Implementation Review of the Family Responsibilities Commission - 2010

Attachments

Final Report - September 2010

- Glossary

- Executive Summary

- Part A – Background to the FRC and its Implementation Review

- Part B – Establishment and implementation of the FRC

- Part C – Post-implementation impacts

- Part D – Contextualising the findings

- A. Terms of Reference

- B. Origin of the FRC

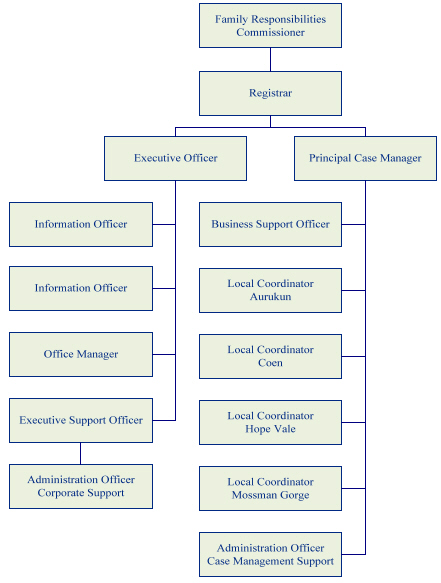

- C. Structure of the FRC

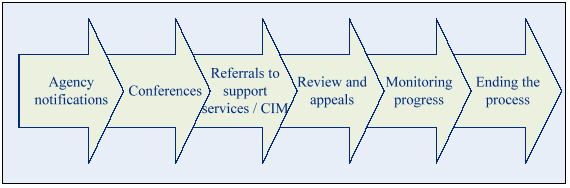

- D. The FRC process

- E. Methodology

- F. Interviews conducted and stakeholders consulted

- G. Supporting program data analysis

- H. Regulation theory and best practice

- I. Cape York Welfare Reform projects and program theory

- Tables and Figures

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

Glossary

| ACMs | Attendance Case Managers

ACMs work to improve the school attendance rate in communities by liaising with parents, students, schools and the broader community to encourage school readiness and attendance. |

| AMP | Alcohol Management Plan

Since 1 January 2003, Alcohol Management Plans have established legalised restrictions to the type and quantity of alcohol that may be brought into a number of Indigenous communities. These restrictions vary from community to community and change over time through negotiations with individual communities. The law applies to all residents and visitors to the community. |

| ATODS | Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drugs Services (Queensland Health)

Provides information, counselling and referral for individuals with concerns related to the use of drugs and alcohol. |

| Bama | Regional name for Indigenous Australians, relating to language groups in north Queensland. |

| CDEP | Community Development and Employment Program

An Australian Government funded initiative for Indigenous job seekers which provides community-managed activities to develop participants' skills and employability in order to assist their move into employment outside CDEP. |

| CIM | Conditional Income Management

CIM involves the FRC sending a notice to the Centrelink Secretary to recommend removing a person’s individual discretion over the spending of a portion of their welfare payments (or direct some of it to a responsible adult in the case of family payments), so that the essential needs of children and families are met. |

| CoAG | Council of Australian Governments

The peak intergovernmental forum in Australia comprising the Prime Minister, State Premiers, Territory Chief Ministers and the President of the Australian Local Government Association. |

| CYI | Cape York Institute for Policy and Leadership

An independent policy and leadership organisation formed in 2004 in partnership with the people of Cape York and Griffith University, with financial support from the Queensland and Australian Governments. CYI provides policy oversight to the FRC through the Family Responsibilities Board. |

| CYP | Cape York Partnerships

An organisation formed in 1999 through an agreement between the Australian and Queensland Governments and regional Indigenous organisations in Cape York Peninsula. CYP is also funded to provide services which form part of the broader welfare reform package, including Attendance Case Managers and Family Income Management. |

| DoHA | Department of Health and Ageing

Federal department responsible for the health and ageing portfolio, focusing on strengthening evidence-based policy advising, improving program management, research, regulation and partnerships with other government agencies, consumers and stakeholders. |

| FaHCSIA | Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs

Federal department responsible for the families, housing, community services and Indigenous Affairs portfolio. The Department aims to improve the lives of Australians by creating opportunities for economic and social participation by individuals, families and communities. |

| FIM | Family Income Management

Funded by FaHCSIA, staffed and managed by Cape York Partnerships (CYP) in partnership with Westpac Bank, the FIM program was operational in each of the communities prior to the Cape York Welfare Reform. It is a voluntary, confidential and free service that is specifically designed to meet the particular needs of Indigenous individuals and families, and provide them with the education, information and ongoing support needed to manage their own money effectively. Family Income Management is different to Conditional Income Management and operates independently of Income Support, however, there are some clients who are both on CIM and on FIM. |

| FRA | Family Responsibilities Agreement

An FRA is a consensual agreement about how the client can work to adopt more socially responsible standards of behaviour and address the issues in their lives which have led to the notification. |

| FRC | Family Responsibilities Commission Statutory body established as a key plank of the Cape York Welfare Reform, to address breaches of obligations imposed on welfare recipients in order to encourage socially responsible behaviour. |

| FRC Act | Family Responsibilities Commission Act 2008(Qld) Legislation establishing and empowering the FRC. |

| LAGs | Local Advisory Groups

Established by the RFDS as part of planning for the transition of Wellbeing Centres to community control, these groups allow for local representatives to have input into planning and service delivery models and is building greater community ownership. |

| LPO | Local Program Office

Representatives of the Tripartite Partners at the local, community level. |

| NOD | Notice of Decision

A compulsory decision that may be made by the FRC if it cannot enter into a consensual agreement with the client. |

| NTA | Notice to Attend

A formal notice issued by the FRC to call individuals to conference. The Local Coordinator currently hand delivers the Notice to Attend Conference to community members. |

| RFDS | Royal Flying Doctor Service

A not-for-profit organisation that delivers primary health care and 24-hour emergency service to Australians in regional and remote areas. RFDS manage the Wellbeing Centres. |

| SETs | Student Education Trusts

SETs enable family members to make regular contributions to their child’s trust which will be used to meet education-related expenses from ‘birth to graduation’. |

| Tripartite Partners | Australian and Queensland Governments and the Cape York Institute for Policy and Leadership

The partners responsible for overseeing and implementing the Cape York Welfare Reform. |

| VIM | Voluntary Income Management

The FRC Act enables the FRC to receive voluntary self-referrals, where a community member asks for the FRC to give Centrelink a notice requiring the person to be subject to income management. |

| WBC | Wellbeing Centres

Wellbeing Centres are funded by the Federal Department of Health and Ageing and managed by the RFDS. The centres provide a range of social support services such as counselling and community activities to address drug and alcohol addiction, mental health issues and other social problems such as family violence or problem gambling. |

Executive summary

- Background

- Implementation Review of the FRC

- The FRC and its functioning

- Findings

- The FRC’s responsive regulation

- The FRC and the Welfare Reform’s Theory of Change

- Summary

Background

The Cape York Welfare Reform is a joint initiative of the Australian and Queensland Governments and the Cape York Institute for Policy and Leadership, and is operating in the remote Queensland communities of Aurukun, Coen, Hope Vale and Mossman Gorge from July 2008-December 2011.

One of the Welfare Reform’s central projects is the Family Responsibilities Commission (FRC). This is a unique regulatory authority, which is time limited, and involves local Indigenous people in decision-making. The FRC aims to support the restoration of socially responsible standards of behaviour and local authority, and to help people resume primary responsibility for their individual and communal wellbeing.

Implementation Review of the FRC

This Report focuses solely on the findings from the Implementation Review of the FRC (Review). This Review has considered the implementation and operation of the FRC in the first 18 months of its 3.5 year term. The objectives of the Review have been to establish:

- whether the FRC is being implemented effectively;

- what might need to be changed or addressed; and

- what initial impacts can be observed.

Terms of Reference that comprise eight questions and a range of sub-questions have guided the conduct of the Review.

A mixed-methods approach was used to collect and analyse information, including:

- visits to the four communities to talk to local people;

- consultation with over 100 stakeholders from the FRC, communities, service providers and government agencies;

- analysis of program and other administrative data; and

- observation of FRC conferences in process.

