SFCS National Evaluation Baseline Report on Communities for Children Process Evaluation

Attachments

Baseline Report on Communities for Children Process Evaluation

- List of tables

- Executive Summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Demographic profiles

- 3. Service mapping

- 4. Service coordination study

- 5. Fieldwork - service coordination study and partnership model study

- 6. Discussion

- References

- Appendices

List of tables

Table 1: National evaluation components

Table 2: Summary profile of CfC sites

Table 3: CfC sites by SEIFA Index of Disadvantage rankings, Statistical Local Areas, 2001

Table 4: Revised Service Mapping Typology sent to FPs

Table 5: Baseline Service Mapping for selected sites by Service Category

Table 6: Snapshot questionnaire: domains and indicators

Table 7: Respondents' position within their organisation

Table 8: Full-time equivalent staff employed by agencies in the LGA/CfC site

Table 10: Respondents' knowledge of CfC

Table 11: Agency's role in relation to CfC

Table 12: Proportion of services devoted to 0-5 year olds and their families by Agency Role in CfC

Table 14: Use of SFCS Outcomes Framework data by agency role in CfC

Table 15: Interagency involvement in various activities, and helpfulness score

Table 16: Level of involvement in interagency arrangements

Table 19: Perceived accuracy of statements describing circumstances in communities

Table 20: Awareness of services for 0-5 year olds and their families

Table 21: Pre-CfC interagency groups or committees designed to meet the needs of children aged 0-5

Table 22: Helpfulness of pre-CfC interagency groups or committees

Table 24: Current working relationship with other services

Table 25: Providing services in partnership with other agencies

Table 26: Helpfulness of providing services in partnership with other agencies

Table 28: Day-to-day Co-ordination - Score/Colour Code

Table 29: Effective Partnerships - Score/Colour Code

Table 30: Day-to-day Co-ordination - Site Mean Comparison

Table 31: Effective Partnerships - Site Mean Comparison

Table 32: Day-to-day Co-ordination - SFIA/Non-SFIA Group Comparison (Percentages)

Table 33: Effective Partnerships - SFIA/Non-SFIA Group Comparison (Percentages)

Table 34: Number of interviews by CfC site

Table 35: Number of interviews by contact type

Executive summary

This report contains a description of the methods and baseline results of the process evaluation of the Communities for Children (CfC) program, which is part of the Stronger Families and Communities Strategy (SFCS). The process evaluation reported here represents a subset of the National Evaluation of the SFCS and includes information from:

- Demographic profiles

- Service mapping

- Service coordination survey

- Field work relating to partnership model and service coordination.

Demographic profiles

A demographic profile of each community was compiled using data from the Census of Population and Housing, 2001. The key purpose was to provide contextual information about the social and economic characteristics of CfC sites, and the demographic characteristics of children aged five and under and their families. This provides a backdrop that helps to understand the different contexts in which CfC has been implemented.

Populations in CfC sites were more disadvantaged than the Australian population on most relevant indicators. CfC sites had higher proportions of children aged 0-5 years who lived in lone parent households than the national average, higher proportions with a parent unemployed, and higher proportions who lived in low-income families. Families with children aged 0-5 years in CfC areas were also more culturally diverse. Although the same proportion of the overall population was born outside the main English speaking countries in Australia and in CfC sites, there were higher proportions of children in CfC sites with mothers who did not speak English very well. CfC sites also had higher proportions of children who were of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Island descent, compared with Australia as a whole. Populations in CfC areas were also less likely to have attained Year 12 or equivalent levels of qualifications.

Service mapping

In the CFC sites at the commencement of the initiative, education services were the most prevalent services for children aged 0-5 years and their families (39%), followed by general child and family services (23%) and health services (20%). An additional 12% of services targeted population groups with a high risk of disadvantage. Nearly all FPs reported the existence of relevant networks in their site.

There was substantial variety in the number and type of services and networks available in each site. Overall, the number of services in the sites ranged from 39 to 227. Looking at the range in numbers of specific service categories, the number of educational services ranged from 11 to 87, the number of general child and family services ranged from 6 to 56 services, the number of general health services ranged from 2 to 61, and the number of services for population groups with a high risk of disadvantage ranged from 0 to 36. The number of supportive networks in each site ranged from 0 to 22.

Service coordination survey

The Service Coordination Study was built on the data collected in the baseline service mapping. It provided information about how services in CfC sites worked together. The logic model of the SFCS indicates that outcomes for children and families depend not just on service output, but also on how services and other initiatives are coordinated and work together at a strategic and operational level.

Most services used a combination of information sources to plan, allocate resources and identify service gaps in their communities. Just over three-quarters of services used feedback from service users, while many also used client information from services and community-level information. Just over half of all agencies involved with CfC used the SFCS Outcomes Framework data, compared with 5% of those without any involvement in CfC.

Respondents who held senior positions were significantly less involved in interagency arrangements than service delivery staff who responded to the survey. Respondents in frontline and service coordinator positions were most often the ones carrying out interagency activities. Agencies most commonly collaborated by referring clients to one another, exchanging information and conducting interagency meetings.

Respondents most frequently believed that the lack of integration between different levels of government, staff problems and competition for funding between agencies were the factors most likely to hinder effective partnerships. The factors most likely to be reported as promoting effective partnerships were 'respect and understanding of the needs of families' and a 'willingness to work together'. Many respondents also called for more commitment to interagency cooperation from senior staff, with many believing that strong leadership from agency administrators and a common goal of cooperation could facilitate effective partnerships.

Most respondents believed that there was a good understanding of the importance of the early years and were moderately confident that there was a shared vision about the needs of young children in their agencies.

The majority of respondents did at least some work with other service providers (70%), with about one-third saying that their service worked closely with other services most of the time. However, relatively few respondents (12%) thought that services currently worked together as a well-coordinated team and 58% thought that services were only partially coordinated at present.

A similar picture emerged when respondents were asked how often they believed services were provided in partnership with other agencies. About half of all respondents believed that services were provided though interagency partnership 'quite often' or 'sometimes' and very few said that services were 'rarely' or 'never' provided in partnership (11%).

Respondents were generally positive about providing services in partnership with other agencies, with 63% of respondents finding it 'very helpful' or 'mostly helpful'. Respondents working in agencies that currently provided services in partnership with other agencies most or all of the time were even more positive, and 96% of these respondents found interagency partnerships to be 'very helpful' or 'mostly helpful'.

To compare the level of service coordination between Stronger Families in Australia (SFIA) study sites, two composite indicators, Day-to-day Co-ordination and Effective Partnerships, were created. These indicators suggested that the majority of the sites had Moderate levels of Day-to-day Coordination and High levels of Effective Partnerships at baseline. A comparison of the SFIA and non-SFIA sites showed a similar spread between the indicators overall and suggests that the indicators are quite robust.

It seems that while many services are currently cooperating with one another to provide services to young children and their families, more could be done to collaborate further. A stronger commitment from senior managers and an explicitly stated goal of coordination could bring about more meaningful cooperation between agencies and improve service provision.

Fieldwork relating to partnership model and service coordination

As part of the Service Coordination Study and the Partnership Model Study, in-depth interviews with CfC key personnel were held during October and November 2006 in the 10 CfC sites where the SFIA study was being conducted. In each site between seven and 12 semi-structured interviews were conducted with key personnel involved with CfC. Respondents included senior managers and Project Managers of the Facilitating Partner (FP) organisations, CfC committee members, service providers, community members, local government representatives and FaCSIA State and Territory Officers.

Under the Facilitating Partner (FP) model, a Non-Government Organisation (NGO) was chosen as the lead agency in each CfC site. Often the NGO was locally based and well integrated into the site's existing service network. Overall the community-based nature of CfC was regarded by participants as positive. Most interviewees found that it gave the project credibility and instilled a sense of community ownership.

However, the effectiveness of the NGO in implementing CfC varied depending on the skills of the FP personnel and the resources at their disposal. In sites where FP personnel were able to develop relationships with stakeholders easily and to spread enthusiasm about CfC the implementation process progressed more smoothly. Support from the NGO's state or national offices was also important in the implementation process due to the complex administrative, management and legal tasks required from them as the leaders of a multi-million-dollar project.

Facilitating Partners (FPs) also received support from the government funding body, FaCSIA. The department's regional representatives, the State or Territory Officers, provided interpretation of FaCSIA requirements and guidance for the implementation.

In addition, many interviewees said that they thought there was a lack of clarity in the FaCSIA requirements and also said that delays in responses from the Department created difficulties. However it should be recognised that CfC represented an entirely new format for Government funding of NGOs, and in addition was a relatively large initiative. From a governmental perspective, therefore, comprehensive accountability arrangements are necessary whenever substantial funding is committed to a new model. FaCSIA responded to feedback from FPs. This included streamlining reporting requirements and decreasing the frequency of reports.

The implementation of CfC appears to have been useful as a vehicle for increasing the level of service cooperation in the sites. Under the model, the FPs were required to establish the Communities for Children Committee (CCC), a working group of child and family services and other stakeholders in their site. Most interviewees regarded the CCC very positively. They reported that the FPs had made a genuine effort at being open and inclusive by inviting all relevant stakeholder organisations as well as community members into the CCC. Many CCC members said how useful and rewarding their involvement was, especially in sites where no other early years network existed. Service providers could interact with others in the field and share knowledge. Most interviewees felt that the CCC had reduced segregation and competition among services and created mutual respect.

However, most sites had difficulties in recruiting all relevant stakeholders to the CCC especially parents of young children or other community members and representatives from some disadvantaged populations, such as Aboriginal people or people with a disability. Also many found it difficult to engage local businesses and most child care providers. Some FPs developed other avenues to engage these stakeholders.

Due to its community-based nature, CfC appears to have facilitated some improvements in service delivery and quality in the sites. Local plans were developed that gave stakeholders the opportunity to build on community strengths and address some service gaps and put early years strategies in place that they felt were most helpful for their site.

