In the Best Interests of Children - Reforming the Child Support Scheme - Report of the Ministerial Taskforce on Child Support

- PART A: Overview

- PART B: Background and Analysis

- PART C: Detailed Recommendations

- PART D: Conclusion

Letter of transmittal

Ministerial Taskforce on Child Support

The Hon Senator Kay Patterson

Minister for Family and Community Services

Parliament House

Canberra ACT 2600

Dear Minister

I am please to be able to present to you the Report of the Ministerial Taskforce on Child Support.

After intensive and wide-ranging new research, and consultation with a range of stakeholders, the Taskforce is recommending fundamental changes to the way in which child support obligations are assessed. It is also recommending a number of changes to the way the formula is administered, within the ambit of the Terms of Reference.

The motivation for these changes is based on findings that the current scheme:

- Does not reflect current community standards, particularly in relation to the sharing of parenting by fathers and increasing workforce participation of mothers;

- Does not accurately reflect the relationship between income and spending on children in ordinary families; and

- It is not well integrated, in significant respects, with the income support and family payments systems, nor with the system of family law.

The Taskforce has endeavoured to develop a new approach that is better informed by evidence, better integrated, and more transparently fair to both parents, and that focuses on the needs of children.

The report explains in detail the approach and research methods taken by the Taskforce and the underlying principals and reasoning for the Recommendations made. It contains detailed cameos of disposable family incomes under the proposed and existing schemes, modelling of population impacts of the proposed scheme and a series of original research papers.

The Taskforce has developed its recommendations as an integrated package of measure where each component has been carefully considered and balanced against every other component. It is my hope that the Government will consider them in that light.

Yours sincerely

Patrick Parkinson

Chairperson

Ministerial Taskforce on child Support

3 June 2005

The Taskforce would like to place on record its appreciation for the outstanding support so willingly provided by the staff of the Department of Family and Community Services (FaCS) and other departments and agencies.

Valuable assistance was provided from right across FaCS, including the Family Relationship Services and Child Support Policy Branch, the Family Payments Branch, the Research and Data Management Branch and the Ministerial, Media and Executive Support Branch.

The Secretariat to the Taskforce was drawn from within FaCS, and a wide array of staff played a part in the Secretariat in the course of the Taskforce’s investigations. The leadership provided by Tony Carmichael (Assistant Secretary, Family Relationship Services and Child Support Policy Branch) and Robyn Seth-Purdie (Director, Child Support Policy) in the course of this exercise and their enthusiasm and commitment has been especially appreciated. The Taskforce would also like to thank Kirsten Anker, Allison Barnes, Dominic Comparelli, Greg Dare, Michael Fuery, Natalee Gersbach, Emma Hall, Rose-Marie Hamood, Andrew Herscovitch, John Olejniczak, Rebecca Pietsch, Anne Pulford, Anna Ritson, Amanda Robertson, Val Ridley, and Mira Zivkovic.

Responsibility for the content of the Report and the associated recommendations rests, of course, with the Taskforce.

PART A: Overview

Background to the review

The registration and collection aspects of the Child Support Scheme were introduced in 1988, and the formula for assessment in 1989. The formula for assessing child support was based upon recommendations of a Consultative Group chaired by Justice John Fogarty of the Family Court, which reported in 1988. The current Scheme grew out of concerns about the effects of marriage breakdown on the living standards of children, especially those living in sole-parent households with their mothers. There was also concern about the increase in the numbers of separated parents dependent on welfare; low amounts of child support being paid by non-custodial parents; and the difficulties in updating and enforcing child maintenance obligations through the courts.

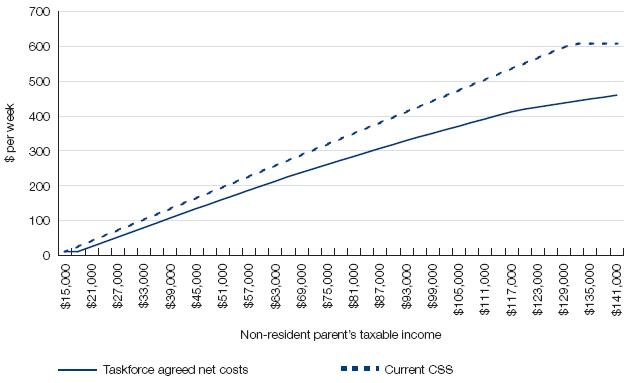

Although there have been numerous modifications to the formula over the years, the fundamentals remain unchanged. The basic formula under the Scheme requires liable parents to pay a percentage of their taxable income after a self-support component is deducted ($13 462 for a single non-resident parent in 2005). The percentages are 18 per cent for one child, 27 per cent for two children, 32 per cent for three children, 34 per cent for four children, and 36 per cent for five or more children. The formula reduces the liability of the non-resident parent where the income of the resident parent exceeds the level of average weekly earnings for all employees (currently $39 312). The Scheme also provides for departure from the formula on a limited number of grounds through a process called Change of Assessment.

To a considerable extent, the Child Support Scheme has achieved the objectives that successive governments have given for it. The Scheme has also been successful in promoting community acceptance of the idea of child support obligations. However, much has changed in the circumstances of Australian families since 1988. There is now a greatly increased emphasis on shared parental responsibility, and the importance of both parents remaining actively involved in their children’s lives after separation has gained much greater recognition. Child support policy can no longer just be concerned with enforcing the financial obligations of reluctant non-resident parents. Ensuring the payment of child support is one part of a bigger picture of encouraging the continuing involvement of both parents in the upbringing of their children.

There have also been other kinds of change that affect child support policy. Since the late 1980s, there has been a substantial increase in the workforce participation of mothers, particularly through part-time employment. Children in intact families tend to be supported from the incomes of both parents. The Government is refocussing its income support and work participation policies to treat both parents as potential labour force participants with the aims of improving family wellbeing over the longer term and reducing welfare dependence.

It is against the background of all these changes since the late 1980s, as well as the ongoing public concern about aspects of the Child Support Scheme, that this review has taken place. This review was initiated in response to the House of Representatives Committee on Family and Community Affairs report on child custody arrangements in the event of family separation (Every Picture Tells a Story, December 2003). It recommended that a ministerial taskforce be established to examine the child support formula. The Prime Minister announced the Government’s acceptance of this recommendation on 29 July 2004 and the Taskforce, aided by a Reference Group, began its work shortly thereafter. Members of the Taskforce had expertise in one or more of: social and economic policy, family law, family policy, and the costs of children. Membership of the Reference Group was drawn from advocacy groups representing child support payers and payees, and also included professionals who have experience in issues concerning parenting after separation, relationship mediation and counselling, and social policy.

Terms of Reference

The Terms of Reference provide that the Taskforce, supported by the Reference Group, will:

>

- Provide advice around the short-term recommendations of the Committee along the lines of those set out in the Report (Recommendation 25) that relate to:

- increasing the minimum child support liability;

- lowering the ‘cap’ on the assessed income of parents;

- changing the link between the child support payments and the time children spend with each parent; and

- the treatment of any overtime income and income from a second job.

- Evaluate the existing formula percentages and associated exempt and disregarded incomes, having regard to the findings of the Report and the available or commissioned research including:

- data on the costs of children in separated households at different income levels, including the costs for both parents to maintain significant and meaningful contact with their children;

- the costs for both parents of re-establishing homes for their children and themselves after separation; and

- advise on what research program is necessary to provide an ongoing basis for monitoring the child support formula.

- Consider how the Child Support Scheme can play a role in encouraging couples to reach agreement about parenting arrangements.

- Consider how Family Relationship Centres may contribute to the understanding of and compliance with the Child Support Scheme.

Approach of the Taskforce

In order to meet the Terms of Reference, the Taskforce:

- analysed the submissions on child support made to the House of Representatives Committee on Family and Community Affairs in 2003;

- analysed issues raised in Ministerial correspondence and unsolicited submissions to the Taskforce;

- consulted the Reference Group on issues to be considered;

- reviewed the research on the costs of children both in Australia and overseas;

- conducted new research on the costs of children using three different approaches;

- examined the current impact of the Scheme on the living standards of both resident and non-resident parents;

- examined the child support systems of other countries and in particular, new approaches to child support since Australia developed its Scheme;

- consulted overseas experts on child support;

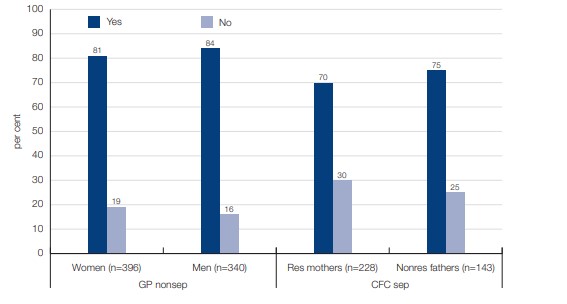

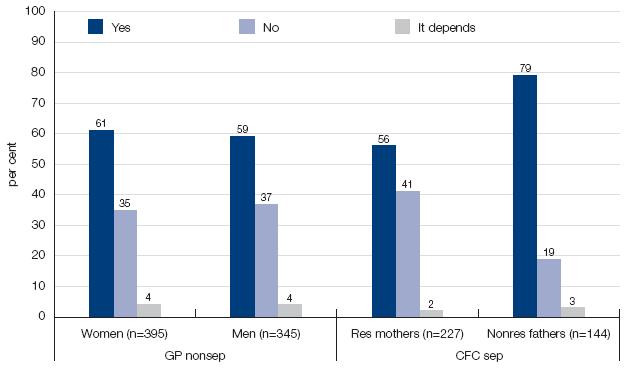

- commissioned the Australian Institute of Family Studies to conduct a survey of community attitudes towards child support;

- considered the interaction of the Child Support Scheme with Family Tax Benefit (FTB) and income support payments;

- consulted the Reference Group and other stakeholders on proposals for change;

- tested the proposals using a computer model that examined their impact for a range of different families; and

- consulted the Child Support Agency on the feasibility of implementing the proposed new approach.