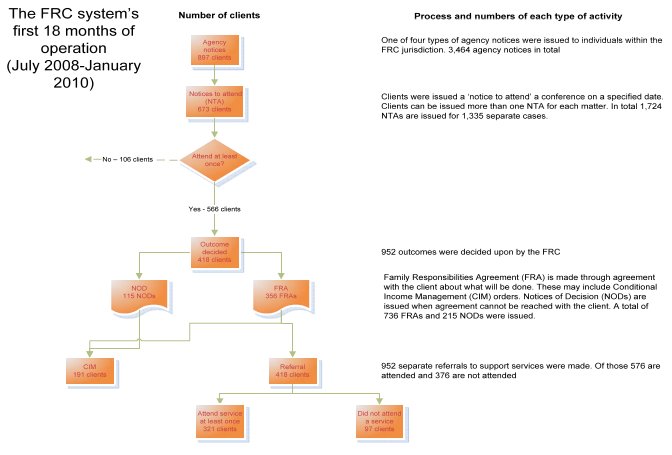

The data collection took place from August 2009 to January 2010 while analysis and validation of data occurred from February to July 2010. The data used to inform this Report are indicative only as it is not possible to have identifiable trends over such a short period of time. They reflect a specific point in time within an evolving context.

Future stages in the evaluation of the Cape York Welfare Reform will consider the whole Reform.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

The FRC and its functioning

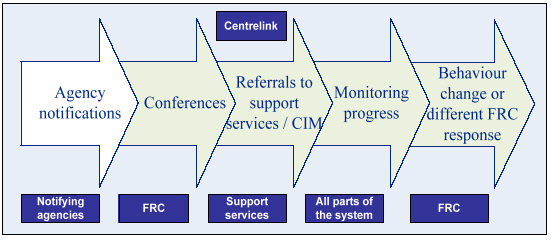

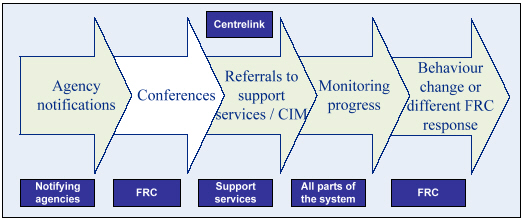

The FRC can be conceptualised as a regulatory body which seeks to change people’s behaviour and the social norms of the reform communities. The FRC forms part of a broader system, together with Queensland Government agencies which notify the Commission of breaches of social obligations, and support services which receive referrals from the FRC. The FRC system can be understood as a network of regulation based on collaboration between local Indigenous leaders, existing authorities and services from education, child protection, housing, income support, police and courts, plus non-government organisations.

The FRC holds conferences with individual community members who are welfare recipients and who have been identified as failing to uphold obligations around caring for children, sending them to school, abiding by the law, or abiding by public housing tenancy agreements. The FRC can refer clients to support services to address issues and barriers to change. Although its primary objective is to provide assistance, the FRC also has the authority to recommend that Centrelink manage a portion of an individual’s welfare payments.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

Findings

The Review has made the following findings. A full list of recommendations is set out in chapter 13.

Implementation and objectives

- The FRC has been successfully established as an innovative new body in accordance with the requirements of the design and legislation.

- The FRC’s jurisdiction is targeted appropriately and it is engaging community members in a very complex environment.

- The process of establishing the FRC system has been more difficult than anticipated, but this is not unusual for changes in which collaboration across organisations at all levels is required, and issues are being worked through

- The FRC is progressing towards its objectives, and there are opportunities to further enhance its influence in the communities.

Initial impacts

- The FRC appears to be contributing to restoring Indigenous authority by supporting local and emerging leaders in Local Commissioner roles to make decisions, model positive behaviour and express their authority outside of the FRC.

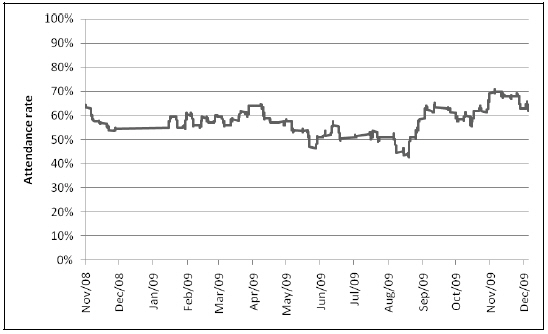

- With average attendance rates of around 60-70 percent at conferences, which compares favourably with other conditional welfare initiatives, and the majority of clients reaching agreements with the FRC about what action they should take to improve their lives, there are signs of individuals responding to the drivers and incentives created by the FRC.

- There is growing awareness in the communities that the FRC is operational and will hold people accountable for certain behaviour, although this understanding is not yet broad or deep.

- Story telling through face-to-face interviews with FRC clients reveals that some people have experienced an improvement in their lives and the lives of their families, although there are also signs that individual change is fragile, with many people breaching another social obligation after being in the FRC system.

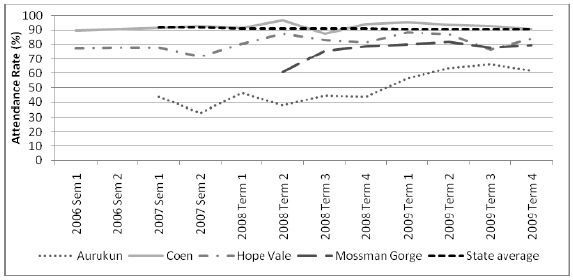

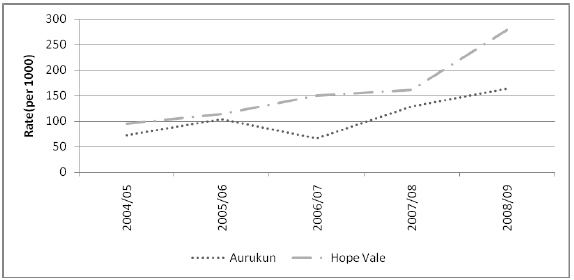

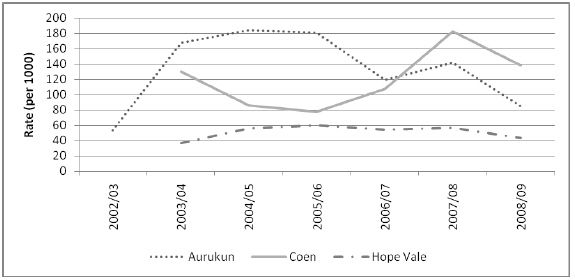

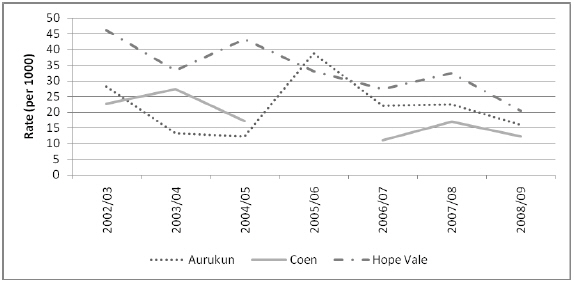

- Indicators of positive community-level change around school attendance, alcohol and violence in two communities (Aurukun and Mossman Gorge) may be associated with the FRC and other initiatives, and underpin a higher level of acceptance of the FRC in these communities.

Focus of improvements for remainder of term

The key issues which require further attention are as follows.

- Development of the FRC system should be progressed, focusing on the linkages and cooperation between the Commission, notifying agencies and support services.

- Forward planning for the volume of clients likely to enter the FRC system for the remainder of its term (including repeat clients) and the associated resourcing required, based on experience to date, is needed. It is critical that the FRC is able to respond quickly to identified breaches of social obligations, to facilitate early intervention and to maintain its credibility.