The selection of sites was a government decision based on a range of information. Some FPs believed the implementation of CfC was inhibited in some areas by the constructed boundaries of the CfC sites. Sites usually encompassed several suburbs or settlements, or even large rural or remote areas. These sites were sometimes contrary to locally defined geographic communities. In these areas this created significant obstacles to the FPs' ability to engage all relevant stakeholders, improve service coordination long-term and deliver services to young children and their families in all parts of the site.

At this stage it is not clear whether the implementation of CfC, using the FP model, has had a strategic impact in the sites; that is, whether it has been able to build sustainable service networks and improved services. It appears that continued financial engagement by state and federal governments remains essential.

1. Introduction

- 1.1 The Stronger Families and Communities Strategy: CfC

- 1.2 Description of the National Evaluation Framework

- 1.3 This report

A National Evaluation Consortium, comprising the Social Policy Research Centre (SPRC), UNSW, Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) and research advisers, was contracted by the Australian Government Department of Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaCSIA) to develop the evaluation framework for the Stronger Families and Communities Strategy (SFCS) 2004-2008.

The SFCS aims to: help families and communities build better futures for children; build family and community capacity; support relationships between families and the communities they live in; and improve communities' ability to help themselves. It contains four strands: Communities for Children (CfC), Invest to Grow (ItG), Local Answers (LA) and Choice and Flexibility in Child Care.

The national evaluation (NE) was designed to evaluate both the SFCS as a whole and each of three strands (CfC, ItG and LA) with the main focus on CfC. The NE is both formative - contributing to the development and refinement of policy and practice in relation to the Strategy - and summative - addressing the effectiveness of the Strategy and its implementation. This report contains a summary of the baseline data for the process evaluation for CfC. It provides an indication on the demographic and service delivery contexts in which CfC has been implemented in its 45 sites, and also reports on some of the issues relating to the early implementation of the CfC initiative. The various strands of data collection will be repeated in 2008, giving an indication of how these issues have changed as a result of the implementation of CfC.

1.1 The Stronger Families and Communities Strategy: CfC

Under the CfC initiative, non-government organisations are funded as 'Facilitating Partners' in 45 community sites around Australia to develop and implement a strategic and sustainable whole of community approach to early childhood development, in consultation with local stakeholders.

In implementing their local initiative, Facilitating Partners establish a CCC with broad representation from stakeholders in the community. The Facilitating Partner oversees the development of a four year Community Strategic Plan and annual Service Delivery Plans with the Committee and manages the overall funding allocation for the community. Most of the funding has been allocated to other local service providers to deliver the activities identified in the Community Strategic and Service Delivery Plans.

Examples of activities that have been implemented in the sites are:

- home visiting programs

- early learning and literacy programs

- early development of social and communication skills

- parenting and family support programs

- child nutrition programs

- community events to celebrate the importance of children, families and the early years. 1

According to the logic model of the Initiative, service effectiveness is dependent not only on the nature and number of services, but also on how seamless the service delivery is. Thus much of the CfC effort has been devoted not only to providing new services, but to 'joining up' existing services by increasing service coordination and cooperation.

1.2 Description of the National Evaluation Framework

The national evaluation framework is designed to evaluate the SFCS in relation to the Outcomes Framework developed by FaCSIA2. The Outcomes Framework aligns with the four priority areas of the National Agenda for Early Childhood: healthy young families; supporting families and parents; early learning and care; and child-friendly communities. A fifth priority area specifically relates to the CfC initiative; family and children's services work effectively as a system.

The key questions for the NE are:

- Have outcomes for children and families in relation to the four key action areas improved as a result of the Strategy?

- Which lessons have been learnt on how to achieve and sustain better outcomes for children 0-5 and their families /communities?

- Is early investment effective in terms of cost and outcomes for children?

- For which children, families or communities is it effective?

- What aspects of the model are effective?

- How effectively have resources been used?

- Has the SFCS achieved its objectives?

To answer these questions, the national evaluation framework consists of the interlocking components presented in Table 13.

| Process evaluation | Outcome evaluation | Process & outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Communities for Children | Comprehensive Community Profile: - demographic profile - service mapping Service coordination study Partnership model study |

Longitudinal survey of families in 10 CFC sites (3 waves) Monitoring of secondary data |

Cost effectiveness study |

| Invest to Grow | Analysis of local evaluation reports | ||

| Cross-strategy | Themed studies Promising practice profiles Progress reports analysis |

The bulk of the National Evaluation is focused on evaluating CfC. The overall evaluation questions for CfC are:

- Have outcomes for children and families in CfC sites improved as a result of the Initiative?

- Do services in CfC sites work more effectively as a system?

- Are CfC communities more child-friendly?

- How successful has the Facilitating Partner model been in bringing about these changes?

The evaluation of CfC comprises an outcomes, process and a cost effectiveness evaluation. This report is concerned with the process evaluation. The logic model of CfC asserts that the Facilitating Partner model will improve services in CfC communities and strengthen communities, ultimately improving outcomes for children and families. The aim of the CfC process evaluation is to determine whether and how services in the communities have improved. The process evaluation includes a comprehensive community profile of each of the CfC communities, an assessment of how well services for young children in the community work together, and a study of the effectiveness of the SFCS partnership model.

1.3 This report

This report contains information on baseline data for the process evaluation in CFC sites (the shaded cell in Table 1). That is:

- Demographic profiles

- Service mapping

- Service coordination survey

- Field work relating to partnership model and service coordination.

1. Further details of the SFCS and CfC are available from www.facs.gov.au/internet/facsinternet.nsf/aboutfacs/programs/sfsc-sfcs.htm

2. The SFCS national evaluation outcomes framework is available from www.facs.gov.au/internet/facsinternet.nsf/vIA/sfcs_evaluation/$File/sfcs_%20evaluation_program.pdf

3. The national evaluation framework is available from www.facs.gov.au/internet/facsinternet.nsf/vIA/sfcs_evaluation/$File/sfcs_evaluation.pdf

2. Demographic profiles

A demographic profile of each community was compiled using data from the Census of Population and Housing, 2001. The key purpose was to provide contextual information about the social and economic characteristics of CfC sites, and the demographic characteristics of children aged under five and their families. This provides a backdrop that helps to understand the different contexts in which CfC have been implemented. The National Evaluation will use this data for understanding the implementation and impact of CfC in each area.

2.1 Method

The profiles draw on customised and publicly available data from the Census of Population and Housing, other Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) data and other relevant data. Data was obtained for populations living within the CfC boundaries, as negotiated between the individual CfC sites and FaCSIA. As a result, each CfC site has been defined differently, and site boundaries do not necessarily share the geographic boundaries used in statistical data collections. For example, some sites were defined as one or more suburbs or postcodes and others were defined as one or more Statistical Local Areas or Collection Districts (as defined by the ABS). While data has been tailored for the precise area as far as possible, it should be recognised that statistical areas do not perfectly match service delivery areas. Further, the areas may not perfectly capture children and families who are potential service users. Living within the defined boundaries is not an explicit requirement for service use, so CfC programs can serve some children and families who live outside their boundaries.

The data in the demographic profiles includes information about 0-5 year olds in the CfC site before the CfC initiative began (primarily using 2001 Census data). The data includes information about the families of 0-5 year olds in each site, including family structure, parental unemployment, and mothers' language and English proficiency. Some socio-economic data in the profiles relates to the broader population (not just children 0-5 and their families) including participation in education, educational attainment, birthplace, unemployment rates, motor vehicle ownership, and the SEIFA Index for disadvantage.

The demographic profiles include information about the:

- number 0-5 year olds as a percent of the total population (excluding overseas visitors)

- proportion of children 0-5 who are ATSI

- proportion of children 0-5 attending preschool

- proportion of children 0-5 living in lone parent households

- proportion of children 0-5 living in families with gross incomes of less than $500 per week

- proportion of children 0-5 with mothers who speak English 'not well' or 'not at all'

- proportion of children with one or two parents unemployed

- proportion of households with no motor vehicle

- proportion of persons aged 15 years and over who attained Year 12 or equivalent as highest level of schooling

- proportion of the population born outside main English speaking countries

- proportion of children living in relatively disadvantaged areas (according to SEIFA)

- Rise/decline in proportion of the population who are 0-5 1991-2001

To help Facilitating Partners and Local Evaluators to understand population trends in their community and to plan and target early intervention and prevention initiatives within their communities, reports on each site were distributed to Facilitating Partners. A report for Australia, which provides comparative information, was posted on the Communities and Families Clearinghouse Australia (CAFCA) website (http://www.aifs.gov.au).

2.2 Results

Demographic data in CfC sites and Australia are summarised in Table 2 and discussed below.

| CfC sites (%) | Australia (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Proportion of population aged 0-5 | 9 | 8 |

| 0-5 year olds who are ATSI | 9 | 4 |

| 0-5 year olds in lone parent households | 21 | 15 |

| 0-5 year olds in families with weekly incomes <$500 | 26 | 18 |

| 0-5 year olds with mothers who speak English 'not well' or 'not at all' | 5 | 3 |

| 0-5 year olds with one or two parents unemployed | 10 | 7 |

| Households with no motor vehicle | 11 | 10 |

| Persons aged 15 years and over who attained Year 12 or equivalent as highest level of schooling | 28 | 38 |

| Persons born outside main English speaking countries | 20 | 20 |

Children in CfC sites

In August 2001, there were 113 695 children aged 0-5 years living in 81 071 families in the areas now covered by CfC.

In the CfC areas, children comprised on average 9% of the population, compared with 8.0% of the population throughout Australia. The sites with the highest proportions of children aged 0-5 were those with large Indigenous populations. In Katherine, 19.9% of the population were aged 0-5, as were 13.6% of the population in East Arnhem and 12.9% of the population in the Palmerston/Tiwi site.