Papers containing the research underpinning the Taskforce’s findings are published in Volume 2 of the Report.

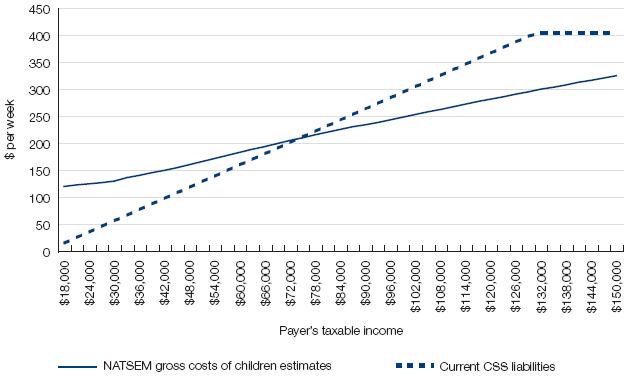

A major part of the work of the Taskforce required the analysis of the operation of the existing Child Support Scheme and proposed alternatives and their interaction with the tax and income support systems. The National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling (NATSEM) at the University of Canberra was commissioned to develop a detailed model for this purpose. This was a complex task, but this microsimulation model and the extension of NATSEM’s population model (STINMOD) provide invaluable tools for future policy analysis and development. They enable the modelling of alternative policies to show outcomes for both individual families and the general population.

A new child support formula for Australia

A formula-based approach to assessing child support is administratively straightforward, transparent and efficient by comparison with more discretionary alternatives, such as relying on the courts. It provides the mechanism for the costs of children to be distributed equitably in accordance with the parents’ capacities to pay. Its outcomes are more predictable. Its administration is also more efficient and cost-effective.

However, any child support formula that is assessed administratively represents a series of compromises between competing objectives—including fairness, simplicity and cost-effectiveness. What an administrative formula offers in terms of simplicity and speed of assessment, it may lack in capacity to adjust to the individual circumstances of all parties affected by it.

There are many factors that need to be taken into account in a child support formula. These include the economies of scale that apply in families with different numbers of children, or with children of different ages or gender, how income of the resident parent should be taken into account, how opportunity costs and childcare expenses should be treated, and how shared care should affect child support obligations. Such issues remain matters for judgment using the best available evidence.

In undertaking the review, the central concern of the Taskforce was the wellbeing of children after separation. However, the Taskforce also recognised the importance of balancing the interests of the parents and ensuring that the fundamental principles of the Scheme reflect community values about child support in Australia.

The basis for calculating child support obligations

Although a number of different factors were considered by the Consultative Group that proposed the formula in 1988, its starting point was that, wherever possible, children should enjoy the benefit of a similar proportion of the income of each parent to that which they would have enjoyed if their parents lived together. This includes not only the proportion of income spent on consumables such as food, but a proportion of the costs of all goods shared by members of the household, such as housing, running a car, and fuel bills.

This is known as the ‘continuity of expenditure’ principle. It has been the basis not only of the Australian Scheme but of many others around the world. It does not mean that children will necessarily be able to maintain the same living standards after their parents’ separation as they enjoyed before. Children’s living standards depend on the overall income of the households in which they spend their time. However, the Consultative Group considered that this principle was the best starting point for calculating an appropriate level of child support.

The Child Support Taskforce agrees that this remains the fairest basis on which to calculate child support. While the standard of living of many resident parents falls after separation, this loss in living standards may be ameliorated if they remarry, form stable de facto relationships, or manage to increase their workforce participation. The child support formula needs to apply generally until the children are 18 and the circumstances of parents can change considerably over this time. Part VIII of the Family Law Act 1975 gives the courts wide-ranging powers to divide the property of parents, and the financial needs of the children’s primary caregiver following separation are an important factor that courts consider. They also have the power to award spousal maintenance in appropriate cases. Certain powers to alter interests in property and to award maintenance also exist under State and Territory laws concerning de facto relationships. Government benefits such as Parenting Payment, the provision of Family Tax Benefit (FTB) B for sole parents, Rent Assistance, special health care benefits and the Pensioner Concession Card also help cushion the effects of separation for parents.

The child support formula should provide a transparently fair basis for calculating child support. This requirement cannot be met if the Scheme aims to fulfil objectives other than sharing the costs of children equitably between the parents. For that reason, it is proper that child support obligations be based on the best available evidence of how much children cost to parents with different levels of combined household income.

The costs of children in separated households

The Taskforce was asked to consider the costs of children in separated households. Where there is regular contact between children and non-resident parents, the costs of children increase significantly because of the duplicated infrastructure costs of running two households. These costs include housing, furnishings and motor vehicles, the loss of economies of scale in the one household in terms of energy costs and other shared expenses, and the costs involved in exercising contact, especially transportation.

Both parents are likely to experience at least part of these increased costs of raising children if the children are spending significant amounts of time with both of them. How those additional costs are distributed between the parents depends on a number of different factors, including the division of property when the parents separate, and the transport arrangements for contact visits. The Taskforce has taken account of this research in its recommendations on how to factor the costs of contact into the formula.

Issues with the current formula

While the Child Support Taskforce agrees that the ‘continuity of expenditure’ principle remains the best starting point for considering an appropriate level of child support, it considers that the current formula is no longer appropriate as the basis for child support liabilities in 2005—for the following reasons.