- Ongoing communication with community members about the FRC, to grow broader understanding about the consequences of negative behaviour and the supports for change to align with community values which it provides, should be continued. For individuals to do more than simply comply, and for changes to extend beyond individual clients to other community members, there needs to be broader understanding of how the FRC insists on and assists with change, and why. Working with sub-groups in the community where acceptance of the FRC is strongest, including former clients, to support them to be influencers within their family group or community will aid realisation of FRC goals and assist in raising awareness.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

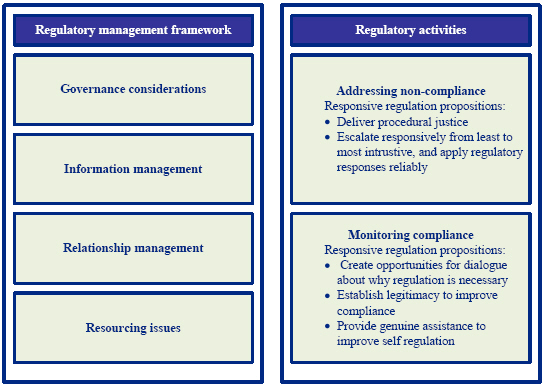

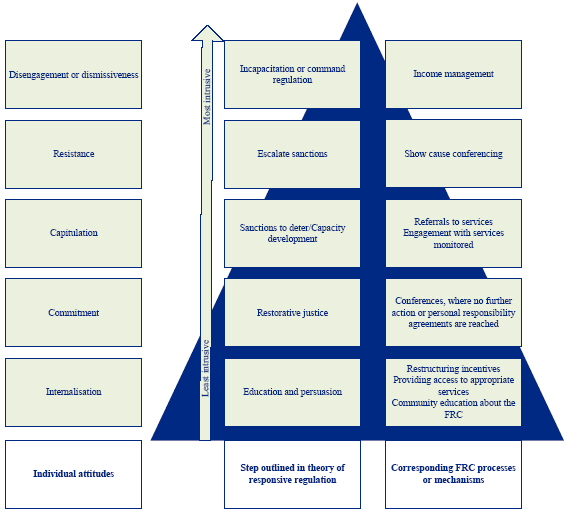

The FRC’s responsive regulation

The Review considered the FRC as a regulatory body according to selected criteria within the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) Administering Regulation Better Practice Guide. Responsive regulation theory, which proposes that the best way to promote self-regulation is to start with the least intrusive strategies and escalate responsively, was also used as a tool to consider the implementation and operation of the FRC system.

The Review has found that the FRC structure and processes largely agree with the principles of good practice and responsive regulation. These principles include:

- the management of risk, information and relationships;

- resourcing and governance; and

- monitoring and enforcing compliance.

Areas where work is required by the FRC system to give effect to these criteria include:

- managing information to monitor client progress;

- regular, formal dialogue with the regulated parties (community members);

- monitoring workload and managing demand; and

- improving the timeliness of responses.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

The FRC and the Welfare Reform’s Theory of Change

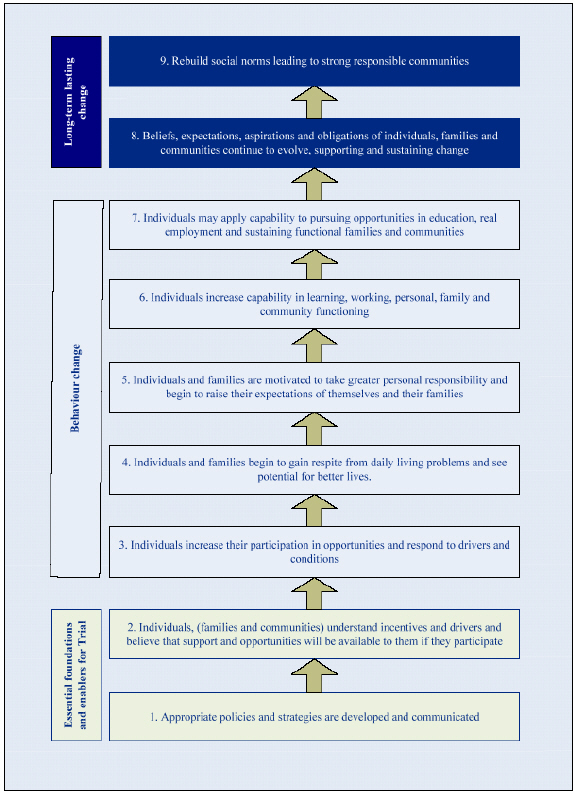

The long-term aims of the Cape York Welfare Reform are complex and ambitious. These involve changes to social behaviours, beliefs and attitudes that are often subtle and difficult to measure and understand. The complexity and interconnectedness of the issues and reforms means that attribution of change to any one activity is not easy.

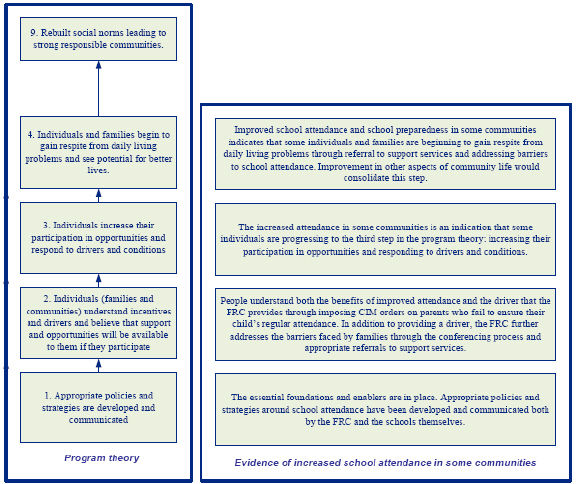

The Welfare Reform’s program theory describes a hierarchy of changes or outcomes that are expected for individuals and families over time through the combination of Welfare Reform projects, including the FRC. The Review’s findings, when analysed with reference to the program theory, indicate that the FRC has laid its own foundations and enablers for both individual and community-level change.

Examples of individual behaviour change through the FRC show that change is gradual and unpredictable, affected by the readiness, understanding, motivation and skills of an individual. Change is not instantaneous and support must be maintained, as while some people might change after one episode of interaction, many people require further support. The FRC conference environment and service referral approach reflects good practice for supporting personal change in this way.

As the FRC begins to reach a critical mass of individuals in each community, and helps to address environmental or common barriers to change, it is expected to contribute to community-level change. The emerging trends of increasing school attendance and decreasing violence in two communities may be the result of a combination of efforts by the FRC and other government and community initiatives. Progress is not even across the communities, and individual behaviour changes can be fragile. This is to be expected considering the complexity of the changes being implemented and the strong support individuals require as they move to align their behaviour with community values.

The data generated by consultation with community members may yield more insights as time passes and further analysis is undertaken. It will be important to analyse trend data and conduct consultations with community members and other stakeholders again in coming years in order to build a longitudinal picture of change.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

Summary

The FRC is a major project within the Welfare Reform, and has a unique and innovative charter. Despite numerous challenges and the complexity of operating within a remote environment, the FRC has been implemented as intended in all four communities. Its structures and processes conform to good practice principles, and during its first 18 months of operations, the FRC has established its own foundations and enablers which contribute to supporting individuals in behaving in ways consistent with community values and expectations of acceptable behaviour. Although many challenges remain, the FRC is already addressing a number of these as it continues to strengthen its role within the participating communities.

Part A – Background to the FRC and its Implementation Review

Summary

The Cape York Welfare Reform is a joint initiative of the Australian and Queensland Governments and the Cape York Institute for Policy and Leadership, and operates in the remote Queensland communities of Aurukun, Coen, Hope Vale and Mossman Gorge.

One of the key projects of the Welfare Reform is the Family Responsibilities Commission (FRC). This is a new regulatory authority that is unique in Australia, time-limited, and involves local Indigenous people in decision-making. Along with other Welfare Reform projects, it aims to support the restoration of socially responsible standards of behaviour and local authority, and to help people resume primary responsibility for the wellbeing of their community.

The FRC conferences with individual community members, who are welfare recipients and have been identified as failing to uphold social norms and related obligations around caring for children, sending them to school, abiding by the law, or abiding by public housing tenancy agreements. The FRC can refer clients to support services to address issues and barriers to change. Although its primary objective is to provide assistance, the FRC also has the authority to recommend that Centrelink manage a portion of an individual’s welfare payments.

The FRC was not intended to operate in isolation. It forms part of a broader system, together with Queensland Government agencies which notify the Commission of breaches of social obligations, and support services which receive referrals from the FRC. It can be understood as a system or network of regulation based on collaboration between local Indigenous leaders and a network of authorities and services from education, child protection, housing, income support, police and courts, plus non-government organisations.

The FRC has a fixed life under its own legislation: it is intended to restore positive social norms and local Indigenous authority to a level where communities can self-regulate thereafter.

This Report focuses solely on the Implementation Review of the FRC. Future stages in the evaluation of the Cape York Welfare Reform will consider the whole Reform.

The Review has considered the implementation and operation of the FRC in the first 18 months of its 3.5 year term. The Report highlights the progress made and recommends changes where these could help to improve the effectiveness of the FRC for the remainder of its term. It also documents the initial changes the FRC appears to be contributing to for individuals and communities.