Indigenous children

There were 9780 Indigenous children aged 0 to 5 years in the CfC sites. Indigenous children represented 9% of children aged 0-5 in the sites, compared with 4.0% across Australia. East Arnhem had the highest proportion of children who were Indigenous (73%), followed by Katherine (58%) and East Kimberley (48%). Less than 1% of the 0-5 year old population was Indigenous in Fairfield, Hume/Broadmeadows, Brimbank and Greater Dandenong.

Family type

Three quarters (75%) of children aged 0 to 5 years (84 976 children) counted at home in CfC sites (not visitors) were living in couple families, compared with 82% in Australia as a whole. 23403 children aged 0 to 5 (21%) counted at home in CfC sites were living in sole parent families, compared with 15% across Australia. 5316 children aged 0-5 (or 5%) were living in multifamily arrangements, compared with 3% of children in this age group across Australia.

However, the pattern was different for Indigenous children. A smaller proportion of Indigenous children aged 0-5 were living in sole parent families in CfC sites compared with Australia (27% compared with 29% across Australia) and a larger proportion were living in multi-family households (19% compared to 13%).

The sites with the highest proportions of children 0-5 living in sole parent families included Launceston (35% of children); Kingston-Loganlea (34% of children), and Inala-Ipswich (30% of children). The sites with the lowest proportion of children living in sole parent families were in sites with high proportions of Indigenous children- East Arnhem (3%), West Pilbara (8%) and Katherine (10 %).

Parental unemployment

In 2001, there were 11,470 children aged 0-5 years counted at home in the CfC areas living in families with at least one parent who was unemployed (10%). In contrast, 7% of children aged 0-5 across Australia lived in families with at least one parent unemployed. The sites with the highest proportions of children aged 0-5 years living in families with an unemployed parent (between 14 and 15%) were Kingston/Loganlea, Fairfield, Hume/Broadmeadows, Inala-Ipswich and Mirrabooka. Sites with the lowest proportions of children living in families with an unemployed parent were East Arnhem, West Pilbara and East Kimberley (less than 4% of children 0-5)4.

Family income

In 2001, over a quarter of children aged 0 to 5 years (26%) in CfC sites lived in families with incomes under $500. CfC sites had higher proportions of children in low income families than across Australia, where 18% lived in families with incomes under $500. The sites with the highest proportion of children 0-5 living in families with weekly incomes under $500 were in Hume/Broadmeadows, Inala-Ipswich, Mirrabooka, Launceston, and East Arnhem. The lowest were in West Pilbara (8% of children 0-5 in families earning less than $500 per week) and Mount Isa (13%).

Parental language and English proficiency

In CfC sites, there were 88188 (78%) children 0-5 who had mothers who spoke English only. Only 4540 children (4%) had mothers who spoke other languages and spoke English 'not well' or 'not at all'. The proportion of children aged 0 to 5 years with mothers who spoke English 'not well' or 'not at all' was slightly higher in CfC sites (5%) than across Australia (3%).

Compared with the national average (78%), a higher proportion of children aged 0-5 years in CfC sites had mothers who spoke languages other than English (78% compared to 74%). The largest group of children in CfC sites with mothers who spoke languages other than English were those who spoke Vietnamese (3%); Arabic (2%) and Turkish (1%).

The sites with the lowest proportions of children aged 0-5 with mothers who spoke only English were in Fairfield (21%), Hume/Broadmeadows (29%) and East Arnhem (33%). More than 95% of children in Gladstone, East Gippsland, Bendigo, South East Tasmania and Dubbo/Narromine had mothers who spoke English only.

Cultural diversity in CfC sites

In CfC sites, about the same proportion of the population were born in Australia as for the country as a whole (72% of the population in CfC sites were born in Australia compared with 72% nationally). In CfC sites and in Australia as a whole, the largest groups born outside Australia were born in the United Kingdom and New Zealand.

Twenty percent of people in CfC sites and in Australia as a whole were born outside the main English speaking countries (Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, South Africa the United Kingdom and United States). The largest group born outside the main English speaking countries were those born in Italy and Vietnam, in both CfC sites and the country as a whole.

The sites with the highest proportions of the population born outside the main English speaking countries were Fairfield (59%) and Brimbank (50%). Dubbo/Narromine, Bendigo and South East Tasmania each had less than 8% of the population born outside the main English speaking countries.

Educational attainment, persons aged 15 and over

A lower proportion of persons aged 15 and over in CfC sites had completed Year 12 or an equivalent level of schooling than across Australia (28% compared with 38%). The sites with the lowest proportions of the population aged 15 and over who had completed Year 12 or equivalent were South East Tasmania (17%), Burnie (18%), Launceston (20%), Port Augusta (20%) and East Arnhem (21%). The sites with the highest proportion of the population who had completed Year 12 were Inner North Canberra (62%) and Fairfield (35%).

Motor vehicle ownership

A similar proportion of households in CfC sites (11%) had no motor vehicle, compared with the national figure (10%). High proportions of households had no vehicle in East Arnhem (28%) and Katherine (19%). Less than 6% of households had no motor vehicle in Cranbourne, Coomera- Northern Gold Coast and West Pilbara.

Socio-Economic Indices for Areas (SEIFA) Index of Disadvantage

Based on 2001 Census data, the SEIFA Index of Disadvantage includes variables that either reflect or measure disadvantage, such as education, income and occupation, housing, access to the Internet, and Indigeneity. The Indices show relative disadvantage (but do not quantify it).

Indices of Disadvantage were ranked for the Statistical Local Areas that cover the Communities for Children site. Sites could be covered by more than one SLA, or by part (or parts) of an SLA. As shown in Table 3, 23 of the 45 sites are covered by an SLA with a score that placed them in the most disadvantaged 10% of areas in Australia. The sites that contained the lowest ranked SLAs were East Arnhem, East Kimberley, Palmerston / Tiwi, Katherine, Inala-Ipswich and North-West Adelaide (scores all under 800). Fourteen sites had SEIFA scores in the highest 50% of areas in Australia. The sites with SLAs with the highest scores (lowest relative disadvantage) were Inner North Canberra, East Arnhem, North-West Adelaide, Salisbury, Palmerston / Tiwi, East Gippsland, Dubbo / Narromine and Lower Great Southern.

| Had one or more SLA in the lowest 10 percent in Australia | SLA in lowest 10 to 25 percent of areas | SLA in lowest 25 to 50 percent of areas | SLAs in lowest 50 to 75 percent of areas | SLAs in lowest 75 to 90 percent of areas | SLAs in highest 10 of areas in Aust |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bendigo | Bendigo | Armadale | Bendigo | Inner North Canberra | Inner North Canberra |

| Blacktown | Blacktown | Bendigo | Dubbo / Narromine | ||

| Brimbank | Campbelltown | Burnie | East Arnhem | ||

| Burnie | Cranbourne | Cairns | East Gippsland | ||

| Cairns | Dubbo / Narromine | Dubbo / Narromine | Frankston | ||

| Deception Bay | Gladstone | East Gippsland | Inner North Canberra | ||

| East Arnhem | Inala-Ipswich | Frankston | Lower Great Southern | ||

| East Kimberley | Launceston | Gladstone | Nthn Gold Coast (Coomera) | ||

| Fairfield | Lismore | Inner North Canberra | NW Adelaide | ||

| Greater Dandenong | Lower Great Southern | Katherine | Palmerston / Tiwi | ||

| Hume/Broadmeadows | Miller | Launceston | Salisbury | ||

| Inala-Ipswich | Mirrabooka | Lower Great Southern | Swan Hill | ||

| Katherine | Murray Bridge (RC) | Mirrabooka | West Pilbara | ||

| Kingston Loganlea | Murwillumbah | Mt Isa | Wyong | ||

| Kwinana | NW Adelaide | Murray Bridge | |||

| Launceston | Onkaparinga | Murwillumbah | |||

| Murray Bridge | Port Augusta | Nthn Gold Coast (Coomera) |

|||

| NW Adelaide | Raymond Terrace | NW Adelaide | |||

| Onkaparinga | SE Tas | Raymond Terrace | |||

| Palmerston / Tiwi | Shellharbour | Salisbury | |||

| Salisbury | Taree | West Pilbara | |||

| SE Tas | West Townsville | ||||

| West Townsville | Wyong | ||||

| 23 sites | 23 sites | 21 sites | 14 sites | 1 site | 1 site |

Summary

In summary, populations in CfC sites appear more disadvantaged on most of the relevant indicators. More than half of the sites (23) were covered by an SLA (or part thereof) which had a SEIFA score that placed it amongst the most disadvantaged 10 percent of areas in Australia. CfC sites had higher proportions of children aged 0-5 who live in lone parent households than the national average, higher proportions with a parent unemployed, and higher proportions who live in low-income families. Families with children aged 0-5 years in CfC areas were also more culturally diverse. Although the same proportion of the overall population was born outside the main English speaking countries in Australia and in CfC sites, there were higher proportions of children in CfC sites with mothers who don't speak English very well. CfC sites also had higher proportions of children who were Indigenous, compared with Australia as a whole. Populations in CfC areas were also less likely to have attained Year 12 or equivalent levels of qualifications.

4. That there are lower proportions of children living in families with unemployed parents in sites with high Indigenous populations may be because there are high rates of participation in CDEP in Indigenous areas.

3. Service mapping

This section of the report provides an overview of the baseline service mapping component of the process evaluation. The aim was to establish a baseline measure of the range of services and initiatives in place prior to, or early in the implementation of the local community strategic plan in each CfC site. The analysis was based on data collected from a variety of sources including service directories, planning documents, previous mapping exercises and a short questionnaire sent to organisations in the local area. The service mapping will be repeated towards the end of 2007 to build a picture of types of interventions provided by CfC and determine changes in the range and type of services available in the site.