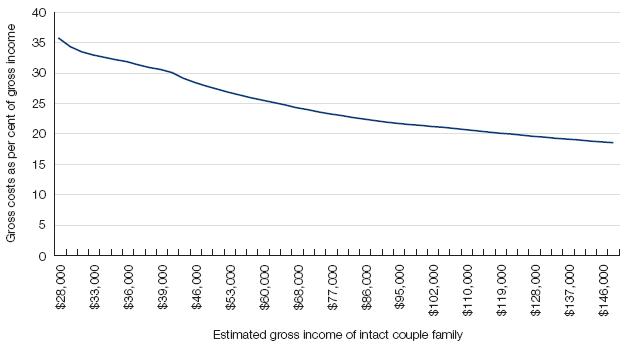

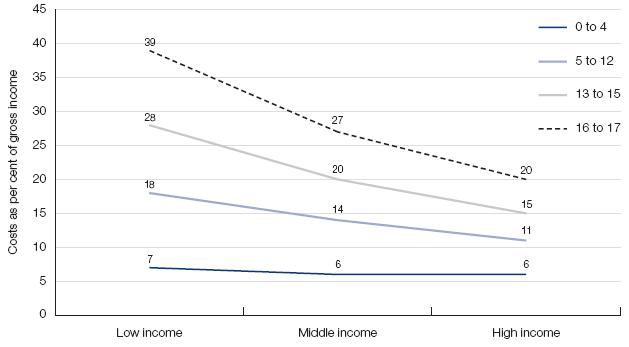

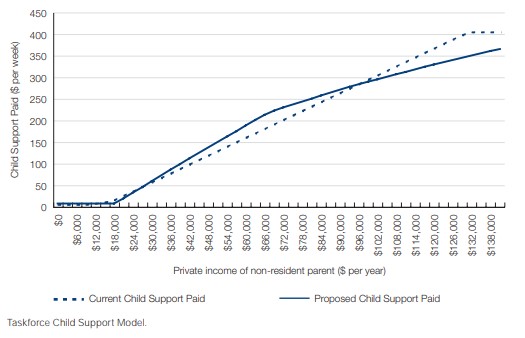

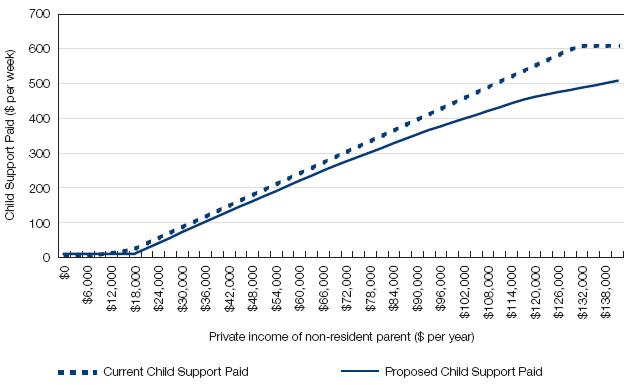

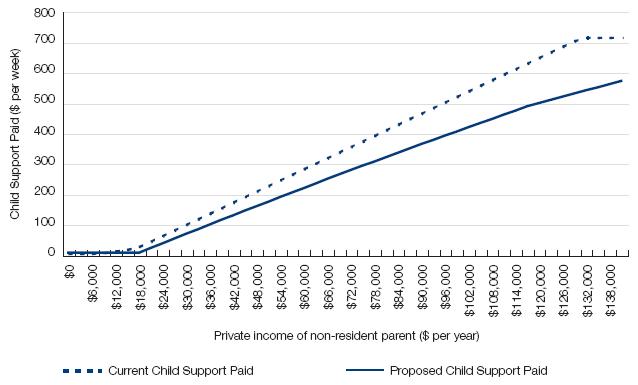

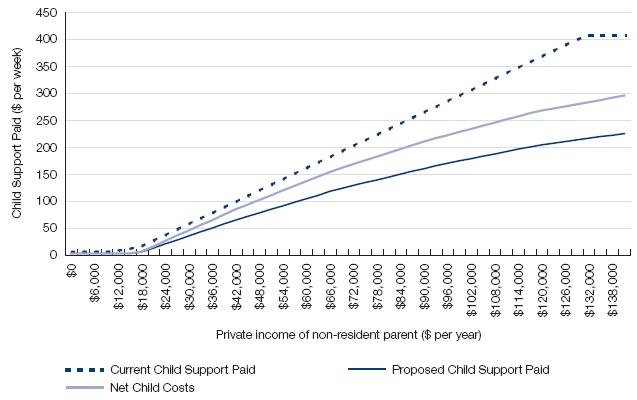

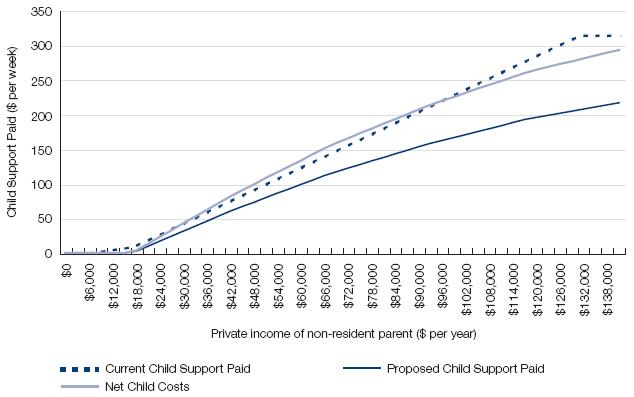

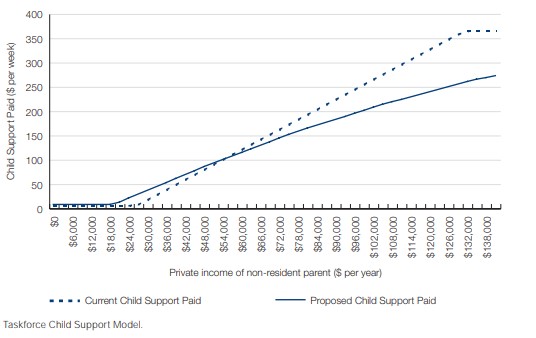

Fixed percentages

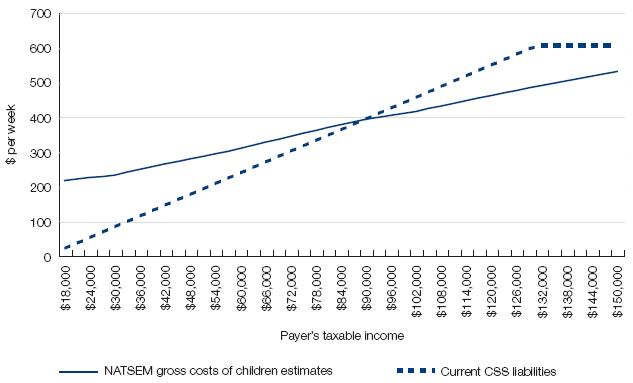

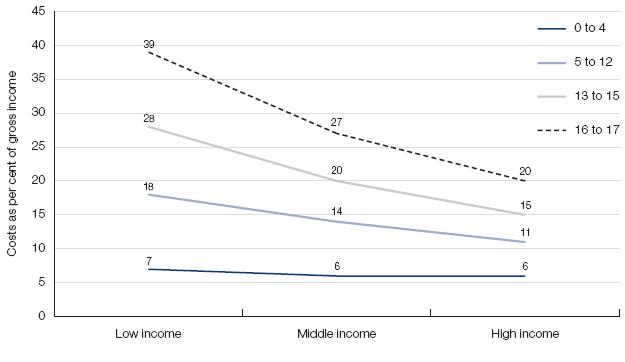

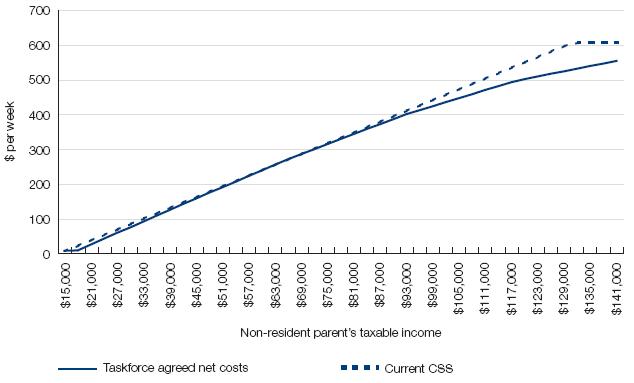

- The formula assumes that, across the income range, people spend the same proportion of their income on children. This justifies the fixed percentages above the self-support component based on the number of children being supported. However, the research of the Taskforce, and the preponderance of international research published since 1988, shows that, while the higher the household income, the more parents spend on their children in dollar figures, expenditure declines as a percentage of their income. The impact of marginal tax rates is one reason that spending on children does not increase in proportion to the increases in people’s taxable income. Furthermore, as income increases, expenditure becomes more discretionary. Parents who are already providing a comfortable standard of living for their children may choose to put more money into savings or to spend additional income in ways other than on their children.

These research findings make it difficult to justify the fixed percentages of taxable income under the present Scheme. At the higher ends of the income spectrum, the current child support liability is well in excess of levels of expenditure on children in comparable intact families, especially for one or two children under 13 years of age.

Set percentages, irrespective of age

- The current formula applies the same percentage of income irrespective of the age of the children and therefore is not sensitive to the difference in the costs of children as they grow older. Research suggests that expenditure on teenagers is two to three times as high as for younger children, and this pattern prevails at every income level. While the approach of averaging the costs of children over the entire age range has the merit of simplicity, it means that child support payments are likely to be inadequate at the time that the costs of children are at their highest, and too high when the children are younger.

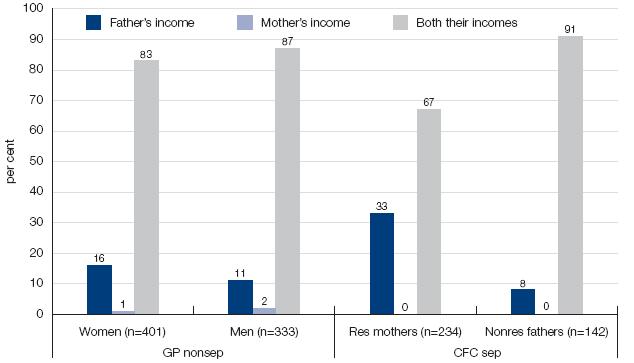

The need to reflect two incomes

- The substantial increase in the part-time employment of women with children since the Scheme was introduced means that a majority of intact families with children depend on two incomes. The formula, however, is based only on the non-resident parent’s income for the great majority of families, since the resident parent’s income is only factored in above the threshold of average weekly earnings for all employees. It is therefore not obvious to child support payers that both parents are sharing in the cost of supporting their children according to their capacity.

Children of second families

- The way in which children of second families are taken into account under the current formula is of significant benefit to low-income non-resident parents but does not provide much relief for those on higher incomes who have new children to support. This is because payers with new biological children are given a dollar-figure increase in their exempt income before the relevant percentage is applied. This does not reflect the reality that expenditure on children increases with household income. For low-income payers, this figure represents a large increase as a percentage of their income, but it is proportionally only a small increase for higher-income payers. At both ends of the income spectrum, this results in unequal treatment of the children of the non-resident parent, as the amount allowed for the support of the new children may be much higher or much lower than the likely costs of the new children, and has unjustifiable effects on the level of the payer’s liability to the child support children. In some cases, the increased exempt amount may have the effect of reducing the payer’s child support obligation to a minimal level.

A new approach to the calculation of child support

To address these problems, the Taskforce proposes a fundamental change to the Child Support Scheme.

The essential feature of the proposed new Scheme is that the costs of children are first worked out based upon the parents’ combined income, with those costs then distributed between the mother and the father in accordance with their respective shares of that combined income and levels of contact (see section Taking account of regular contact and shared care). The resident parent is expected to incur his or her share of the cost in the course of caring for the child. The non-resident parent pays his or her share in the form of child support. Both parents will have a component for their self-support deducted from their income in working out their Child Support Income.