1. Introduction

- 1.1 The Cape York Welfare Reform

- 1.2 The FRC and system

- 1.3 The FRC Implementation Review

- 1.4 Structure of this report

The Cape York Welfare Reform is a joint initiative of the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA), on behalf of the Australian Government, the Department of Communities on behalf of the Queensland Government and the Cape York Institute for Policy and Leadership (CYI). The Welfare Reform is governed by all three parties together (collectively referred to as the Tripartite Partners). FaHCSIA, on behalf of the Tripartite Partners, engaged KPMG in partnership with Courage Partners to undertake an Implementation Review of the Family Responsibilities Commission (FRC) as the first step in the evaluation of the Cape York Welfare Reform.

This Review has considered the implementation and operation of the FRC in the first 18 months of its 3.5-year term. This Report highlights the progress made and recommends changes where these could help to improve the effectiveness of the FRC for the remainder of its term. It also documents what is happening in the communities and considers this in light of what was expected for the Cape York Welfare Reform overall.

1.1 The Cape York Welfare Reform

The Cape York Welfare Reform is being implemented in Aurukun, Coen, Hope Vale and Mossman Gorge (‘the reform communities’) in the Cape York region of far north Queensland from 1 July 2008 to 31 December 2011 with the financial support of the Australian and Queensland Governments and through the policy guidance of the CYI.

Figure 1: Location of the four communities1

The Cape York Welfare Reform consists of a range of projects and initiatives across four Streams: housing, education, economic development and social responsibility. These are outlined in Appendix I.

The Cape York Welfare Reform is intended to be a catalyst for change in the Cape York region where some Indigenous communities are considered to be living within a culture of reduced personal and community responsibility, believed to be a result of ingrained negative social norms and associated with a culture of passive welfare.2

The Cape York Welfare Reform seeks to tackle Indigenous disadvantage in a way which fosters personal responsibility and local leadership, and supports Indigenous people to effect change in their own lives through rebuilding positive social norms. The Cape York Welfare Reform ultimately aims to:

- restore positive social norms;

- re-establish local Indigenous authority;

- support community and individual engagement in the ‘real economy’; and

- move individuals and families from welfare housing to home ownership.

This Report focuses solely on the findings from the Implementation Review of the FRC. It does not consider other projects or the broader Cape York Welfare Reform context. These are the subject of future evaluation activities to be determined by the Tripartite Partners.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

1.2 The FRC and system

The FRC is situated within the social responsibility Stream3 of the Cape York Welfare Reform, but is designed to be a key agent of change within the broader reform agenda. The Commission is a new regulatory authority that is unique in Australia, time-limited, and involving local Indigenous people in decision-making. It aims to support the restoration of socially responsible standards of behaviour and local authority, and to help people resume primary responsibility for the wellbeing of their community. The Commission also seeks to promote the interests, rights and wellbeing of children and other vulnerable persons living in these communities. See Appendix B for a more description of the establishment of the FRC.

The FRC was established by the Family Responsibilities Commission Act 2008 (Qld) – (the FRC Act), and is an independent Queensland Government statutory authority made up of a legally qualified Commissioner (Commissioner Glasgow) and six Indigenous Local Commissioners from each of the reform communities (24 in total). The Local Commissioners and Commissioner Glasgow hold regular conferences in each community on a circuit, and are supported by Registry staff based in Cairns and the communities.

The conferences are conducted with individual community members who are welfare recipients and have been identified as failing to uphold obligations around caring for children, sending them to school, abiding by the law, or abiding by public housing tenancy agreements (social obligations). The relevant Queensland Government agencies identify breaches of these social obligations and notify the FRC, which then checks that the individuals concerned are within its jurisdiction and decides when to call them to a conference.

The FRC is designed to support the building of personal capacity by first trying to influence the individuals’ desire for behaviour change and addressing environmental and other barriers to change, rather than imposing change. The FRC links individuals to relevant support services in their community: these include case managers to help children attend school; money management advisors; and counsellors for drug and alcohol addiction, family violence and mental health issues. The Commissioners try to reach agreement with individuals on actions they will take to assume responsibility and behave positively, through attending support services or through personal actions such as putting children to bed early. Agreements reached during a conference are documented as a Family Responsibilities Agreement (FRA). However, the FRC also has the authority to make decisions and referrals where the client does not agree.

Although the primary objective is to provide assistance, the FRC also has the authority to recommend that Centrelink manage a portion of an individual’s welfare payments (Conditional Income Management, or CIM). The FRC can use CIM both as a means to ensure financial stability in the home and as an incentive for the individual to engage with support services and observe community obligations.

The FRC was not designed to operate in isolation and is to some extent reliant on the support services and agencies to effect change. Thus the FRC Act establishes a broader system that includes other Queensland Government agencies and community-based support services. Relevant Queensland Government agencies are required to notify the FRC if any of the following events occur:

- a child has three absences in a school term without reasonable excuse or a child is not enrolled in school without a lawful excuse;

- a person is the subject of a Child Safety concern or notification report;

- a Magistrates Court convicts the person of an offence; or

- there is a breach of a public housing tenancy agreement.

The agencies’ role within the system is therefore one of identifying the individuals in each community who may require FRC consideration. At the other end of the FRC process, the system also includes the support services to which the FRC refers clients for help in changing their behaviour and the environment around them. These services also assist the Commission to monitor whether FRC clients are doing what they agreed to in their FRC conference, and are legislatively required to report to the FRC on progress.

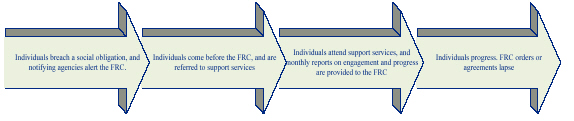

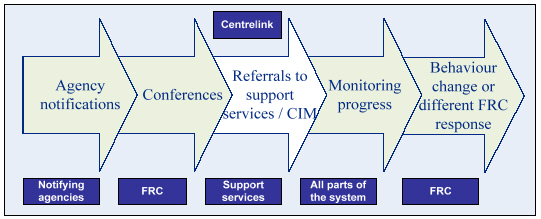

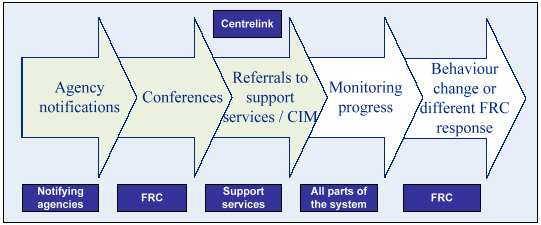

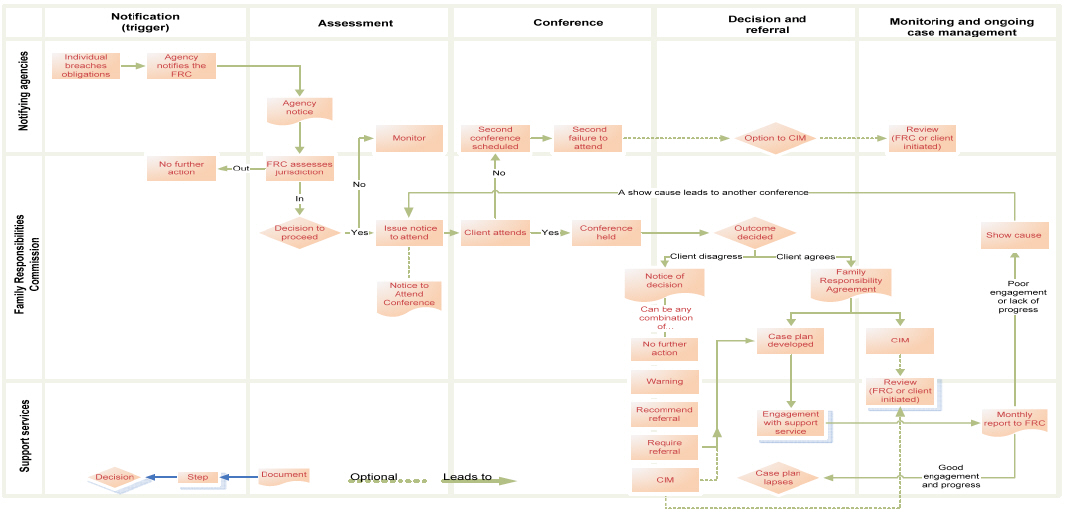

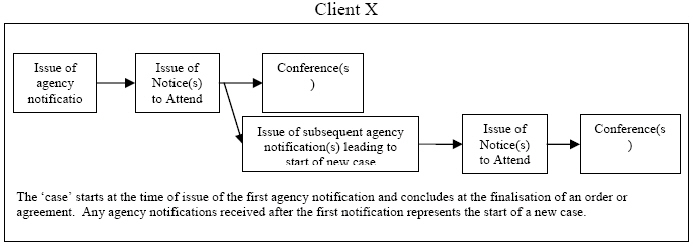

The FRC process involving both the FRC and other parts of the system can take one of two forms. Where an individual changes their behaviour after interaction with the FRC system, the process is generally linear, as illustrated by the following diagram.