3.1 Method

In December 2005, the baseline service mapping questionnaire was distributed via email to the 45 Project Managers in each Facilitating Partner organisation. The questionnaire asked for baseline data concerning services specifically for children 0-5 years and their families operating within the CfC site. Project managers were also asked to identify any service gaps as a result of their service mapping and to list any Local, State or Commonwealth Government initiatives currently operating in the area.

Analysis of the data supplied by the 45 sites revealed significant inconsistencies in the manner in which the questionnaires had been completed. For example, some respondents included venues that did not deliver specific services to young children and their families, such as retail outlets, RSL clubs and swimming pools. In other cases whole sections of the service network appeared to be missing. Some sites, for example, listed no general practitioners (GPs) and others no education services.

To get a more accurate reflection of the service network, a second round of data collection was conducted. The services listed for each site were sorted and coded into new categories. All data were categorised in the same way to ensure comparability across the 45 sites. Inappropriate services were removed and the gaps in the data provided were highlighted. From this re-categorisation process, a very specific service typology was developed. This typology took into account the kinds of services being reported in the sites and accommodated the different nature of services and the different roles of organisations in each area. For example, many of the service maps included organised networks that did not deliver services on the ground but played a crucial role in the sector and thus needed to be reflected in the mapping.

The new typology (see Table 4) allowed for meaningful comparison between the sites and identification of any gaps in the data that could be checked with Project Managers. Service maps were re-sent with the new typology for Project Managers to check how accurately the initial data reflected the service network in their site. Project Managers were asked to add any services that had been omitted from the original mapping exercise.

The returned data varied considerably between sites. It is not known how much of the variation is a result of differences in the nature and number of services in each site and how much was due to reporting bias or error.

Although the number of services varied between sites, the number of services was more consistent in the revised service mapping than in the original service maps. When FPs supplied the original Baseline Service Mapping data, the mean number of reported services in each site was 80. After this data was categorised and FPs revised their original spreadsheets, the average reported number of services in each site rose to 97 (a 10% increase). There was a dramatic increase in the number of services reported by some sites. In one site, for example, the number of reported services rose from 38 to 227 when they revised their data (a 493% increase). The increase was less marked in many other sites, but almost all reported a larger number of services in the revised service mapping. Some reported fewer services as initial data had included venues or services not specific to young children and their families.

| Service Category | Service type |

|---|---|

| 1. Education | 1.1 Early education services e.g. -

1.2 Primary schools 1.3 Other e.g. -

|

| 2. Population groups with higher risk of disadvantage |

2.1 Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD)

|

| 3. General child & family | 3.1 Community hubs e.g.

3.6 Early intervention 3.7 Family support e.g. -

3.9 Other e.g. -

|

| 4. Health | 4.1 Allied Health e.g. -

4.4 GPs and medical centres 4.5 Hospital 4.6 Maternal health e.g. -

4.8 Specialist services e.g. -

|

| 5. Supportive networks, e.g. organisations involved with the planning and development of services |

5.1 State Government Departments

5.2 Interagency chairs 5.3 GP Peak bodies 5.4 Childcare peak bodies 5.5 Early years partnerships e.g.

|

Venues where no specific service can be listed should be omitted e.g.

|

|

| Site | 1. Education | % | 2. Population groups with a higher risk of disadvantage |

% | 3. General child & family |

% | 4. Health | % | 5. Supportive networks |

% | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armadale | 66 | 29 | 29 | 13 | 56 | 25 | 54 | 24 | 22 | 10 | 227 |

| Blacktown | 47 | 30 | 13 | 8 | 25 | 16 | 59 | 38 | 12 | 8 | 156 |

| Brimbank | 42 | 44 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 96 |

| Cairns | 51 | 48 | 16 | 15 | 28 | 26 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 107 |

| Campbelltown | 19 | 28 | 5 | 7 | 22 | 32 | 15 | 22 | 7 | 10 | 68 |

| Dubbo | 67 | 37 | 28 | 16 | 42 | 23 | 37 | 21 | 6 | 3 | 180 |

| East Arnhem | 21 | 37 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 18 | 12 | 21 | 10 | 18 | 57 |

| East Gippsland | 87 | 55 | 11 | 7 | 13 | 8 | 39 | 25 | 7 | 5 | 157 |

| East Kimberley | 11 | 26 | 8 | 19 | 9 | 21 | 13 | 31 | 1 | 2 | 42 |

| Frankston North | 33 | 47 | 3 | 4 | 17 | 24 | 15 | 21 | 2 | 3 | 70 |

| Gladstone | 68 | 34 | 14 | 7 | 38 | 19 | 61 | 31 | 17 | 9 | 198 |

| Greater Dandenong | 34 | 40 | 13 | 15 | 22 | 26 | 14 | 16 | 3 | 4 | 86 |

| Hume/ Broadmeadows | 46 | 41 | 36 | 32 | 16 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 10 | 111 |

| Inala | 32 | 33 | 9 | 9 | 29 | 30 | 18 | 19 | 9 | 9 | 97 |

| Inner North ACT | 41 | 42 | 3 | 3 | 32 | 33 | 17 | 18 | 4 | 4 | 97 |

| Katherine | 47 | 52 | 15 | 17 | 13 | 14 | 9 | 10 | 7 | 8 | 91 |

| Kingston Loganlea | 28 | 39 | 9 | 13 | 25 | 35 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 71 |

| Kwinana | 28 | 41 | 3 | 4 | 29 | 42 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 69 |

| Launceston | 22 | 42 | 6 | 11 | 11 | 21 | 9 | 17 | 5 | 9 | 53 |

| Lismore | 41 | 39 | 20 | 19 | 25 | 24 | 14 | 13 | 6 | 6 | 106 |

| Mirrabooka | 35 | 48 | 10 | 14 | 15 | 21 | 8 | 11 | 5 | 7 | 73 |

| Mt Isa | 25 | 40 | 11 | 18 | 12 | 19 | 8 | 13 | 6 | 10 | 62 |

| Murwillumbah | 18 | 46 | 5 | 13 | 7 | 18 | 8 | 21 | 1 | 3 | 39 |

| North Gold Coast | 32 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 11 | 12 | 23 | 3 | 6 | 53 |

| Onkaparinga | 49 | 36 | 7 | 5 | 37 | 27 | 33 | 24 | 9 | 7 | 135 |

| Palmerston | 26 | 41 | 5 | 8 | 15 | 24 | 16 | 25 | 1 | 2 | 63 |

| Port Adelaide | 46 | 47 | 9 | 9 | 18 | 18 | 16 | 16 | 9 | 9 | 98 |

| Port Augusta | 21 | 26 | 24 | 29 | 23 | 28 | 12 | 15 | 2 | 2 | 82 |

| Raymond Terrace | 15 | 22 | 7 | 10 | 13 | 19 | 21 | 31 | 12 | 18 | 68 |

| Salisbury | 25 | 46 | 3 | 6 | 13 | 24 | 11 | 20 | 3 | 6 | 55 |

| SE Tasmania | 35 | 38 | 2 | 2 | 23 | 25 | 23 | 25 | 10 | 11 | 93 |

| Shellharbour | 53 | 38 | 6 | 4 | 31 | 23 | 40 | 29 | 8 | 6 | 138 |

| Southern Lakes | 41 | 38 | 10 | 9 | 17 | 16 | 35 | 32 | 5 | 5 | 108 |

| Swan Hill Robinvale | 49 | 38 | 25 | 19 | 25 | 19 | 29 | 23 | 1 | 1 | 129 |

| Townsville | 15 | 22 | 14 | 21 | 25 | 37 | 12 | 18 | 2 | 3 | 68 |

| Total | 1316 | 39 | 408 | 12 | 769 | 23 | 693 | 20 | 217 | 6 | 3403 |

Data from other sites will be added to subsequent reports.

Note: May not add up to 100% due to rounding.

3.2 Results

FPs were asked to return their revised baseline service mapping data by the end of March 2007. At 1 May 2007, 35 of the 45 sites had returned their data and so this preliminary presentation of baseline service mapping data does not take into account services that were available in the remaining 10 sites.

The total number of reported services varied from 53 in Launceston to 227 in Armadale. Most sites reported that the highest proportion of services fell into the broad categories of 'Education' or 'General Child and Family', which included community hubs, information services, counselling and family support services (Table 5). Overall, 39% of services in each site fell within the category of 'Education' and 23% were classified as 'General Child and Family'.

The rates varied between sites. More than 55% of services for young children and their families in East Gippsland and just under half of these services in the Cairns, Frankston North and Murwillumbah sites were reported to be educational (48%, 47% and 46% respectively). In contrast, only 22% of services in Townsville and 29% of those in Armadale were reported to be educational.

The number of 'Health' services reported in each site varied markedly. The Brimbank and Hume/ Broadmeadows sites listed only two 'Health' services each, and Kingston Loganlea and Kwinana only six, compared to Blacktown and Armadale, which listed 59 and 54 services respectively.

FPs were asked to assign services to more detailed categories. A comprehensive list of these categories can be found in the Service Mapping Typology (Table 4).

No GPs, dentists or applied health practitioners were reported in Brimbank and Hume/ Broadmeadows, and neither FP reported any hospitals serving their site. Conversely, several other sites provided extensive listings of medical services in their areas. The wide range of responses could be a result of respondent error or could reflect the actual range of medical services available in each site.

As with the 'Health' category, the Armadale site reported one of the largest numbers of services in the 'Supportive Services' category, which incorporates organisations involved with the planning and development of services. There were 22 'Supportive Services' reported in Armadale and 17 reported in Gladstone, compared to 1 or 2 in several sites including Swan Hill/Robinvale and Palmerston and none in Brimbank.

Neither Swan Hill/Robinvale nor Palmerston reported any services for several sub-categories beneath 'Supportive Services' including 'State Government departments', 'Local Councils' and 'Associations and Committees'. Again, it is likely that some of these services were available in these areas.