This gives practical expression to the first objective of the Scheme, that parents share in the cost of supporting their children according to their capacity. The proposed Scheme is based upon the ‘income shares’ approach utilised in many other jurisdictions and reflects the notion of shared parental responsibility contained in Part VII of the Family Law Act 1975.

Assessing the costs of children

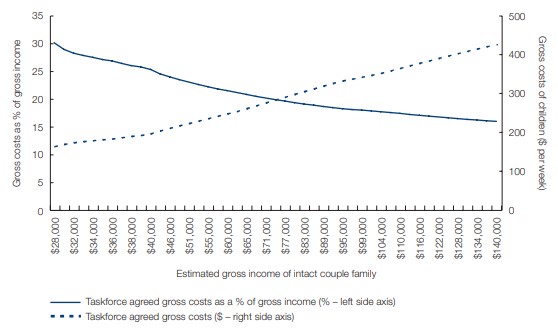

There is no ‘fixed cost’ of children. The costs of children vary in accordance with the level of income of the parents. Estimates of the cost of raising children are therefore based upon evidence about patterns of expenditure on children, or the amount of money that is needed to attain a particular standard of living.

Three approaches to estimating the costs of children

The Child Support Taskforce used three different methodologies to reach the best and most up-to-date estimates possible of the costs of children in intact Australian families. The Household Expenditure Survey was used to examine actual patterns of expenditure on children. The Budget Standards approach was used to assess how much parents would need to spend to give children a specific standard of living, taking account of differences in housing costs all over Australia. A study was also done of all previous Australian research on the costs of children, so that the outcomes of these two studies could be compared with previous research findings. The Australian estimates were also benchmarked against international studies on the costs of children. Ultimately, the Taskforce made a considered judgment about the best estimates of the costs of children.

Research on the costs of children can only provide a broad estimate. For example, because it includes a proportion of the housing costs incurred by the family, the costs of children will vary depending on the location of the family. The costs of raising children are therefore much higher in most capital cities than in small regional centres or country areas. While the Taskforce considered housing costs in different locations, it was necessary to average out the housing costs for the purpose of the child support formula. The averages also take no account of the gender mix of children. There are likely to be greater economies of scale in a family with two children of the same gender than if the family has a boy and a girl.

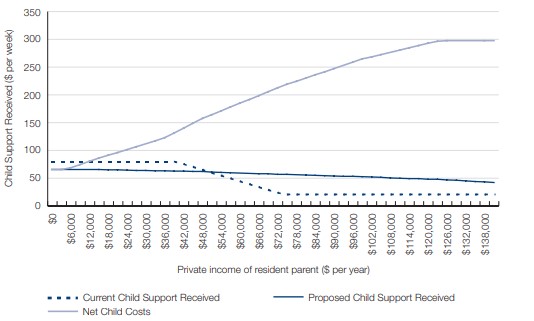

Taking account of government contributions towards the costs of children

Estimates of the gross costs of children are based upon total household income, including government benefits. In order to assess how much the parents spend of their own incomes on children, it is therefore necessary to take account of those benefits.

Raising children in intact families is a partnership of both parents and the government. The government assists most families with the costs of children, especially through FTB A, which is paid on a per child basis. For lower-income families in particular, it provides substantial tax-free financial assistance. In order to work out the amount that it would be reasonable to expect a non-resident parent to pay in child support, it was therefore necessary for the Taskforce to take account of the FTB A that is paid to parents in an intact family at different income levels.

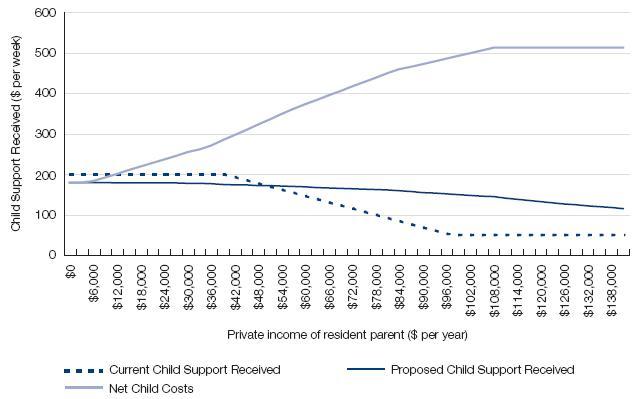

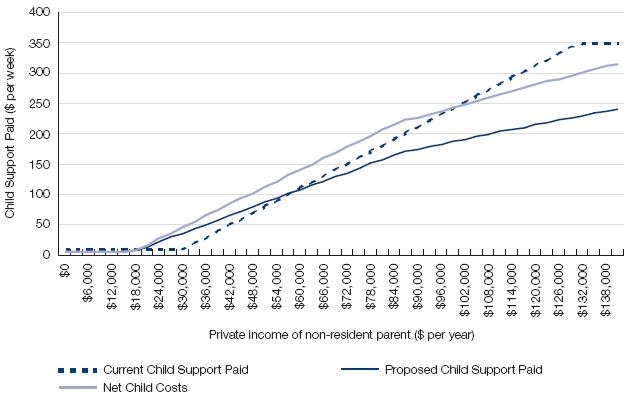

The estimates of the costs of children, less the amount of FTB A in an intact family at that level of household income, gave the Taskforce an estimate of the ‘net costs’ of children in intact families. Its recommendations concerning the level of child support that ought to be paid are based as far as possible on these estimates of the net costs of children.

Taking account of childcare costs

In order to take account of the costs of childcare or income forgone by being out of the workforce to care for young children, the costs of children aged 0–12 have been based upon the research evidence on the costs of 5–12 year-old children. These are substantially higher than the costs of children 0–4. Where childcare costs are particularly high, as they are in some parts of the country, the parent incurring this cost will be able to apply for a change of assessment to help meet this cost. This is an existing ground for a change of assessment under the Scheme.

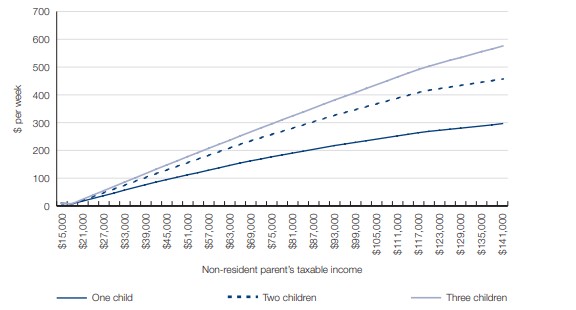

A Costs of Children table not based upon fixed percentages of income

In the proposed new formula the costs of children should be expressed in a Costs of Children table (see Table A of this report) based upon the parents’ combined Child Support Income in two age bands, 0–12 and 13–17. This division reflects the fact that expenditure on teenagers is generally much higher than for younger children. Where there are children in different age bands in the one family, the costs of the children should be the average of the amounts applicable in each band, as expressed in Table A: Costs of Children.

However, these costs will not be expressed as fixed percentages across the entire income range. Since parents spend a higher amount on children the more money they have, but spend less as a percentage of their household income in the higher income ranges, the percentages applicable in this formula gradually decline as combined taxable income increases.

As a consequence, under the new Scheme a liable parent with a high income will pay much more in child support than a parent on a low income, but less as a percentage of his or her taxable income than the parent on a low income. Similarly, where the resident parent is earning a sufficient amount that the combined Child Support Income of the parents takes them into a higher bracket, then her or his income will reduce the amount that the non-resident parent has to pay. It will do so in a much more graduated way than under the current formula, which reduces liabilities more rapidly than is justified by the research on the costs of children. Under the proposed formula, child support obligations will be based upon the relative difference between the parents’ respective incomes.

As household income levels rise far above the community average, it becomes difficult to measure further increases in expenditure on children, and spending becomes increasingly discretionary. The Taskforce has recommended that the costs of children be capped at a combined Child Support Income of 2.5 times MTAWE (male total average weekly earnings, as reported by the Australian Bureau of Statistics). Where both parents have adjusted taxable income over the self-support threshold, this equates to a projected maximum combined income for 2005–06 of $160 386. As at present, this cap can be exceeded through the change of assessment process. The most likely situation for this would be to deal with very high private school fees. All other thresholds are expressed as a proportion of MTAWE above the self-support amounts, so that the formula is indexed annually.

The Taskforce gave consideration to the commonly advocated idea that child support should be based on after-tax income - but rejected this for a range of reasons, as previous inquiries have done. However, the recommendation that the Child Support Scheme should not be based on fixed percentages of income takes account of the impact of taxation in a different way. The costs of children that are the basis for the proposed new formula reflect the fact that higher-income families pay a greater percentage of their income in tax, and this is one reason why they spend a lower percentage of their income on children. Thus, although the proposed formula continues to be based on taxable income, the impact of income taxation on disposable income has been taken into account indirectly.

