104 |

| Administrative and other | 555 | 522 | 1,077 |

| Health | 445 | 418 | 863 |

| Second generation | 280 | 0 | 280 |

| Total | 9,883 | 5,694 | 15,577 |