3.3 Summary and discussion

In summary, the data provided as at 1 May 2007 suggest that education services are the most prevalent services for children aged 0-5 years and their families in the CFC sites (39%), followed by general child and family services (23%) and health services (20%). An additional 12% of services targeted population groups with a higher risk of disadvantage. Nearly all FPs reported the existence of supportive networks in their site.

There was substantial variety in the number and type of services and networks available in each site. Overall, the number of services in the sites ranged from 39 to 227. Looking at the range in numbers of specific service categories, the number of educational services ranged from 11 to 87, the number of general child and family services ranged from 6 to 56 services, the number of general health services ranged from 2 to 61, and the number of services for population groups with a higher risk of disadvantage ranged from 0 to 36. The number of supportive networks in each site ranged from 0 to 22.

Despite substantial effort to ensure the service mapping data was accurate, comprehensive and consistent between the sites, it is likely that some errors and inconsistencies remain. Despite the problems in data accuracy, the results are likely to represent a reasonable picture of the number and variety of services for children aged 0-5 years and their families in the CFC sites at the commencement of the initiative.

The service mapping exercise highlighted the considerable difficulties inherent in an exercise such as this. Definitional issues are very problematic as there are no clear and universally accepted definitions of a 'service'. More importantly, it is very difficult for FPs to know the sum total of services in their area. In order to do so they need to rely on a variety of sources, as there is no central database or register of services. In addition services are in a continuous state of change. New services emerge, services change their remit, move premises or cease to operate. So even though FPs were required to undertake a service mapping exercise as part of the development of their strategic plans, they found this mapping exercise - which was considerably more rigorous than that required for their plans - enormously challenging.

4. Service coordination study

The Service Coordination Study was built on the data collected in the baseline service mapping. It provides information about how services in CfC sites work together. The logic model of the SFCS indicates that outcomes for children and families depend not just on service output, but also on how services and other initiatives are coordinated and work together at a strategic and operational level.

4.1 Method

The service coordination study involved:

- A postal and email survey of contacts in relevant agencies in each CfC community, administered by the SPRC ('the snapshot questionnaire').

- Additional semi-structured interviews with approximately ten key personnel from those CfC communities in which the Stronger Families in Australia study was conducted. Most of these interviews were held face-to-face by the SPRC. Key personnel who were unavailable during the fieldwork period participated in a telephone interview. The findings from this intensive fieldwork stage of the service coordination study are reported below (see Section 5).

The lists of services collected in the baseline service mapping formed the sample for the survey.

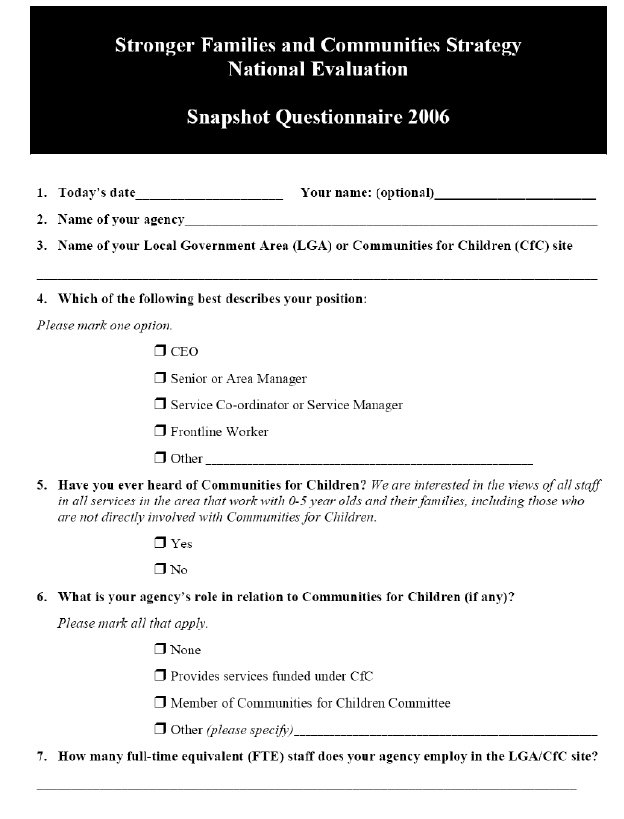

4.2 The Snapshot survey

The snapshot survey was designed to assess how services in CfC areas are working together to achieve outcomes for children aged 0-5 and their families. The term 'snapshot' was used to denote that the survey was taking a picture of the extent of coordination at a particular time, with the intent of taking another picture after CfC had been in operation for some time. The survey was conducted in 2006.

Instruments

Initially two questionnaires were developed, one for assessing service coordination at the strategic level and one, at the operational level. The strategic level questionnaire was developed to establish the level of interagency working and cooperation in relation to planning, coordinating and commissioning services. The operational level questionnaire addressed how well services work together on the ground - do they know about each other? Do they find it easy to refer to each other? Are there information-sharing protocols, which allow services to know who else is involved with families? Are there ways of coming together to discuss cases that cause concern?

Questions were developed following a literature search of indicators for collaboration among agencies, and of questions and questionnaires used in similar studies, both in Australia and overseas. Several authors discussed indicators of successful collaboration and different types of collaboration among agencies. For example, Sullivan, Gilmore and Foley (2002) distinguished between three basic methods of collaboration: activity (e.g. multi-agency working groups); structural (e.g. co-location of offices); and financial (e.g. cost-sharing for services). Walker (2000) suggested that different forms of collaboration can be placed along a continuum from less to more collaboration, with a referral network as the least complex form and a collaborative alliance the most complex. Similarly, Himmelman (2001) grouped collaboration activities into four basic categories along a developmental continuum: networking, coordinating, cooperating and collaborating. A selection of indicators covering all methods and categories of collaboration were included in the questionnaires.

Questions relating to the current level, barriers and facilitators to collaboration were based on questions from the National Center for Family Support (2000) and the VicHealth Partnerships Analysis Tool (The Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, hereafter VicHealth 2003). Other questions were based on those used by the SPRC in the evaluation of the Demonstration Projects in Integrated Community Care for the NSW Ageing and Disability Department.

Both questionnaires were piloted with strategic and operational level personnel in three CfC sites: Miller, East Gippsland and Mirrabooka. The Strategic level questionnaire was piloted with a total of nine people, and the Operational level one, with eight. Both questionnaires were then refined according to the interviewees' feedback. In addition, feedback from other researchers, including evaluators employed by CfC at a local level (Local Evaluators (LE)), was incorporated.

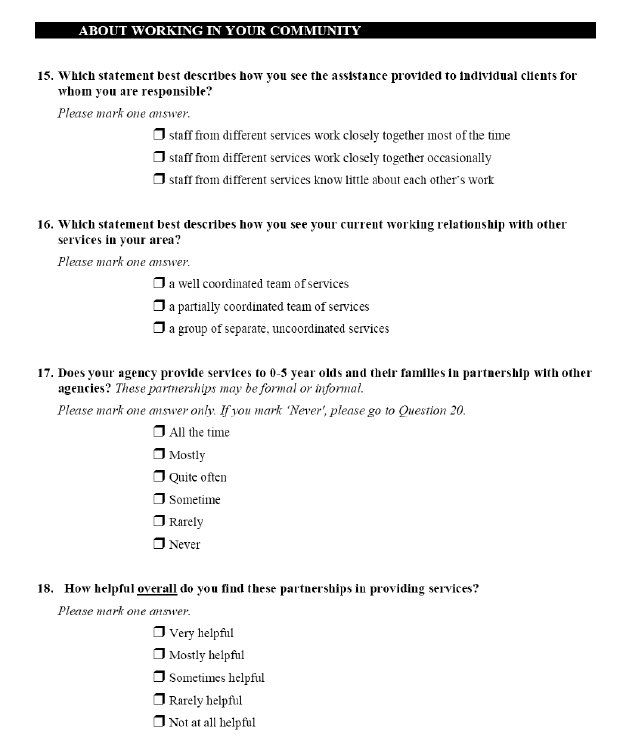

After the initial distribution of the questionnaires, it became clear that many services found it confusing to deal with two separate questionnaires (see below). Therefore the Strategic and Operational level snapshot questionnaires were condensed into a single 'Snapshot questionnaire' (Appendix A). This questionnaire explored different aspects of service coordination as outlined in Table 6 below.

| Domain | Indicators |

|---|---|

| Better service coordination | Involvement in joint activities (Q.10) Ratings of joint activities (Q.10) Level of staff involved in coordination (Q.11) History, extent and ratings of service coordination (Q.15-21) |

| Facilitators of coordination | Facilitating factors (Q.13) |

| Barriers to coordination | Hindrances (Q.12) |

| Use of key principles of SFCS | Use of information to guide planning (Q.9) Incorporation of key principles (Q.14) |

Sample

The sample for this study was based on the service networks in the sites, as defined in the service mapping exercise described above. The entire network of agencies providing services to children aged 0-5 and their families in CfC sites was included, not only those funded under CfC or involved in some other way so that changes in how services work together throughout the service network could be examined.

Initially, both questionnaires were sent to a single contact in each agency listed in the baseline service maps completed by FPs. That single contact was then requested to forward each questionnaire to two relevant staff members in their agency (an operational level manager and a strategic level manager). Follow up with FPs and LEs indicated that this step in the process was confusing for some services, especially for small services, which may have only one relevant staff member performing both ‘strategic’ and ‘operational’ roles. In response, the strategic and operational snapshot questionnaires were condensed into a single ‘Snapshot Questionnaire’. The refined distribution process and format of the questionnaire made it easier to understand and quicker to complete, reducing the burden on respondents. Note, however, that the completed strategic and operational versions were still used in the analysis.