Number of children

In the proposed formula the costs of children will be expressed for one child, two children and three or more children, rather than up to five children as it is at present. This simplification is possible because after taking account of the impact of FTB A, the Taskforce found that family spending on four or more children is little different from that on three children. FTB A is payable on a per child basis, and does not take account of the economies of scale that are possible for larger families. This means FTB A is proportionately more generous to large families. While families with higher incomes receive less FTB A, and may not receive any at all, their capacity to spend on each child is constrained as the number of children increases. Consequently, approximately the same proportion of income is spent on four or more children as would be spent on three.

An increased self-support amount

The Taskforce proposes that the current self-support amount, which is currently set at 110 per cent of Parenting Payment (Single) ($13 462 in 2005), be increased to one-third of MTAWE. In the 2005–06 financial year this is projected to be $16 883. This increase is justifiable because the Taskforce research shows that, after taking account of the numbers of children in the household, resident parents have significantly higher equivalised disposable incomes (that is, taking into account the size and composition of the household) as a result of government benefits than non-resident parents who are on incomes below the proposed self-support threshold. The self-support component should be the same for both parents.

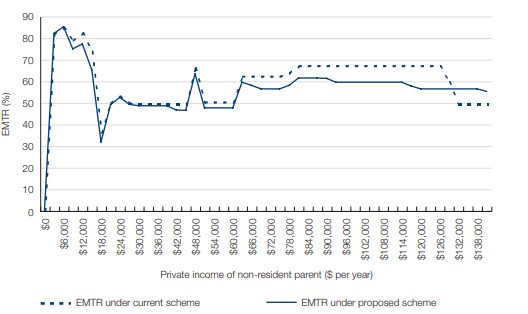

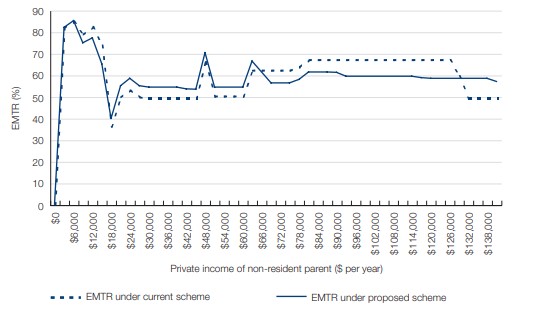

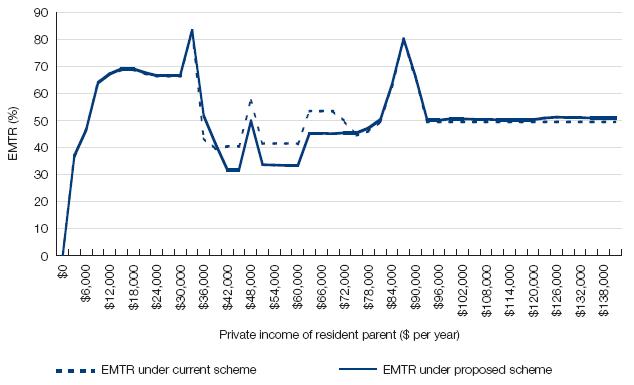

The increased self-support component will improve workforce incentives for both parents. Parents on Newstart will be able to take on casual or part-time jobs to supplement their benefit, without it affecting child support until their earnings reach a level close to where entitlement to Newstart cuts out. Parents on other income support payments will also be able to keep some of their casual or part-time earnings without this affecting child support.

Second families

Children from first and second families ought to be treated as equally as possible. The Taskforce proposes that this should be achieved by taking the amount that the non-resident parent would pay for the new dependent child if he or she were paying child support based upon his or her income alone, and then deducting this amount from his or her available financial resources (together with the self-support amount) in working out his or her capacity to pay child support for the child or children in the first family. This method should replace the current approach of increasing the non-resident parent’s self-support component to 220 per cent of the partnered pension rate plus an additional amount depending on the age of the child or children in the new family.

While some parents with second families may receive a reduced allowance for the new child or children on the basis of this principle compared to the present provisions, the effect of this recommendation needs to be considered together with the impact of all the other recommendations, including a greatly increased self-support amount, fairer recognition of the costs incurred in contact, recognition that the same percentages of before-tax income should not be applied across the income range, and other changes to the way in which child support obligations are calculated. The availability of FTB to the second family should also be taken into account.

Child support children in different families

Where a non-resident parent is required to pay child support to children in two or more different households (having two or more child support cases), his or her contribution to the costs of these children should be calculated using his or her income only. The percentages applicable to the total number of children should be used. The resulting cost should be divided evenly amongst the child support children on a per capita basis. This is consistent with the principle recommended above in relation to second families.

Taking account of regular contact and shared care

Thresholds for recognition in the formula

The current formula does not take adequate account of the costs of contact. A parent has the same child support liability whether he or she has no contact with the children or has the children to stay overnight for 29 per cent of nights per year. The Scheme therefore does not take proper account of the costs incurred when children are staying with the non-resident parent.

In order to recognise that non-resident parents who have regular contact with their children incur significant costs in providing that contact, and relieve the other parent of expenditure on food and entertainment costs at least, the Taskforce considers that regular face-to-face contact should be recognised in the formula.

If a parent has the care of the children once a week on average, or 14 per cent of nights per year, it is likely that he or she will need accommodation that is appropriate for a child to stay regularly overnight. This and other infrastructure costs do not vary much depending on how much contact the parent has. For this reason, the Taskforce considers that recognition of contact arrangements in the formula should begin when a non-resident parent has at least 14 per cent care. If the parents agree that daytime-only contact, or a combination of days and nights, is the equivalent of the expenditure involved for 14 per cent or more nights per year, then the same reduction in child support will be applicable. Otherwise the matter will need to be determined by the Child Support Registrar on application by a parent.

Where care is being shared between the two parents to the extent that each parent has the children for at least five nights per fortnight or 35 per cent of nights per year, the applicable child support should be based upon a shared care formula, with the higher-income parent making a contribution to the lower-income parent after taking account of the proportion of time the children are in each parent’s care.

Care of the child for between 14 and 34 per cent of nights per year is termed ‘regular contact’ in this Report. When parents have the care of the child between 35 and 65 per cent of nights per year each, this is termed ‘shared care’.

The interface with FTB

Currently, the way in which contact and shared care arrangements affect entitlement to FTB is quite different from the position under the Child Support Scheme. In the Child Support Scheme, the child support obligation is not affected unless a parent has the child staying with him or her for 30 per cent or more nights per year. In contrast, FTB can be split where a non-resident parent has 10 per cent or more of the care. Although the care is normally based upon nights, it may be calculated by reference to hours of care. The FTB split is in direct proportion to the level of care, so that a parent with 20 per cent of the time with the child will be eligible for 20 per cent of both FTB A and B.

The Taskforce proposes that the child support and FTB systems be coordinated, so that rather than having two different systems for taking into account regular contact and shared care, there is a consistent approach.

Minimising conflict over care arrangements for children

One of the most significant problems with the way in which contact arrangements affect child support and FTB eligibility is that concerns about money can get in the way of agreements about parenting arrangements that are best for children. This is particularly the case in relation to FTB, as entitlement to FTB is based on the number of nights above 10 per cent of the nights per year that each parent is caring for the child. Thus arguments about whether the children will stay with the non-resident parent for two nights per weekend or three, or have time with him or her in the middle of the week, may have financial implications. Monetary concerns can motivate a non-resident parent to seek increased contact or make the primary caregiver unwilling to agree to increased contact.

The Taskforce considers, on the basis of strong advice emerging from its consultations, that it is in the best interests of children that agreements about parenting arrangements not be affected by financial concerns. While different financial arrangements need to be made for parents with shared care, the Taskforce considers that the level of conflict over money can be minimised if:

- the recognised costs of contact in the formula do not vary depending on the amount of contact between 14 per cent and 34 per cent of nights per year;

- resident parents are entitled to 100 per cent of the FTB where the care of the child is not being shared; and

- FTB splitting is confined to those who have shared care—that is, where each parent has the children for at least 35 per cent of nights, or five nights per fortnight.

Consequently, recognition of the costs of regular contact should be dealt with through the Child Support Scheme rather than through FTB splitting, and the level of child support payable should be calculated on the assumption that the resident parent has the benefit of all the FTB A where the care is not being shared.

Where the non-resident parent is caring for the child between 14 per cent and 34 per cent of nights per year, child support should be calculated on the basis that he or she is credited with a contribution of 24 per cent of the costs of supporting the child through the provision of that care. This figure has been informed by research on the costs of children in separated families. The research demonstrates that, when children are being cared for in two households, the combined costs are much higher than when the children are being cared for in only one household. While the costs of providing for the children do not diminish much for the resident parent (because so many of those costs are related to infrastructure), the costs are, to a significant extent, duplicated in the other parent’s household. The proposed formula makes an allowance for this in a way that reflects the findings of research on families with a modest but adequate standard of living after separation about the proportions of the increased cost of children in two households that are incurred in each household.

Where the parent is caring for the child for 35 per cent of the year, child support should be calculated on the basis that the non-resident parent is bearing 25 per cent of the costs, rising by 0.5 per cent for every night above this until each parent is sharing 50 per cent of the costs for approximately equal care.