Figure 2: FRC process where individual changes their behaviour as a result of FRC interaction

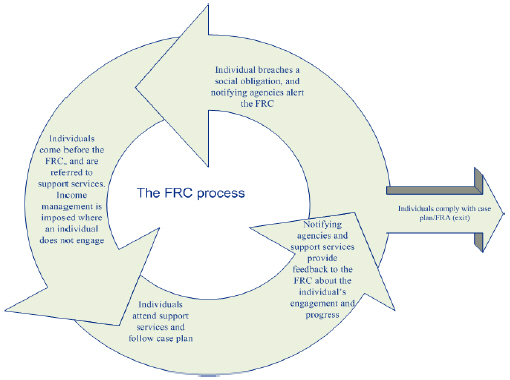

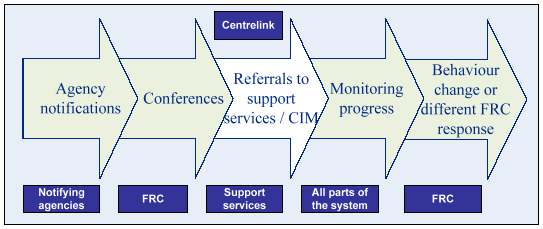

Where individuals do not change their behaviour, either by failing to engage with the FRC and/or support services, or by breaching a social obligation again, they will be called back before the FRC or re-notified to the FRC.

Figure 3: FRC process where individual does not change behaviour

The FRC system can be viewed as a new form of joined-up regulation. This is based on coordination between local Indigenous leaders and a network of authorities and services from education, child protection, housing, income support, police and courts, plus non-government organisations.

The FRC has a fixed life under its own legislation, ceasing to exist on 1 January 2012. The expectation is that positive behaviour and local Indigenous authority will have been restored to a point where communities can then self-regulate in line with the re-established social norms thereafter.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

1.3 The FRC Implementation Review

An Evaluation Framework for the Cape York Welfare Reform (designed by Courage Partners in 2008) recommended that an implementation review of the FRC be undertaken as the first step of the evaluation, in order to understand the successes and challenges of the FRC in implementing its charter, and apply learnings from the review to the FRC throughout the remainder of the Welfare Reform period.

This FRC Implementation Review is therefore only the first stage within the broader evaluation of the Cape York Welfare Reform. The subsequent stages are: a progress review of the whole Reform; and an outcome evaluation of the Reform.

1.3.1 Objectives of the Implementation Review

The FRC Implementation Review commenced in August 2009, with information and data collection ceasing in January 2010. Analysis and validation of data occurred from February to July 2010.

Its objectives have been to establish:

- whether the FRC was being implemented effectively and in such a way that it is likely to achieve its stated objectives;

- what might need to be changed or added to assist the FRC to be effective during the current Welfare Reform period; and

- what initial impacts can be observed in communities and in people’s behaviour, what intended and unintended consequences have occurred, how these impacts and consequences have come about, and to what extent the observed impacts might be attributed to the FRC or to other initiatives.

This Report is explicitly designed to address the Terms of Reference specified for the Implementation Review (see Appendix A). The Review has focused on the FRC as a separate institution and the FRC system in terms of the relationships and processes that link the notifying agencies, Commission and support services. The Review has not looked in-depth at the implementation, operation or quality of the individual notifying agencies or support services.

1.3.2 Methodology

In line with the recommendations of the Evaluation Framework, the Implementation Review used a mixed methods approach to collect and analyse information to answer its Terms of Reference. The approach included:

- a document review of: From Hand Out to Hand Up (the design report for the Cape York Welfare Reform)4, the Family Responsibilities Commission Act 2008 (Qld) and Explanatory Notes for the legislation, FRC Quarterly and Annual Reports, FRC policy and procedure documents, published research on theories of regulation and social norm change and other relevant, publicly available material;

- development of a process map which represents the end-to-end process of the FRC (see Appendix D);

- observation of a two day FRC Training and Cultural Awareness Session held by the Commission with its Cairns and community-based staff in September 2009;

- development of consultation guides for large scale qualitative survey5 interviews, focus groups and individual interviews with FRC clients that were reviewed by an independent advisory group comprising a representative of the Cape York Leadership Academy and Indigenous and non-Indigenous academics;

- consultation with the FRC Commissioner, Registrar, Principal Case Manager and Executive Officer, administrative staff, Local Commissioners and Local Coordinators in each community;

- consultation with representatives of the Tripartite Partners;

- consultation with service providers, notifying agencies, and other relevant community based stakeholders (see Appendix F);

- two rounds of site visits to each community6 in October and November 2009, comprising between five and eight days for each community in total, during which a range of consultation activities occurred including a public meeting, qualitative survey interviews with community members7, focus group discussions, individual interviews with FRC clients and observation of the FRC conferences in operation;

- analysis of de-identified client data from the FRC (i.e. where the privacy of individual clients was protected by removing any identifying information from the data); and

- synthesis, analysis and triangulation (i.e. comparison of data from a range of sources to check validity).

Further detail on the methodology is provided in Appendix E.

1.3.3 Cautionary note for readers

Readers should note that the primary field data informing this Review were collected between August 2009 and January 2010 while the FRC client datasets analysed covers the period July 2008 – December 2009 / January 2010. This Report therefore presents a picture of the implementation and operation of the FRC in the first 18 months of its 3.5 year term (July 2008 – December 2011).

The data used to inform this Report on the Implementation Review are indicative only as it is not possible to have identifiable trends over such a short period of time. They reflect a specific point in time within an evolving context.

In the interests of protecting the privacy of individuals, attribution of comments is not always included.

1.3.4 Theoretical analysis

The Review used two major sources to inform and contextualise its analysis of findings:

- objective, theory-based criteria identified from the literature on regulation (the relevant theory and criteria are described in Appendix H); and

- the program theory for the Cape York Welfare Reform that was proposed in the Evaluation Framework (Appendix I). This program theory outlines the key outcomes that are expected to be seen over time as the Cape York Welfare Reform projects, including the FRC, take effect. Evidence from the Implementation Review was considered to compare the FRC against these expected outcomes.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

1.4 Structure of this report

This report presents the final themes and findings from the Implementation Review of the FRC. It has been structured according to the processes of the Commission and the questions posed by the Terms of Reference.

This report is organised into four Parts, as follows:

| Part A – Background | Terms of Reference questions addressed |

|---|---|

| 1. Introduction | Overview of all |

| Part B – Establishment and implementation | |

| 2. Implementation of the FRC | 1, 3 |

| 3. Identifying and reaching FRC clients | 2, 10 |

| 4. Conferencing processes | 5 |

| 5. Support services | 7 |

| 6. Income management | 6 |

| 7. Monitoring client progress and tailoring responses | 5 |

| Part C – Post-implementation impacts | |

| 8. Re-establishing Indigenous authority and community acceptance of the FRC | 8, 9 |

| 9. What is happening in the communities | 11, 13 |

| 10. Unintended consequences | 12 |

| Part D – Contextualising the findings | |

| 11. The FRC as a regulatory body | All inform the analysis |

| 12. The FRC and the Welfare Reform theory of change | All inform the analysis |

| 13. Recommendations | All |

- Family Responsibilities Commission, 2009, Report to the Family Responsibilities Board and the Minister for Local Government and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Partnerships - Quarterly Report No. 5, July-September 2009. Accessed at

http://www.frcq.org.au/sites/default/files/FRC%20Quarterly%20Report%205.pdf viewed June 2010.

- Cape York Institute for Policy and Leadership, 2007, From Hand Out to Hand Up: Design recommendations, Volumes 1 and 2. Available at:

http://www.cyi.org.au/WEBSITE%20uploads/Welfare%20Reform%20Attachments /Cape%20York%20Welfare%20Reform%20Project%20-%20From%20Hand%20Out%20to%20Hand%20Up%20Volume%202.pdf > viewed February 2010.