To further improve the survey response rates, FPs and LEs were actively involved in the distribution process. Distribution of the survey was tailored according to the advice and preferences of the FPs and LEs in each site. The questionnaires were administered either by post or email (in some sites, both), and in some cases accompanied by an introductory letter from FPs and LEs. Many FPs and LEs also played a role by distributing the questionnaires in person throughout their communities and at interagency or other meetings.

The snapshot questionnaires were distributed to services in 41 of the 45 CfC sites. Consultations with the FPs and LEs of four sites containing remote Indigenous communities (Palmerston & Tiwi Islands, Katherine, East Kimberley and East Arnhem) indicated that the survey instrument was not culturally appropriate for the service providers of those areas. Consequently, the surveys were not distributed in Katherine, East Kimberley, East Arnhem and the Tiwi Islands. They were, however, distributed to services in Palmerston, an urban area with a mainly non-Indigenous population.

4.3 Results

Data was collected from staff of agencies that were identified through the CfC Baseline Service Mapping. The sample included staff from agencies that were not in any way involved with CfC, as well as staff from agencies involved with the initiative.

More than one-third of respondents (36%) did not record their position within their agency in any of the categories prescribed by the questionnaire (Table 7). Instead, some respondents wrote down their profession, for example teacher, GP, social worker or librarian. Of those respondents who did tick one of the prescribed positions, the highest proportion worked as Service Coordinators or Service Managers (32%) within their agencies, followed by Frontline Workers (15%), Senior or Area Managers (11%) and CEOs (5%).

| Per cent | |

|---|---|

| CEO | 5 |

| Senior or Area Manager | 11 |

| Service Coordinator or Service Manager | 32 |

| Frontline Worker | 15 |

| Other | 36 |

| Missing | 2 |

| Total | 100 |

(N = 482)

Note: May not add up to 100% due to rounding

Most agencies with which respondents were affiliated employed at least some full-time equivalent staff (Table 8), but they tended to be small enterprises. Only 12 per cent of respondents’ agencies had no full-time equivalent staff employed in the Local Government Area (LGA)/CfC site. Most agencies had a small number of full-time equivalent staff: 42% had less than five, and more than 55% had less than ten full-time staff.

| Per cent | |

|---|---|

| 0 | 12 |

| 0.1-0.5 | 3 |

| 0.6-0.9 | 2 |

| 1-1.9 | 8 |

| 2-2.9 | 7 |

| 3-3.9 | 5 |

| 4-4.9 | 5 |

| 5-5.9 | 3 |

| 6-9.9 | 11 |

| 10-49.9 | 13 |

| 50-400 | 6 |

| Missing | 25 |

| Total | 100 |

(N = 482)

Table 9 shows that only 27% of all agencies provided services solely to 0-5 year old children and their families. Just under half of all agencies devoted at least half of their activities to services for 0-5 year olds and their families.

(N = 482)

Note: May not add up to 100% due to rounding

Overall, survey respondents had a high level of recognition of CfC. The results in Table 10 show that 70 per cent of all respondents had heard of the initiative.

| Per cent | |

|---|---|

| Yes | 70 |

| No | 8 |

| Missing | 22 |

| Total | 100 |

(N = 482)

Level of Agency Involvement in CfC

Although many agencies in CfC sites had some role in relation to CfC, Table 11 shows that two thirds of survey respondents were from agencies that were not involved with the project in any way. A sizeable minority (36 percent) of respondents came from an agency that was a member of the CfC committee and only 28 percent came from an agency that provided services funded under CfC. Since the defined criteria are not exclusive, the agency roles can overlap.

|

Per cent |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Missing | Total | |

| Member of Communities for Children Committee | 36 | 50 | 14 | 100 |

| Provides services funded under CfC | 28 | 58 | 14 | 100 |

| None | 19 | 67 | 14 | 100 |

(N = 482)

The proportion of activities devoted to services for 0-5 year old children and their families was similar for agencies with and without involvement in CfC. Table 12 shows that 62 percent of agencies with some involvement with CfC devoted 50 percent or more of their activities to services for 0-5 year olds and their families. In comparison, agencies with no involvement in CfC devoted 58 percent to such services.

|

Per cent |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All of it | Most of it | About Half | Some | Very little | Total | |

| Member of CfC Committee | 24 | 17 | 18 | 34 | 7 | 100 |

| Provides services funded under CfC | 36 | 18 | 11 | 28 | 8 | 100 |

| None | 37 | 15 | 6 | 26 | 15 | 100 |

(N = 482)

Note: May not add up to 100% due to rounding

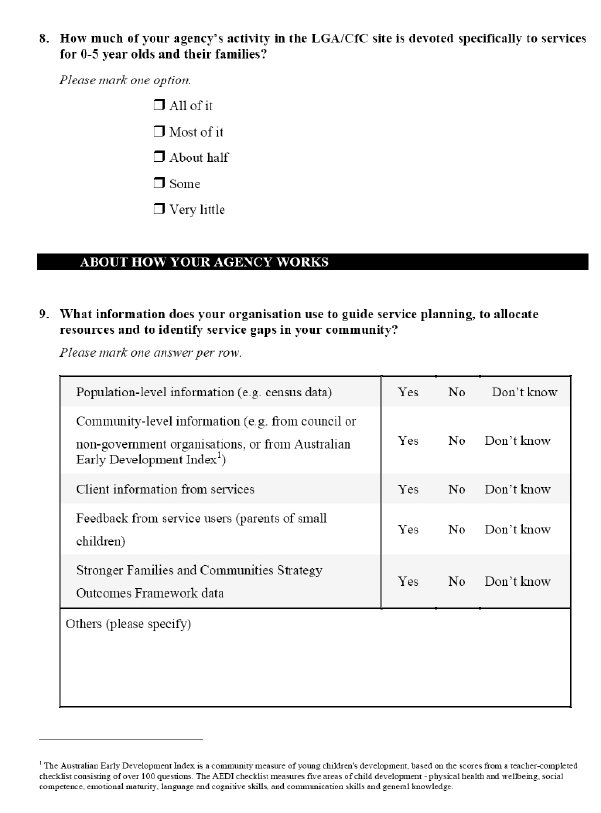

Table 13 shows the extent to which information sources such as the SFCS Outcomes Framework were used as a guide to plan services, allocate resources and identify service gaps in the community. Most services used a variety of information sources, with feedback from service users being the most popular method. More than three quarters of services (76 percent) used service user feedback, followed by client information from services (used by 68 percent), community-level information (62 percent), and population-level information (52 percent).

Relatively few services (28 percent) used SFCS Outcomes Framework data. A fairly high proportion of respondents (16 percent) stated that they did not know whether or not this data was used, perhaps reflecting many respondents' limited involvement with CfC and a lack of communication about the SFCS Outcomes Framework.

|

Per cent |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Don't Know | Missing | Total | |

| Population-level information (e.g. census data) | 52 | 18 | 6 | 24 | 100 |

| Community-level information (e.g. from council or non-govt organisations, or from Australian Early Dev Index) | 62 | 11 | 5 | 22 | 100 |

| Client Information from services | 68 | 7 | 4 | 21 | 100 |

| Feedback from service users (parents of small children) | 76 | 3 | 3 | 18 | 100 |

| SFCS Outcomes Framework data | 28 | 28 | 16 | 29 | 100 |

(N = 482)

Note: May not add up to 100% due to rounding

Table 14 shows the use of SFCS Outcomes Framework data by agencies that have a role in CfC. The results show that 54 percent of agencies involved with CfC used the SFCS Outcomes Framework data, compared with 5 percent of those without any involvement in CfC.

|

Per cent |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Don't Know | Total | |

| Member of Communities for Children Committee | 47 | 31 | 22 | 100 |

| Provides services funded under CfC | 61 | 22 | 18 | 100 |

| None | 5 | 71 | 24 | 100 |

(N = 482)

Note: May not add up to 100% due to rounding

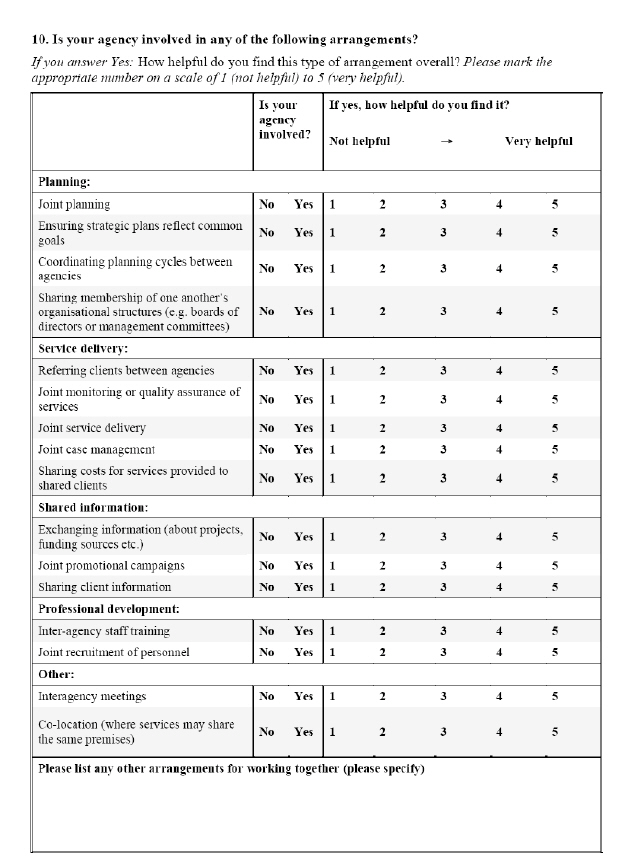

Strategic Level Coordination

The Strategic Level Coordination component of the study was intended to establish the level of interagency cooperation relating to planning, coordinating and commissioning services, and to measure changes during the funding period.