Where there is a parenting plan or a court order specifying that the liable parent should have the care of the children for at least 14 per cent of nights per year, this will be assumed to be occurring. The payee may challenge this if the level of actual contact occurring in the current child support year was significantly less than 14 per cent of nights per year, despite the payee’s willingness to make the children available for that contact.

Recognition of costs of contact for low-income parents

There are a number of non-resident parents who would not be as well off under these proposals as under FTB splitting. These are non-resident parents who would receive a lower reduction under the proposed arrangements for taking account of regular contact in the Child Support Scheme than they gain as a result of FTB splitting.

The research of the Taskforce has demonstrated that a significant effect of not splitting FTB A for non-resident parents would be the loss of entitlements to ancillary benefits that flow from eligibility for FTB A, including Rent Assistance and other valuable benefits. To ensure that these benefits remain for those exercising regular contact, it is proposed that non-resident parents who have contact between 14 and 34 per cent of nights per annum will continue to have access to Rent Assistance, the Health Care Card, and the Medicare Safety Net if the other eligibility criteria for FTB A are met. As a consequence, the people who currently have regular contact and are splitting FTB will continue to access significant benefits of splitting, while having a reduction in their child support liability on account of that regular contact.

It is also proposed that non-resident parents who are in receipt of Newstart be paid the ‘with child’ rate of the Newstart Allowance where they have the care of a child for at least 14 per cent of the nights per year. Currently the award of the ‘with child’ rate of Newstart does not appear to be administered uniformly. The proposal in relation to Newstart would ensure consistency across the country and align Newstart with the recognition of regular contact under the Child Support Scheme. The Government may also wish to consider treating both parents in a shared care arrangement (35 to 65 per cent of nights each) more equally in terms of eligibility for income support. At present, where the parents are sharing the care of the child equally, and both would be eligible for Parenting Payment, only one parent can receive it, and the choice between the parents does not have a rational basis.

The formula in operation

Under the proposed new approach, the basic formula will have up to five steps.

- Ascertain the parents’ ‘adjusted taxable incomes’ (meaning, taxable incomes with adjustments made to take account of negative gearing and other such factors) based upon the most recently available tax assessment or such other information as is available. This step is similar to the current calculation of adjusted taxable income for child support purposes.

- Calculate the Child Support Income of each parent. This is equal to their adjusted taxable incomes less their self-support amount. If either parent has a new biological or adopted child, the self-support amount will be increased by the amount that the parent would have to pay in child support based upon his or her income if the child were living elsewhere.

- Calculate the cost of the child or children using the combined Child Support Income of the two parents and applying the relevant amounts in Table A: Costs of Children, in this report. The resulting cost represents the amount that the parents would be likely to spend on the children from their private incomes if they were living together. The cost of the child can be expressed legislatively as a percentage of the parents’ combined Child Support Income within each of the relevant income bands, with each band of additional income attracting a lower percentage. The amounts and income bands are contained in Table A.

This step is fundamentally different from the existing Scheme because it is the cost of the child that is worked out as a percentage of the parents’ combined income above the self-support amount for each parent, whereas in the existing Scheme the payer’s child support obligation is expressed as a percentage of his or her income above the self-support component.

- Apportion the costs of the child in accordance with the parents’ respective capacities to pay—that is, in proportion to their respective shares of combined Child Support Income.

- Where there is regular contact with the non-resident parent (between 14 per cent and 34 per cent of the year), 24 per cent of the costs of the child will be treated as incurred in the non-resident parent’s household. The non-resident parent’s liability is any balance of their share of the costs of the child, after deduction of the amount they are assumed to be expending by providing contact. For amounts of care equal to or above 35 per cent (that is, shared care), a percentage of the costs of the child, as found in Table B, will be treated as having been incurred by the parent with lesser care. When care is equal or near equal, the share will be 50 per cent of the costs. In all cases of shared care, a parent whose share of the combined Child Support Income is greater than his or her share of care will have a liability to the other parent.

Chapter 16 of the main Report contains detailed information about how this formula translates into child support payments for a variety of cameo families. It also provides information on how the formula translates into averages of a paying parent’s income before and after tax in different scenarios. The examples also provide estimates of the disposable incomes of each parent after paying and receiving child support, taking account of the number of people being supported in each household.

Simplicity for the public

Although the formula will be legislatively more complex than the current formula, it will be no more complex administratively, nor will there be any greater complexity for members of the general public. At the present time, people can use a calculator available on the Child Support Agency website to obtain an estimate of a child support liability if they know the father’s income, the mother’s income, and the number of children. With the addition of the requirement to enter the ages of the children, it will be as simple for a member of the public to obtain an estimate of the new child support liability as at present.

Ensuring parents meet their obligations to their children

Minimum payments

More than 40 per cent of all payers in the Child Support Scheme are paying $260 per year ($5 per week) or less. Only about half of these are on Newstart, Disability Support Pension or other income support. It is likely that the reported taxable incomes of many of the remainder do not reflect their real capacity to pay a reasonable amount towards the support of their children.

The use of taxable income as the basis of child support means that those people who legally or illegally manage to minimise their tax also pay unrealistically low levels of child support.

To give effect to the principle that both parents should contribute at least something towards the costs of supporting their children, the required child support payment should be $20 per week per child for those who were not on income support during the tax year on which the current child support amount is calculated, and who report taxable incomes below the level of maximum Parenting Payment (Single). This fixed payment should not be reduced on account of regular contact because it is designed to ensure that those whose reported taxable income does not reflect their real capacity to pay child support make at least a modest contribution towards their children’s upbringing. Those who were on income support for a period during the relevant tax year but have taxable incomes above the self-support amount on the basis of the tax assessment for the relevant year should be assessed on the basis of the formula.

While a parent is on Newstart or another income support payment with income below the self-support amount, the operation of the formula will be suspended and a minimum rate will apply. The minimum is currently $5 per week. The payment should be increased in line with the increase in the CPI since the minimum payment was first introduced in 1999. The payment should become a minimum for each child support case, so that a payer with a liability to children in more than one household would pay the minimum to each household.

The minimum rate and the fixed payment should be increased annually in line with changes in the CPI and rounded to the nearest 10 cents.

Registrar-initiated changes of assessment

Another strategy for ensuring that parents who have the capacity to pay reasonable levels of child support do so is the greater use of Registrar-initiated changes of assessment.

At present, the Child Support Agency has a range of methods by which it can assess the real capacity to pay of a self-employed person who has structured his or her financial affairs so as to minimise taxable income. It also has methods of estimating the real income of those who fraudulently conceal income derived from cash transactions. However, it normally relies on the payee to initiate a change of assessment process on the basis that the parent has a higher capacity to pay than is reflected in his or her taxable income.

Since 1999, the Agency has had the power to initiate changes of assessment of its own motion. This can be very useful in enabling the Agency to look at categories of child support cases that have shared characteristics and where a closer examination of the payer’s finances is warranted. The Taskforce recommends increased resources for this work.

Enforcement

The Taskforce considers that the proper enforcement of child support obligations in relation to all child support payers is essential for popular acceptance of the Scheme. As has been recognised for many years, self-employed non-resident parents who do not meet their obligations to their children represent a particular challenge for the Agency, both in assessment and enforcement. The Taskforce recommends that any enhancement of the Agency’s enforcement powers should be focussed on increasing its enforcement options in relation to self-employed parents who are defaulting on their obligations.

Helping parents to agree

The role of Family Relationship Centres

The new Family Relationship Centres can play an important role in helping separated parents to understand the Child Support Scheme and discuss issues about child support obligations. Group information sessions should draw attention to the flexibility built into the Scheme, in particular through change of assessment applications. Parents should be encouraged also to discuss issues such as paying for childcare costs and plans for future schooling, especially where a private school education was contemplated before separation.

Planning for Family Relationship Centres should involve close collaboration with the Child Support Agency and Centrelink, both of which may be able to provide an information and advice service on the premises of the Centre on a regular basis, perhaps once per week or fortnight. They may also be able to provide input to group information sessions. Both agencies have particular experience in being able to provide advice and assistance to people in regional and rural areas who do not have ready access to face-to-face services. This experience should be drawn on in working out how Family Relationship Centres can service regional and rural Australia.

Giving parents time to work out arrangements

Currently, the operation of the FTB system is such that parents who seek more than base rate FTB A must apply for child support almost immediately, at a time when little discussion may have occurred between the parents about the parenting arrangements after separation.

To give parents more time to adjust to the separation and to discuss a parenting plan, the Taskforce proposes that there should be a moratorium on the requirement to apply for child support (the Maintenance Action Test - or MAT) for 13 weeks. In that period, FTB should be determined as though the MAT has been satisfied.

Child support agreements

The rules on the making of child support agreements can lead to serious disadvantage to payers, payees or the taxpayer, depending on the circumstances, and need to be revised. Parents need to be given as much flexibility as possible in making their own agreements on child support, but there need to be sufficient safeguards to ensure that agreements that have long-term financial consequences for the parents and children are freely and fairly made, and are not used to increase costs for the Commonwealth.

Parents should be able to make binding financial agreements in relation to child support on the same basis as they can do for property, superannuation and spousal maintenance under the Family Law Act 1975. A binding financial agreement is only valid if the parties to it have independent legal advice. Agreements made other than through a binding financial agreement should be terminable by either party on one month’s notice at any time after the first three years of the agreement.