- The other three Streams are Education, Economic Opportunity and Housing.

- Cape York Institute, 2007, From Hand Out to Hand Up, opcit.

- This survey used a convenience sample and the findings cannot be generalized to the population overall but contain useful descriptive information. Details of the method are at Appendix E.

- Except Coen where community cultural commitments required one of the two visits planned to be cancelled.

- Many findings in this report are based on a qualitative survey, based on a convenience, non-representative sample. The reported results reflect the perceptions of community members and other stakeholders interviewed. FaHCSIA approved this methodology as it offered a way of gathering a range of peoples’ views via both interview and, where people wished to, via self-completion of the questionnaire. The findings of these interviews cannot be used to make generalizations about the total population, because this sample is not representative.

Part B – Establishment and implementation of the FRC

- 2. Implementation of the FRC

- 3. Identifying and reaching FRC clients

- 4. Conferencing Processes

- 5. Support services

- 6. Income management

- 7. Monitoring client progress and tailoring responses

Summary

This Part looks at the implementation and initial 18 months of operation of the FRC as an institution and within the broader FRC system.

FRC case managers based in each community were a feature discussed during the design, however this was not implemented. The fact that the FRC was operational before some of the necessary support services were available in some communities was also inconsistent with the original design. Improvements to the administrative arrangements should help the FRC achieve its outcomes better, including: amending parts of the legislation to streamline processes, enabling Local Commissioners or a Deputy Commissioner to share the conference load and upgrading physical and technological infrastructure. Barriers and facilitators to implementation include factors internal to the FRC system and environmental factors over which it has limited control. While processes are still being embedded and improved, the FRC and supporting system are implemented and functioning. The FRC has made good progress considering the novelty of the Commission, small staffing complement, difficult operating environment and the sensitive nature of the issues it is dealing with.

The four triggers are appropriate, and largely effectual in identifying community members who will most benefit from interaction with the FRC. Increasing existing efforts to encourage relevant people to attend FRC conferences should be made to ensure that all the people responsible for breaching social obligations are accountable to the community through the FRC. Strengthening the coordination and timeliness of processes between notifying agencies and the FRC would enhance the regulatory network created, and ultimately enable communities to self-regulate.

The average attendance rate for FRC conferences can be understood in different ways, but is between around 60 percent and almost 75 percent. The FRC was able to reach consensual agreement (a Family Responsibilities Agreement) with the majority of clients.

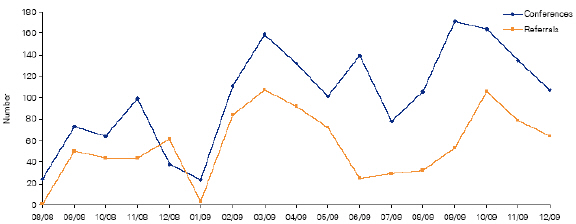

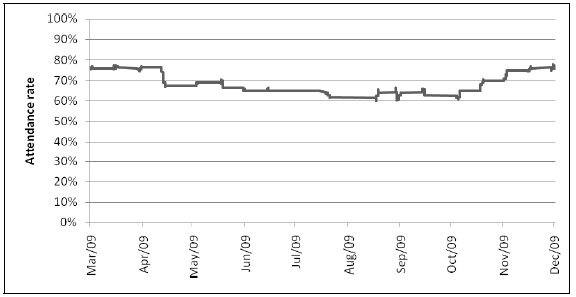

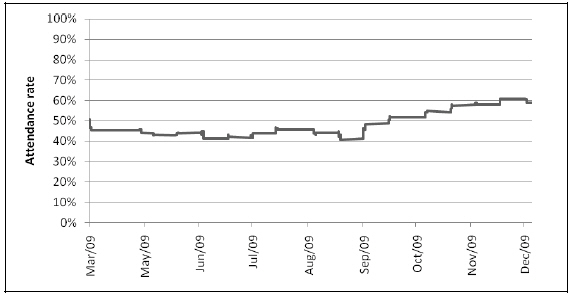

The three key support services are in place in each community, although there are mixed views on appropriateness and accessibility. Establishing the FRC quickly meant limited shared pre-planning and piloting of processes were undertaken and collaborative processes are still being developed. The volume of referrals was higher than expected and continues to be a challenge. Attendance at services is around 60 percent. Mechanisms are needed to improve case management of, and coordination of services to, FRC clients. Improved monitoring of clients’ attendance at support services and progress against case plans is necessary.

Around one-fifth of all FRC clients were or are currently the subject of a Conditional Income Management order. In some cases the FRC use income management as a means to stabilise the family budget and environment to create an environment where other issues can then be addressed. The threat of income management can also be used to motivate people to engage with the FRC and support services, and to change negative behaviours. FRC staff report that many individuals on income management appreciate the structure and stability that it brings, and feel proud when they see they can pay rent, meet bills, afford groceries and have savings. A reduction in discretionary income under the BasicsCard can also be a source of shame, impede people’s ability to travel outside of the community for medical reasons, or to visit family.

The majority (61 percent) of all FRC clients breach another social condition after engaging with the FRC. Personal change is a difficult journey and rarely linear. Greater understanding of why clients breach again, individual changes they are making, and what more is needed will come from improved communication between the FRC and support services, and gathering information from clients on the differences they can see.

2. Implementation of the FRC

- 2.1 Origin and establishment

- 2.2 Implementation against what was planned

- 2.3 Efficacy of administrative arrangements

- 2.4 Facilitators and barriers to implementation

- 2.5 Observations

This chapter reports on the Terms of Reference regarding the implementation of the FRC, with a specific focus on:

- whether there were any departures from what was originally intended to be implemented;

- the Commission’s administrative arrangements and governing legislation; and

- barriers and facilitators to implementation.

This analysis is based on the description of the structure and processes of the FRC in Appendices C and D.

2.1 Origin and establishment

The origins for the FRC are bound up within the origins of the Welfare Reform, summarised below, based on the information provided by the Tripartite Partners.

Under the leadership of Noel Pearson, Cape York Institute (CYI) developed an holistic framework for social and economic reform – the Cape York Agenda – which aims to ensure that “Cape York people have the capabilities to choose the life they have reason to value”. This framework evolved from critical reflection on policy, community consultation and research by Cape York leaders and organisations, and work previously undertaken to develop a regional strategy to address substance abuse. Central to the ideas reflected in the Agenda was the concept of restoring personal responsibility and positive social norms in Indigenous communities through changing the incentives and drivers associated with welfare. This included establishing an FRC-type body. In mid-2005, community leaders from Aurukun, Coen, Hope Vale and Mossman Gorge signed statements of agreement to work with CYI on welfare reform.

The Cape York Welfare Reform Project started in earnest in June 2006 when the Australian Government committed $3 million to the project and the Queensland Government agreed to provide in-kind support. As part of the design phase, the CYI undertook a 12-month community engagement process. A Community Engagement team, made up of two staff based in the communities, engaged leaders and community members in a dialogue around social norms and welfare payment reform. This aimed to ensure community involvement in the project’s design.8 In parallel with the community engagement process, CYI Cairns-based staff continued research and policy design work.

The design phase was governed by a Cape York Welfare Reform Steering Committee which reviewed the key proposals being developed by the CYI concurrently with feedback from the community engagement. This Committee included senior representatives from the Australian and Queensland Governments, CYI and each of the mayors and community leaders of the four communities.9 In late 2007, the four communities each gave their final agreement to participate in the Welfare Reform.10

The results of the community consultation efforts and the policy development were reported to governments in May 2007 through the first volume of From Hand Out To Hand Up. The second volume was released in November 2007.11 Together, the reports proposed a ‘welfare reform trial’ to restore positive social norms and local Indigenous authority, and change behaviours in response to chronic levels of welfare dependency, social dysfunction and economic exclusion. The design report contained recommendations for comprehensive reforms to incentives and services in the Cape York Welfare Reform communities. Among these recommendations were that:

- four obligations be attached to welfare payments (relating to school attendance, child safety, criminal offences and public housing tenancy)12; and

- a new State statutory authority, the FRC, be established by the Queensland Government and empowered to determine whether a breach of the obligations has occurred and take appropriate action.13

While the design drew on research and experience from overseas, and the FRC has elements in line with progressive justice approaches in Australia (such as Drug Courts, Koori Courts and circle sentencing), there were no other working models in Australia to build upon.