For the purposes of the Snapshot Survey, interagency working and cooperation in the planning, coordinating and commissioning of services was refined into the range of activities shown in Table 15. The activities were grouped into five categories: planning, service delivery, shared information, professional development and other.

Respondents were also asked which interagency activities they believed were most helpful. The helpfulness score was recorded on a scale from 1 (least helpful) to 5 (most helpful), with a midpoint of 3 (neither helpful nor unhelpful).

|

Agency involvement |

Average helpfulness score (from 1 [low] to 5 [high]) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Missing | Total | ||

| Planning: | |||||

| Joint planning | 66 | 27 | 8 | 100 | 4.0 |

| Ensuring strategic plans reflect common goals | 55 | 27 | 19 | 100 | 3.9 |

| Coordinating planning cycles between agencies | 26 | 54 | 20 | 100 | 3.6 |

| Sharing membership of one another's organisational structures (e.g. boards of directors or management committees) |

27 | 54 | 19 | 100 | 3.7 |

| Service delivery: | |||||

| Referring clients between agencies | 82 | 13 | 5 | 100 | 4.1 |

| Joint monitoring or quality assurance of services | 28 | 53 | 19 | 100 | 3.7 |

| Joint service delivery | 60 | 33 | 0 | 100 | 4.0 |

| Joint case management | 44 | 48 | 8 | 100 | 3.9 |

| Sharing costs for services provided to shared clients | 25 | 55 | 19 | 100 | 4.0 |

| Shared information: | |||||

| Exchanging information (about projects, funding sources etc.) | 80 | 14 | 6 | 100 | 4.0 |

| Joint promotional campaigns | 52 | 41 | 8 | 100 | 4.0 |

| Sharing client information | 49 | 43 | 9 | 100 | 3.9 |

| Professional development: | |||||

| Interagency staff training | 53 | 40 | 7 | 100 | 4.1 |

| Joint recruitment of personnel | 16 | 70 | 14 | 100 | 3.9 |

| Other: | |||||

| Interagency meetings | 79 | 17 | 4 | 100 | 4.0 |

| Co-location (where services may share the same premises) | 41 | 51 | 8 | 100 | 4.0 |

Note: May not add up to 100% due to rounding

As Table 15 shows, each of the interagency activities listed was performed by at least some agencies. The interagency activities with which agencies were most commonly involved were:

- Referring clients between agencies (82per cent);

- Exchanging information (about projects, funding sources, etcetera) (80 per cent);

- Interagency meetings (79 per cent);

- Joint planning (66 per cent); and

- Joint service delivery (60 per cent).

Respondents believed that the following interagency activities were the most helpful:

- Referring clients between agencies (4.1);

- Interagency staff training (4.1);

- Joint service delivery (4.0);

- Exchanging information (about projects, funding sources etcetera.) (4.0); and

- Co-location (where services may share the same premises) (4.0).

Three interagency activities - referral of clients between agencies, the exchange of information, and joint service delivery - were among the most common interagency activities and were, at the same time, seen to be among the most helpful.

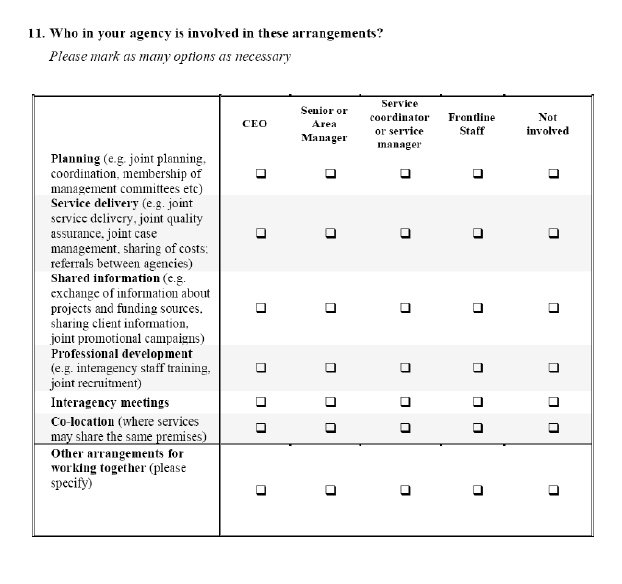

Table 16 shows the positions of staff involved in interagency arrangements. Most commonly, staff close to the ground level of service delivery - service coordinators/managers and frontline staff - were the ones carrying out interagency activities. For example, 33 per cent of frontline staff and 29 per cent of service coordinators/ managers collaborated with other agencies when delivering services. By contrast, senior staff - CEOs and senior or area managers - were significantly less involved in interagency arrangements.

|

Per cent |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEO | Senior or Area Manager |

Service coordinator or service manager |

Frontline Staff |

Not Involved |

Missing | Total | |

| Planning (e.g. joint planning, coordination, membership of management committees etc.) | 11 | 20 | 28 | 21 | 9 | 11 | 100 |

| Service delivery (e.g. joint service delivery, joint quality assurance, joint case management, sharing of costs; referrals between agencies) | 5 | 12 | 29 | 33 | 10 | 12 | 100 |

| Shared information (e.g. exchange of information about projects and funding sources, sharing client information, joint promotional campaigns) | 9 | 17 | 31 | 28 | 6 | 10 | 100 |

| Professional development (e.g. interagency staff training, joint recruitment) | 7 | 15 | 27 | 26 | 14 | 12 | 100 |

| Interagency meetings | 9 | 17 | 31 | 27 | 7 | 10 | 100 |

| Co-location (where services may share the same premises) | 6 | 11 | 20 | 19 | 27 | 16 | 100 |

(N = 482)

Note: May not add up to 100% due to rounding

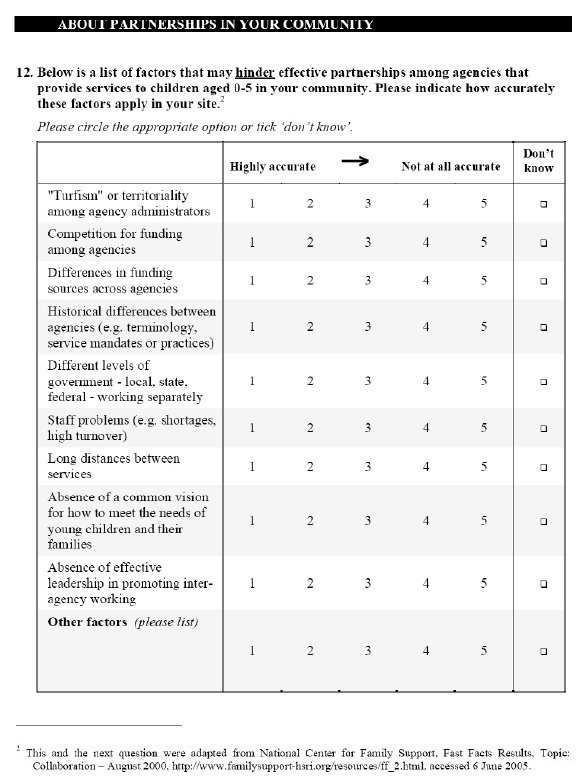

Factors that could hinder effective partnerships and barriers to service coordination are presented in Table 17. Respondents were asked to rank a number of statements relating to partnerships in their site on a scale from 1 (not all accurate) to 5 (highly accurate). In other words, the higher the score, the more a statement was seen to be a hindrance to cooperation.

| Scale: 1 to 5 |

Per cent |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Score | Don't know | Missing | Total | |

| 'Turfism' or territoriality among agency administrators | 2.8 | 17 | 17 | 100 |

| Competition for funding among agencies | 3.3 | 16 | 17 | 100 |

| Differences in funding sources across agencies | 3.5 | 18 | 17 | 100 |

| Historical differences between agencies (e.g. terminology, service mandates or practices) | 3.2 | 18 | 17 | 100 |

| Different levels of government - local, state, federal - working separately | 3.5 | 10 | 17 | 100 |

| Staff problems (e.g. shortages, high turnover) | 3.4 | 9 | 17 | 100 |

| Long distances between services | 2.7 | 10 | 18 | 100 |

| Absence of a common vision for how to meet the needs of young children and their families | 2.6 | 8 | 18 | 100 |

| Absence of effective leadership in promoting interagency working | 2.8 | 13 | 17 | 100 |

(N = 482)

Note: May not add up to 100% due to rounding

Respondents believed the following factors were most likely to hinder effective partnerships:

- Differences in funding sources across agencies (3.5);

- Different levels of government (local, state, federal) working separately (3.5);

- Staff problems (e.g. shortages, high turnover) (3.4); and

- Competition for funding among agencies (3.3).

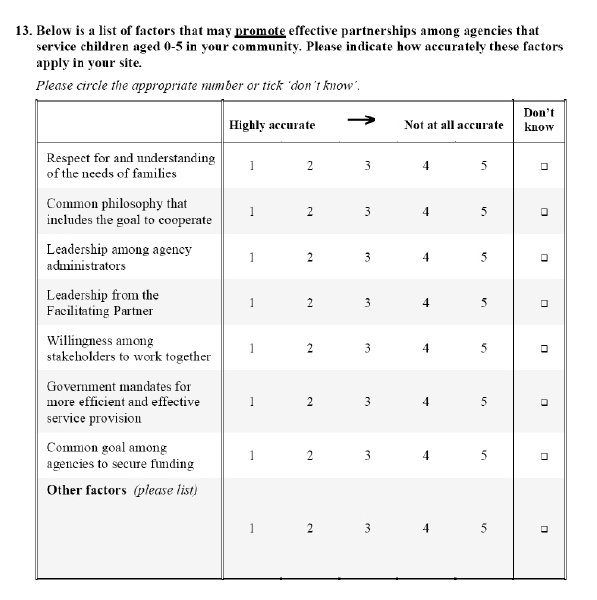

The factors that are likely to promote effective partnerships and facilitate better coordination are presented in Table 18. In a similar manner to the previous question, respondents were asked to rank a number of statements relating to partnerships in their site on a scale from 1 (not at all accurate) to 5 (highly accurate). In other words, the higher the score, the more is a statement seen to be promoting cooperation.

| Scale: 1 to 5 |

Per cent |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Score | Don't know | Missing | Total | |

| Respect for and understanding of the needs of families | 4.3 | 2 | 16 | 100 |

| Common philosophy that includes the goal to cooperate | 4.0 | 4 | 17 | 100 |

| Leadership among agency administrators | 3.8 | 7 | 18 | 100 |

| Leadership from the Facilitating Partner | 3.9 | 13 | 18 | 100 |

| Willingness among stakeholders to work together | 4.1 | 4 | 17 | 100 |

| Government mandates for more efficient and effective service provision | 3.4 | 11 | 17 | 100 |

| Common goal among agencies to secure funding | 3.5 | 12 | 17 | 100 |

(N = 482)

Note: May not add up to 100% due to rounding

From the results in Table 18, respondents thought that the following factors were most likely to promote effective partnerships:

- Respect for and understanding of the needs of families (4.3);

- Willingness among stakeholders to work together (4.1);

- Common philosophy that includes the goal to cooperate (4.0)

- Leadership from the Facilitating Partner (3.9); and

- Leadership among agency administrators (3.8).