Where an agreement is made for the payment of less child support than would be required under the formula, FTB should be calculated each year on the basis of the amount of child support that the formula would have required if the agreement had not been made. This will have the effect that no agreement can reduce child support for a parent at the expense of taxpayers.

Lump sum child support

The current rules of the Child Support Scheme make it difficult for parents to make agreements about the payment of some child support in a lump sum, including in the form of property, even when this would be of advantage to both parents in establishing themselves in different households after relationship breakdown.

Certain provisions that inhibit parental agreement about lump sum child support are no longer needed to protect the Government from increased expenditure on FTB. Parents ought to be able to make binding financial agreements concerning lump sum child support. As with other types of child support agreement, FTB ought to be calculated on the basis of the amount of child support that the formula would have required if the agreement had not been made. Default rules for working out the impact of lump sum child support on periodic liabilities should be provided in the legislation, in order to make it easier for parents to reach a binding financial agreement on this issue in appropriate circumstances.

The proposed reforms will also make it easier for courts to make lump sum awards of child support where appropriate.

Scope of legislation

In order to ensure that the powers proposed are available to all parents and not only those who were married to one another, the proposed new provisions concerning binding financial agreements and capitalised child support should be contained in the child support legislation.

Other issues

Capacity to earn

Determinations that a parent’s capacity to earn is higher than his or her actual income are amongst the most contentious of all Child Support Agency decisions. Either parent could, in principle, be caught by this provision, but in practice non-resident parents, mainly fathers, are affected. Fathers have complained that this discretion is used unfairly in such situations as where their earnings have been reduced as a result of poor health experienced after separation and divorce, where they have reduced their working hours to allow for contact with their children, or where they have undertaken study to improve their longer-term financial prospects.

The Taskforce recommends that ‘capacity to earn’ should be given clear legislative definition. Parents should only be deemed to be earning more than they are in fact earning, based on unutilised earning capacity, where, on the balance of probabilities, a major motivation for reduced workforce participation is to affect the level of child support payments.

Step-parents

The grounds for change of assessment should be amended to include the recognition of a parent’s obligation to support step-children if neither of the biological parents is able to support the children.

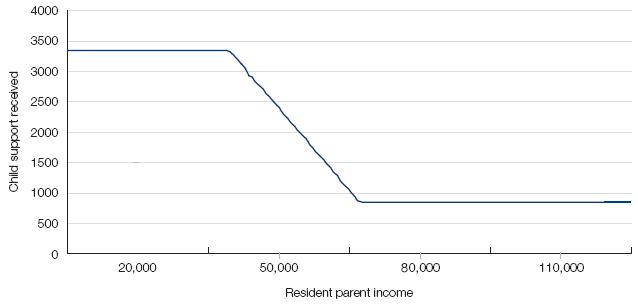

Maintenance Income Test

The Maintenance Income Test (MIT), which dictates how much child support is taken by the Government to recoup some of its expenditure on FTB for the resident parent, is poorly aligned with government policy on support for families. The consequence of the MIT is that many separated parents receive less FTB A than they would if they were living together. There are also other serious anomalies in the current operation of the policy that need to be rectified.

The reform of the MIT needs to be considered by the Government as part of the process of reform when budgetary circumstances allow. In particular, consideration should be given to an increase in the free area before child support payments affect FTB A entitlements.

The MIT should only operate in relation to FTB payable for the child support children and should exclude other children living in the household.

The percentages recommended by the Taskforce in Table A: Costs of Children have been adopted after taking into account the present operation of the MIT.

Revision of the legislation

The child support legislation should be rewritten, as far as possible, in plain English. It is highly complex and difficult to understand, due to an excessive reliance on technical language and complex phraseology. Legislation of this kind must be usable beyond the Agency entrusted with its implementation. Lawyers and other advisers, as well as courts, are significant users of the legislation and it is important to its utility that the legislation should be written without undue complexity.

Other issues related to the Terms of Reference

The recommendations of the Taskforce also deal with a range of other matters of detail concerning the administration of the child support formula or the grounds for change of assessment. The recommendations also address certain legislative matters related to the application of the formula that have emerged from consultations. A number of the recommendations propose changes to promote consistency between the Child Support Scheme and other aspects of government policy in relation to separated parents. A full explanation of the rationale for all the recommendations is contained in the main Report.

The recommendations

The recommendations explain in detail how legislation should be drafted and the Scheme put into operation to give effect to the intentions of the Taskforce. For this reason, many of the recommendations are technical in nature. Recommendation 1, which describes the detail of the proposed new child support formula, is divided into 31 subsections to emphasise that these recommendations constitute a package of interdependent recommendations to be taken together.

Expected outcomes from the reforms

Any changes at all to the Child Support Scheme will necessarily mean changes to the amount of money that some payees receive in child support and that payers must pay.

In some cases, the child support received by payees will increase as a result of these reforms. Recommendations that will have this effect include:

- the provisions for minimum payments;

- recognition of the higher costs of teenagers;

- different treatment of the earnings of resident parents above average weekly earnings; and

- measures to improve compliance.

In other cases, the child support received by payees will decrease as a result of these reforms. Recommendations that will have this effect include:

- recognition in the formula that expenditure on children declines as a percentage of household income as incomes increase;

- the provision for recognition of regular contact in the Child Support Scheme (offset by the limitation of FTB splitting to shared-parenting families); and

- the lower percentages applicable to children aged 0–12.

Where, as a result of these recommendations, child support payments decrease rather than increase, it does not necessarily mean a decline in living standards for children. Children usually have two parents and, where there is regular contact, they live for periods of time in both their parents’ homes. The majority of child support payers, as well as payees, are on modest incomes. Changes in child support obligations will not alter the financial resources available to the children across the two homes. They will only impact on the distribution of those resources between the two homes. Children’s living standards are affected by a range of other factors as well, including government benefits, the resident parent’s workforce participation, and whether the resident parent is living with any other adults in a common household.

As far as possible, the recommendations of the Taskforce are based upon the best evidence available to it about the costs of children, and the most defensible principles for the allocation of those costs between the parents. The Taskforce has recognised many anomalies in the existing Scheme. The correction of those anomalies requires that child support obligations must go up or down. The Taskforce believes that its recommendations can best be assessed by reference not to a comparison between the outcomes of the current and proposed formula, but by reference to the principles and evidence upon which these recommendations are based.

The proposed new formula cannot and will not address all the grievances that people have about the Child Support Scheme. Sometimes grievances about child support reflect concerns about other aspects of family law such as resentment about the difficulties in enforcing contact orders, or disagreement with the ‘no-fault’ basis of Australian divorce law. The Child Support Scheme cannot address these issues—although its design should minimise unnecessary conflict and should be responsive to the strong emotions at play when separated parents are required to work together to provide continuing support for their children.

In the long term, children will benefit most if the proposed formula is seen to be fairer and more explicable than the existing Scheme, if voluntary compliance is increased, and if disincentives to workforce participation for both parents are reduced. It is with children’s interests as the paramount consideration that these recommendations for reform of the Scheme are made to the Government.

Recommendations

Terms used in these recommendations

Child Support Income – a parent’s adjusted taxable income less their self-support amount

FTB – Family Tax Benefit

MTAWE – male total average weekly earnings, as reported by the Australian Bureau of Statistics

Non-resident parent – the parent who cares for the child for less time than the other parent

Payee – the person entitled to receive child support payments towards the cost of children in their care

Payer – the parent who is liable to make a child support payment towards the cost of their child

Regular contact – care of a child by a non-resident parent of 14 per cent or more, but less than 35 per cent of the time

Resident parent – the parent who cares for the child for more time than the other parent

Shared care – care of a child by each parent for at least 35 per cent of the time

Step-child – a child who is neither the biological nor the adoptive child of a person, where the person is either married to, or living in a de facto relationship with, the child’s resident parent

Recommendation 1

The existing formula for the assessment of child support should be replaced by a new formula based upon the principle of shared parental responsibility for the costs of children. The new basic formula should involve first working out the costs of children by reference to the combined incomes of the parents, and then distributing those costs in accordance with the parents’ respective capacities to meet those costs, taking into account their share of the care of the children.

The measurement of income

1.1 For the purposes of the formula, the current definition of adjusted taxable income should be broadened to include certain non-taxable payments such as certain forms of income support, currently exempt.

1.2 The definitions of income for child support and Family Tax Benefit should be consistent and the components should be the same.

1.3 Each parent should have a self-support amount set at the level equivalent to one-third of male total average weekly earnings (MTAWE). Their adjusted taxable income less the self-support amount should be their income for child support purposes (the ‘Child Support Income’). Their Child Support Income should be zero if their adjusted taxable income does not exceed the self-support amount.

The costs of children

1.4 The costs of children for the purposes of calculating child support should reflect the following:

- Expenditure on children rises with age.

- As income rises, expenditure on children rises in absolute terms, but declines in percentage terms.

1.5 The costs of children shall be expressed in a Costs of Children Table based upon the parents’ combined Child Support Income in two age bands, 0–12 and 13–17, and in combination between the age bands for up to three children. (See Table A: Costs of children.)