After further consultation undertaken by the Queensland Government with relevant State and Commonwealth agencies, and community leaders through various forums (see Appendix B), the Family Responsibilities Commission Act 2008 (Qld) (FRC Act) was passed with bipartisan support on 13 March 2008, establishing the FRC. The FRC commenced operations on 1 July 2008. A sunset clause in the legislation provides that the Commission will cease when the FRC Act expires on 1 January 2012.

Appendix B provides a more detailed description of the design phase, including funding commitments.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

2.2 Implementation against what was planned

The objectives for, and key components of, the FRC are set out in the FRC Act, and reflect the recommendations outlined in From Hand Out to Hand Up.14 The key components include:

- attaching obligations to welfare payments and requiring agency notifications to be issued where breaches of these obligations are observed;

- establishing a separate State statutory authority supported by the Registry and overseen by an independent Board;

- making options available to the FRC in addressing individuals who have breached welfare conditions, including referrals to support services and compulsory income management; and

- the roles and powers of the Commissioner and Local Commissioners.

The Commission uses the FRC Act to guide its operations, and operates consistently across the four communities. However, there are two elements originally envisaged for the FRC system that were not implemented as planned.

The first relates to case management. Consultations with the FRC and Tripartite Partners indicated that initial ideas plans discussed included four FRC case managers, one located within each of the reform communities, to support FRC clients to comply with any case plans developed during conferences. When Wellbeing Centres were developed separately by the federal Department of Health and Ageing, and then linked as one of the support services for FRC clients, the Tripartite Partners subsequently determined that these Centres were better placed than the FRC to play a case management role. Consequently, FRC community-based case manager positions were not implemented on the basis that the Wellbeing Centres would play this role.

However, the Wellbeing Centres were not functional in each community when the FRC was established, and have not taken on a formalised case management role for FRC clients since this time. As discussed in chapter 5, this has limited the FRC’s ability to connect clients to community support services and monitor their progress against FRC case plans. Instead, the Commission has been reliant on support services to engage FRC clients and provide regular feedback on them to be able to assess their progress, which was not always occurring in a meaningful way.

In 2010, the FRC intends to send its Principal Case Manager and recently appointed Business Support Officer to communities on a monthly basis to perform the functions originally envisaged for community-based case managers. This should assist the FRC to address this issue, but continues to require input from FRC staff based in the communities, including the Local Commissioners and Local Coordinators.

The second element which differed from what was envisaged in the Act relates to the set up of the FRC system. The speed with which the FRC was established as a separate body (detailed in Appendix B) meant that it was in place before key support services were established in some communities, so during the early stages the network was not fully functional. This meant that, initially, referrals and case support could not occur as intended. This has created ongoing problems with managing caseloads, referrals and monitoring of case plans, also discussed further in chapter 5.

Apart from these two elements, the FRC and its associated system were implemented as intended.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

2.3 Efficacy of administrative arrangements

The FRC’s administrative arrangements include its governance, legislative framework, staff and systems. In considering whether administrative arrangements were working effectively, the Review examined the impact of administrative practices on the Commission’s ability to achieve its objectives. However a full business service review, necessary to draw conclusions about the efficiency of the FRC, was outside the scope of the Implementation Review.

2.3.1 Governance and reporting

The Family Responsibilities Board is described further in Appendix C. The members of the Cape York Welfare Reform Project Board also make up the Family Responsibilities Board. This enables issues to do with the FRC or its broader system to be raised with the key decision-makers promptly and directly. The support and priority focus for the FRC by both Boards gave the Commission a profile and say in senior levels of both governments which led agency cooperation at regional and local levels.

The FRC Act requires that the Board meets at least once every three months and each member must be present at each meeting.15 This provision of the FRC Act means the members are not empowered to send a delegate and this has delayed obtaining agreement on some decisions when members have been unavailable. If this continues to be an issue, consideration should be given to amending the legislation to allow for two members of the Board to constitute a quorum and for members to nominate delegates. Full advantage should be taken of opportunities to utilise technology to facilitate participation in Board meetings to ensure that decisions can be made in a timely manner.

Working across two levels of government, with multiple agencies and a third non-government body, provides opportunities but also creates complexities. It can also create frequent reporting requirements for the FRC, which has been required to respond to requests for briefings and information from the individual Tripartite Partners as well as report to the Board quarterly in its first 18 months of operation. This was reported by the FRC to represent a significant resource implication for a relatively small body.

It is recommended that the Board explore ways to minimise the reporting requirement on the FRC such as through restructuring reports to suit multiple purposes, and coordinating information requests between members (see also Recommendation 22).

2.3.2 Legislative framework

While a legislative review was outside the scope of this Implementation Review, a number of changes to the FRC Act for consideration within any legislative review were identified in order to:

- ensure procedures enable Commissioners to streamline their activities (especially as they develop experience in administering the legislation);

- ensure that clients are clear about their responsibilities; and

- reduce the administrative burden on the FRC and support services such as through streamlining reporting and procedural requirements.

Interviews with FRC staff and a review of documentation indicated that the FRC relies heavily on the FRC Act to guide its daily operations. The Act identifies specific requirements related to each process step, including receiving a notification, establishing jurisdiction, notifying clients of their conference and monitoring clients after their conference. While this provides clear guidance on how administrative procedures should be undertaken and helps keep operations in line with the rules and purpose of the FRC, it also creates an administrative burden that cannot be streamlined or adapted since the steps are entrenched in legislation. Consistency and clarity in regulation is a key aspect of procedural fairness, which is a principle of good practice in regulation as discussed in chapter 11. The Act enabled consistent, clear practice to be implemented in the establishment of the FRC. However, halfway through its term, the FRC may maintain consistency and clarity in its processes without embedding these in legislation. The agility and responsiveness of the FRC are limited by the need to adhere closely to the FRC Act.

The FRC Act also imposes a heavy reporting requirement on the FRC, requiring five reports to be published a year (quarterly and annual reports).

The legislation specifies a number of documents to be provided to community members and the form that these are to take. These are difficult for some clients to read and understand. The role of the Local Coordinators is, in part, to explain the FRC paperwork to clients but the required documents can still have a negative impact on clients’ engagement with the FRC and the intended process of change. Clients need a user-friendly form of advice.

The FRC is also considering possible recommendations it may make for legislative amendments to the FRC Act. Key changes being explored include:

- Empowering Local Commissioners to convene a conference without Commissioner Glasgow present in certain circumstances – reflecting the capacity and confidence that has developed amongst some Local Commissioners.

- Removing the requirement for FRC case plans – case plans were proposed in the original FRC design when it was envisaged that a FRC social worker/case manager would be placed in each community. As discussed previously, this role was not implemented. In many instances, the support services to which FRC clients are referred are also required to develop detailed case management plans, outlining the clinical requirements of a client’s treatment. This means a client can have multiple case plans, which is confusing for them and complicates service coordination. In practice, FRC case plans usually repeat the information already contained in Family Responsibilities Agreements and as such removing this requirement should not have a have a negative impact on the FRC’s monitoring of client progress or attempts at case coordination.

Evidence from the Implementation Review supports these proposed amendments.

The current legislative requirement that the Commissioner preside over every conference, combined with the travel required and heavy sittings schedule, is a point of vulnerability for the FRC (as discussed in section 2.3.3 below). Conferences would not be able to be held if the Commissioner was to be unavailable without warning. Equipping and empowering the Local Commissioners to convene some conferences without the Commissioner would be one way to manage this risk. This would depend on the readiness of individual Local Commissioners and the capacity of Local Coordinators to provide legal and practical support. The Review found that the confidence and authority of Local Commissioners has grown since the FRC was established (see section 8.1). Many Local Commissioners would like to do more, and identified that ongoing training would be beneficial. If the Local Commissioners were to conduct conferences without Commissioner Glasgow present, it would be important that they had sufficient training, supervision and support to do so well. Issues around Local Commissioners’ understanding of legal requirements and managing family obligations and influences would also need to be considered and addressed.

Such a move would be in line with the objective of the FRC, which is to assist in rebuilding positive norms in the community and restore Indigenous authority.

The duplication of FRC and support service case plans is one of a number of issues with FRC case plans discussed in section 5.5.3. Removing the legislative requirement for separate FRC case plans would both improve the efficiency of FRC processes, and clarify that the development of case plans is the responsibility of support services with the relevant skills and expertise.