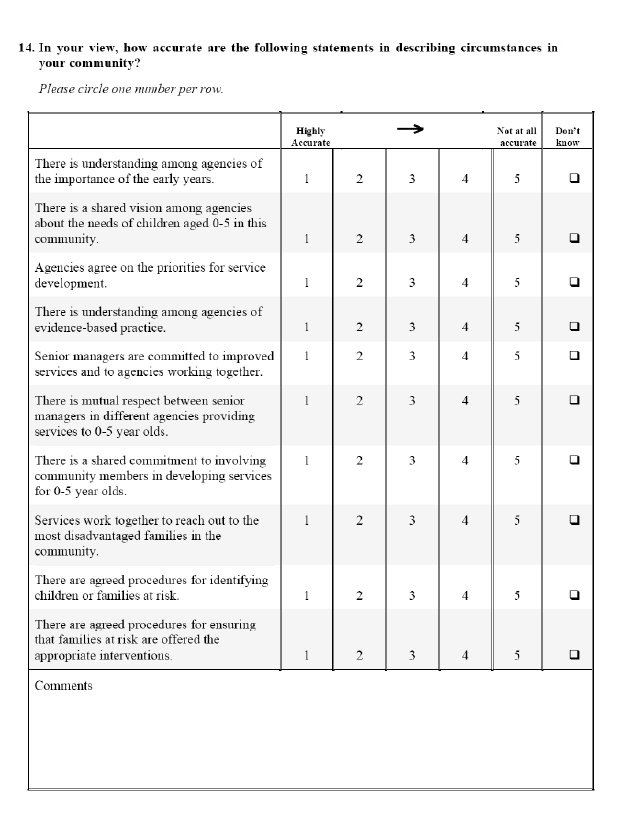

Respondents were asked to rate the accuracy of statements regarding the commitment of local agencies to work together for the benefit of young children in their communities on a scale form 1 (not at all accurate) to 5 (highly accurate). Results are presented in Table 19. The higher the score, the more a particular attitude or procedure was seen to be an accurate description of local agencies. Overall, respondents reported that there was a good understanding of the importance of the early years (4.2). Respondents moderately agreed that there is a shared vision about the needs of children aged 0-5 in their agencies, that 'senior managers are committed to improved services and to agencies working together' (both 3.6) and that there is a 'shared commitment to involving community members in developing services for 0-5 year olds' (3.5). Attitudes and procedures which were reportedly least prevalent in the communities were 'agreement on the priorities for service development' and 'agreed procedures for identifying children or families at risk' (both 3.2), and 'agreed procedures for ensuring that families are offered appropriate interventions' (3.1).

| Scale: 1 to 5 |

Per cent |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Score | Don't know | Missing | Total | |

| There is understanding among agencies of the importance of the early years. | 4.2 | 3 | 15 | 100 |

| There is a shared vision among agencies about the needs of children aged 0-5 in this community. | 3.6 | 6 | 15 | 100 |

| Agencies agree on the priorities for service development. | 3.2 | 13 | 16 | 100 |

| There is understanding among agencies of evidence-based practice. | 3.4 | 14 | 15 | 100 |

| Senior managers are committed to improved services and to agencies working together. | 3.6 | 11 | 15 | 100 |

| There is mutual respect between senior managers in different agencies providing services to 0-5 year olds. | 3.7 | 16 | 16 | 100 |

| There is a shared commitment to involving community members in developing services for 0-5 year olds. | 3.5 | 9 | 15 | 100 |

| Services work together to reach out to the most disadvantaged families in the community. | 3.4 | 6 | 16 | 100 |

| There are agreed procedures for identifying children or families at risk. | 3.2 | 13 | 15 | 100 |

| There are agreed procedures for ensuring that families at risk are offered the appropriate interventions. | 3.1 | 13 | 16 | 100 |

(N = 482)

Note: May not add up to 100% due to rounding

Operational Level Coordination

The Operational Level component of the service coordination study addressed how services worked together in practice. It measured how well services were collaborating, whether they knew about each other and whether services found it easy to refer to one another. The Operational Level Coordination component also investigated whether or not protocols existed for sharing information between agencies.

Respondents had a relatively high level of awareness of the services available to 0-5 year olds and their families in their community (Table 20). Almost two-thirds of respondents believed that they were either fully or mostly aware of the full range of services.

| Yes, fully | Mostly | Somewhat | Not really | Not at all | Missing | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per cent | 16 | 44 | 17 | 9 | 1 | 13 | 100 |

(N = 482)

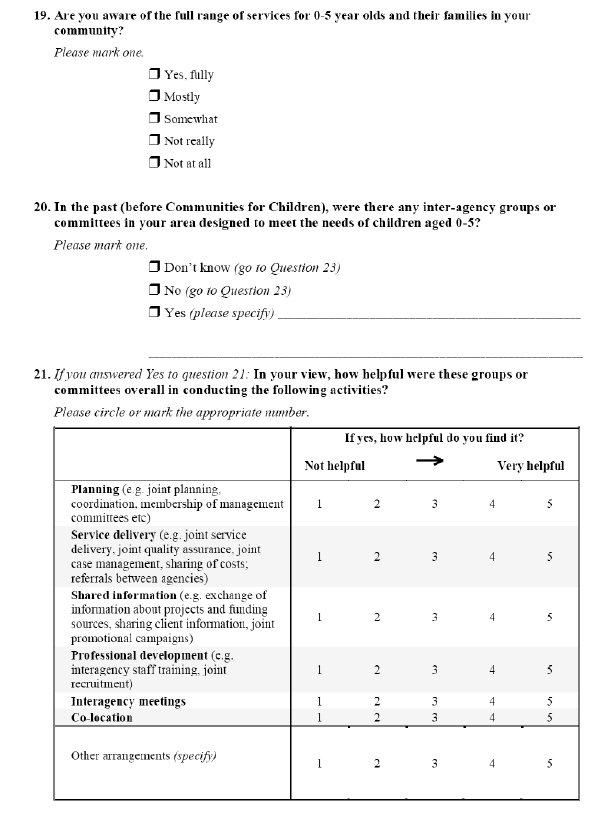

Pre-existing interagency groups or committees

The survey investigated whether any relevant cooperative structures among agencies existed in the sites before CfC. Table 21 shows that 39 per cent of respondents knew of interagency groups designed to meet the needs of children aged 0-5 years in their area before CfC was established. A further 35 per cent of respondents did not know whether any such groups were in existence before the establishment of CfC. Only 12 per cent could definitely assert that there were no interagency groups prior to the establishment of CfC.

| Per cent | |

|---|---|

| Yes | 39 |

| No | 12 |

| Don't know | 35 |

| Missing | 14 |

| Total | 100 |

(N = 482)

Respondents were asked to rank how helpful they believed interagency groups or committees were in conducting a range of joint agency arrangements (Table 22). Possible answers ranged from very helpful (1) to not helpful at all (5). This question had a very high non-response rate, perhaps reflecting many respondents' limited knowledge of interagency groups and the difficulty of assessing the impact that past groups may have had. Those who did respond found interagency groups that pre-dated CfC to be moderately helpful in all aspects of working together, especially in sharing information and interagency meetings (3.7 and 3.6 out of 5 respectively).

| (Range: 1 to 5) | Per cent | |

|---|---|---|

| Helpfulness of pre-CfC interagency groups or committee |

Non-response | |

| Planning (e.g. joint planning; coordination; membership of management committees etc.) | 3.4 | 72 |

| Service delivery (e.g. joint service delivery; joint quality assurance; joint case management; sharing of costs; referrals between agencies) | 3.2 | 72 |

| Shared information (e.g. exchange of information about projects and funding sources; sharing client information; joint promotional campaigns) | 3.7 | 71 |

| Professional development (e.g. interagency staff training; joint recruitment) | 3.2 | 73 |

| Interagency meetings | 3.6 | 72 |

| Co-location | 3.0 | 77 |

(N= 482)

| Staff from different services work closely together most of the time | Staff from different services work closely together occasionally | Staff from different services know little about each other's work | Missing | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per cent | 29 | 41 | 14 | 17 | 100 |

(N = 482)

Note: May not add up to 100% due to rounding

Table 23 shows that only 14 per cent of staff from different services had little knowledge about each other's work. Almost 30 per cent of respondents said that their service worked closely with staff from other services most of the time and 41 per cent said that staff from different services occasionally worked closely together.

| A well coordinated team of services | A partially coordinated team of services | A group of separate, uncoordinated services | Missing | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per cent | 12 | 58 | 16 | 14 | 100 |

(N = 482)