1.6 Where there are more than three child support children, the cost of the children shall be the cost of three children, and where the children are in both age brackets, the cost of children is based upon the ages of the three eldest children.

1.7 Where there is more than one child support child, and the arrangements concerning regular contact or shared care differ between the children, the cost of each individual child is the cost of the total number of children divided by the total number of such children.

1.8 Combined parental Child Support Income for the purpose of assessing the costs of children shall not exceed 2.5 times MTAWE.

Determining a parent’s contribution to the costs of children

1.9 The parents of the child should contribute to the relevant cost of the child (or children) in proportions equal to each parent’s proportion of the combined Child Support Income.

Regular contact and shared care

1.10 Regular face-to-face contact or shared care by a parent should result in the parent providing the contact or care being taken to satisfy some part of their obligation to support the child.

1.11 If a non-resident parent has a child in his or her care overnight for 14 per cent or more of the nights per year and less than 35 per cent of the nights per year, he or she should be taken to be incurring 24 per cent of the child’s total cost through that regular contact, and his or her child support liability should be reduced accordingly; but this should not result in any child support being paid by the resident parent to the non-resident parent.

1.12 Where the care provided by one parent is equivalent to 35 per cent or more, the parent with 35 per cent of the care of the child will be taken to be incurring 25 per cent of the cost, rising to equal incurring of costs when the care of the child is shared equally. The way in which the cost incurred by the parent with the fewer number of nights of care per year is calculated is set out in Table B: Shared care.

1.13 A parent may also be treated as having regular contact or shared care if either the Child Support Registrar is satisfied, after consultation with the other parent, or the parents agree, that the parent bears a level of expenditure for the child through daytime contact or a combination of daytime and overnight contact that is equivalent to the cost of the child allowed in the formula for regular contact or shared care.

1.14 FTB A and B should no longer be split where the non-resident parent is providing care for the child for less than 35 per cent of the nights per year. Where each parent has the child in their care for 35 per cent of the time or more, FTB should be split in accordance with the same methodology as in Table B.

1.15 Non-resident parents who have care of a child between 14 and 34 per cent of nights per year should continue to have access to Rent Assistance, the Health Care Card, and the Medicare Safety Net if they meet the other eligibility criteria for FTB A at the required rate. They should also be paid the ‘with child’ rate for the relevant income support payments, where they meet the relevant eligibility criteria. The Government should also consider the adequacy of the current level of this rate, in the light of the research on the costs of children conducted by the Taskforce.

1.16 Child support assessment based upon regular contact or shared care should apply if either the terms of a written parenting plan or court order filed with the Child Support Agency specify that the non-resident parent should have the requisite level of care of the child, or the parents agree about the level of contact or shared care occurring.

1.17 The resident parent may object to an assessment based upon the payer having regular contact if the level of actual contact usually occurring in the current child support period is significantly less than 14 per cent care of the child or children, although the payee is willing to make the child or children available for that contact.

1.18 A new assessment may be issued during a child support period if the parents agree that there has been a change in the regular care arrangements amounting to the equivalent of at least one night every fortnight, or there has been a similar degree of change as a result of a court order.

Variations on the basic formula

1.19 All biological and adoptive children of either parent should be treated as equally as possible. Where a parent has a new biological or adopted child living with him or her, other than the child support child or children, the following calculations should take place:

- establish the amount of child support the parent would need to pay for the new dependent child if the child were living elsewhere, using that parent’s Child Support Income alone;

- subtract that amount from the parent’s Child Support Income; and

- calculate and allocate the cost of the child support child or children in accordance with the standard formula, using the parent’s reduced income.

1.20 Where parents each care for one or more of their children, each parent is assessed separately as liable to the other, and the liabilities offset.

1.21 Where a non-resident parent has child support children with more than one partner, his or her child support liability should be calculated on his or her income only and distributed equally between the children.

1.22 Where a resident parent cares for a number of children with different non-resident parents, each of the child support liabilities of the non-resident parents should be calculated separately, without regard to the existence of the other child or children.

1.23 Where a child is cared for by a person who is not the child’s parent, the combined Child Support Income of the parents should be used to assess their liabilities according to their respective capacities. Where a parent has regular contact or shared care of the child, that parent’s liability will be reduced in accordance with the normal operation of the formula.

Minimum payments

1.24 All payers should pay at least a minimum rate equivalent to $5 per week per child support case, indexed to changes in the CPI since 1999. The increased amount should be rounded to the nearest 10 cents.

1.25 A minimum payment should not be required if the payer has regular contact or shared care.

1.26 Payers on the minimum rate should be allowed to remain on that rate for one month after ceasing to be on income support payments or otherwise increasing their income to a level that justifies a child support payment above the minimum rate.

1.27 Parents who are not in receipt of income support payments but report an income lower than the Parenting Payment (Single) maximum annual rate should pay a fixed child support payment of $20 per child per week and this should not be reduced by regular contact.

1.28 The fixed payment of $20 per child per week should not apply if the Child Support Registrar is satisfied that the total financial resources available to support the parent are lower than the Parenting Payment (Single) maximum annual rate. In those cases, the minimum rate per child support case should apply.

1.29 The minimum rate and the fixed payment should be indexed to the CPI from the end of the 2004–05 financial year. The increased payment should be rounded to the nearest 10 cents.

1.30 Where a parent has failed to lodge a tax return for each of the last two financial years preceding the current child support period, and the Child Support Agency has no reliable means of determining the taxable income of the parent, the parent shall be deemed to have an income for child support purposes equivalent to two-thirds of MTAWE. That income may only be changed if the parent files a tax return for the last financial year prior to the child support period to which the deemed income relates, or taxable income information is obtained from a reliable source.

1.31 The Child Support Registrar may report debts arising out of child support obligations based upon a deemed income separately from other accrued debts, but may not reduce a deemed income based on the parent’s failure to meet the obligation.

Assessment and enforcement

Recommendation 2

The Child Support Agency should be given increased resources to investigate the capacity to pay of those who are self employed, or who otherwise reduce their taxable income by organising their financial affairs through companies or trusts, and those who operate partially or wholly by using cash payments to avoid taxation.

Recommendation 3

3.1 The Child Support Agency should be given increased enforcement powers to the extent necessary to be able to improve enforcement in relation to people who are self employed or who otherwise reduce their taxable income by organising their financial affairs through companies or trusts, in particular by:

- broadening the powers available to the CSA to make ongoing deductions from bank accounts to align enforcement measures for non salary and wage earners with those for salary and wage earners;

- aligning CSA powers with Centrelink powers to make additional deductions from Centrelink benefits to cover arrears; and

- providing the power to garnishee other government payments such as Department of Veterans’ Affairs pensions.

3.2 Enforcement powers should not be extended to the cancellation of driving licences for failure to pay child support, as this might reduce parents’ capacity to earn income.

Recommendation 4

Payees should be given all the same powers of application to a court as the Child Support Registrar has for orders in relation to the enforcement of child support, provided either that the payee gives 14 days notice to the Registrar of the application or the notice requirement is otherwise reduced or varied by the court, and that any money recovered under a payee enforcement action be payable to the Commonwealth for distribution to the payee.

Recommendation 5

A court hearing an application for enforcement of child support by a payee parent should have the same powers to obtain information and evidence in relation to either parent as the Child Support Registrar has when enforcing a child support liability.

Recommendation 6

Pending the final outcomes of any application or appeal under Child Support legislation, whether in relation to assessment, registration or collection, the court should have a wide discretion to make orders staying any aspect of assessment, collection or enforcement, including:

- implementing a departure from the formula on an interim basis;

- excluding formula components or administrative changes which might otherwise be available;

- suspending the accrual of debt, and/or late payment penalties, without necessarily having to substitute a different liability for a past period;

- discharging or reducing debt without needing to specify the changes to the assessment to effect this result;

- limiting the range of discretionary enforcement measures available to the Child Support Agency, or staying enforcement altogether; and

- suspending or substituting a different amount of available disbursement to the payee.

Recommendation 7

Section 39(5) of the Child Support (Registration and Collection) Act 1988 should be amended to provide that a payee’s application to opt for agency collection after a period of private collection should not be refused unless it would be unjust to the payer because:

- the payer has been in compliance with his or her child support obligations;

- a failure in compliance has been satisfactorily explained and rectified; or

- there are special circumstances that exist in relation to the liability that make it appropriate to refuse the application.

Overpayments

Recommendation 8

8.1 Where, as the result of administrative error, a payee has been paid an amount not paid by the payer, for example, as the result of the payer’s cheque not being met, or as the result of an incorrect allocation of employer garnishee amounts, the Registrar should not require repayment by the payee.

8.2 Where a payer lodges a late tax return for a child support period, and that return shows a taxable income lower than that used in the assessment, the Child Support Registrar shall vary that payer’s income from the date the return was lodged, but not for the intervening period unless the payer can show good reason for not providing income information at the time the assessment was made. In making a decision whether to vary the payer’s assessment, the Registrar will consider the effect on the payee of having to repay any overpayment thereby created.