In addition, as discussed previously in section 2.3.1, the FRC Act should be amended to enable members of the Family Responsibilities Board to constitute a smaller quorum and to send delegates.

It is recommended that the following changes to the FRC Act be considered in any legislative review:

- streamlining administrative procedures or enabling flexibility to depart from processes where sensible;

- outlining ‘Plain English’ versions of FRC documents that are to be provided to clients, or allowing the FRC discretion to determine the wording of this paperwork depending on the capacity of the client;

- empowering Local Commissioners to convene a conference without Commissioner Glasgow present in certain circumstances;

- removing the requirement for the FRC to produce case plans for clients; and

- allowing for two members of the Board to constitute a quorum and for members to nominate delegates.

2.3.3 The Commissioner

The FRC Act requires that the Commissioner presides over every conference. There is currently no Deputy Commissioner appointed to the FRC, although another Magistrate did act in the role during Commissioner Glasgow’s annual leave in 2009. The current sitting schedule means that the Commissioner is travelling for four days of the week, almost every week. This provides consistency but is a point of vulnerability for the FRC if the Commissioner was to be unavailable without warning, and it may not be sustainable over a longer period of time.

This could be addressed through appointing one or more Deputy Commissioners and sharing conference load (and associated travel) between the Commissioner and Deputy Commissioners, and allow for succession planning. It may also be partially addressed through up skilling and empowering Local Commissioners to convene conferences without the Commissioner or Deputy Commissioner present, as discussed above. To reduce the travel burden, the FRC is also considering conferencing for a period of four weeks followed by one week’s grace period to consolidate the outcomes of conferences held, prepare for upcoming conferences and better case manage FRC clients.

It is recommended that one or more Deputy Commissioners be appointed to share conference loads and enable FRC succession planning.

2.3.4 The Registry staff

FRC staff reported working consistently long hours in the first year of operation to address a high volume of work associated with a greater-than-anticipated client and conferencing load, reporting requirements and external stakeholder interest. At the time staff consultations occurred (September and October 2009), this was an ongoing issue. Since then, there have been changes to the staffing numbers and some roles within the FRC, and it is understood some of these issues have gradually been resolved.

The Review did not analyse FRC staff-client ratios. However the FRC staff’s reportedly heavy workload echoed the experiences reported by the other parts of the FRC system (both notifying agencies and support services). It is also to be expected during the establishment phase of a new body without any working models to draw upon: processes had to be developed from scratch, the client load was unpredictable, and there was a demand for regular reports due to keen policy and public interest. Some aspects of workload should stabilise or become more predictable as the FRC reaches more community members and processes become embedded. However the demand for regular reports will likely continue due to legislative requirements (discussed in subsection 2.3.2 above) and continuing interest in both the FRC and Cape York Welfare Reform for their full term. Ways to minimise the reporting burden such as through restructuring reports to suit multiple purposes, and coordinating information requests, as recommended previously (subsection 2.3.1) should help to alleviate some demand pressure.

2.3.5 Other administrative aspects

The Review found that the FRC’s physical infrastructure (office space and premises) in the communities needs to be examined and upgraded where necessary to provide safe, private and accessible locations to host conferences and support Local Coordinators. Staff reported that accommodation issues, particularly in Hope Vale, have meant that the FRC was initially operating out of sub-standard facilities.

The FRC also experienced significant issues associated with the capacity of the Information Technology (IT) system. This is in the process of being rectified, but was a significant barrier to efficient operations during the first year of implementation, including in relation to: receiving and interrogating information relevant to establishing jurisdiction, client file management, monitoring client progress and generating reports. An optimal IT system would have some capacity to streamline both the FRC’s own data capture and reporting, as well as the processes for mandated information sharing between other parts of the FRC system.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

2.4 Facilitators and barriers to implementation

The facilitators and barriers to implementation to date have included factors internal to the FRC system and environmental factors over which it has limited control. The influence of these facilitators and barriers is evident in the comments through this report

2.4.1 Internal factors - facilitators

Factors which facilitated the establishment of the FRC system which were within its control are identified below.

Staff recruitment

As a new body concentrating on community engagement with a relatively small staffing complement, selecting people with appropriate competencies for community-facing roles was critical to the successful implementation of the FRC. Stakeholders broadly considered that individuals with the right skills, experience and personal attributes filled most of these positions (the Commissioner, Local Commissioners and Local Coordinators). For the Commissioner, these included:

- experience in working with Indigenous people and understanding of the challenges and disadvantage faced;

- being respectful, egalitarian, authoritative; and

- legal qualifications and familiar with independent office.

For Local Commissioners, these included:

- being respected by the community for pre-existing leadership, representation or behaviour;

- having a good understanding of their community, the ability to be representative of the broader community and provide advice to outsiders;

- understanding the core policy objectives and role modelling positive behaviour and norms in line with these; and

- being discreet, protecting people’s privacy and being seen to protect clients’ privacy.

Other roles in the Registry were also seen as facilitators to successful implementation, including the Registrar’s ability to navigate through and negotiate with other government agencies.

The role of CYI and the Community Justice Groups in being able to identify appropriate individuals is important. Going forward, this factor may be maintained through strategies such as reviewing Position Descriptions in light of experience since the FRC’s establishment, trialling new people in roles, and including incumbents and the CYI in selecting future candidates. An independent selection process is important and further discussed in relation to Indigenous authority in chapter 8.

Resourcing

While the client load and associated referrals were unpredictable, and staff workloads across the FRC system heavy in the first 18 months, funding for the FRC and associated processes and services was sufficient to enable it to be established and operational in a short period of time. Committed funds for the term of the Commission enable budgeting within set parameters and forward planning.

Governance

As noted above in section 2.3.1, the structure and support of the Family Responsibilities Board enabled issues to be addressed directly through senior levels of government and Tripartite Partners cooperation.

Inter-governmental consultation and planning

Consultation within government at senior or regional management levels prior to establishment facilitated implementation through raising awareness and identifying issues / concerns, building buy in and planning some processes with notifying agencies.

2.4.2 External factors – facilitators

The CYI’s understanding of community context and needs helped to galvanise government support for the Cape York Welfare Reform as a whole, and test concepts including the FRC, before implementation. It also generated a broad consultation and engagement with community leaders and members before implementation, aiming to build understanding and support of Welfare Reform and the FRC. The proximity to community which CYI as a local, community-owned non-government organisation has cannot be reproduced by government and is a key factor in facilitating implementation.

2.4.3 Internal factors - barriers

Factors which acted as barriers to the implementation of the FRC system which were within the control of the system (the FRC, notifying agencies or support services) included:

- inadequate forecasting of volume of work including the potential pool of clients, reporting requirements and associated staff workloads for notifying agencies, support services and the FRC;

- the FRC being set up before key support services were in place in some communities – this meant there was no time to establish and test processes between them before the system was operational, and a significant lag in support services’ reports on clients’ progress to the FRC emerged;

- a lack of change management processes adopted to explain, train and support staff in notifying agencies and support services to be able to work with the FRC and with compelled clients; and

- variable or ad hoc awareness or engagement strategies during the implementation of the FRC (after community consultations held as part of the design of the Welfare Reform and initial establishment of the Commission). The desire for and importance of ongoing education and engagement is discussed further in section 8.2.1.

2.4.4 External factors

The key environmental factors which were outside of the control of the FRC system were:

- difficulties in recruiting and retaining appropriate staff to positions within notifying agencies, the FRC and support services;

- community support for or opposition to the FRC, Cape York Welfare Reform or other government policies (including the Alcohol Management Plans which restrict alcohol consumption);

- the lack of another working example of a similar body in Australia to model on or learn from, meaning the FRC had to start from scratch, and use trial and error in implementation;

- the relatively small size of the FRC compared to other Queensland Government agencies made the standard accountability, reporting and procedural requirements for the Queensland Public Service resource-intensive to meet;

- changing national and state policy contexts including concerning income management, Remote Service Delivery and economic development initiatives; and

- the size of the vulnerable populations in the communities confronting multiple, complex problems - the communities have fewer resources than urban or regional communities to draw upon to respond to the multiple changes sought by the Cape York Welfare Reform and other catalysts.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

2.5 Observations

The FRC is an unusual body both in Indigenous communities and Australia, with no other working model to draw from. It has been designed and implemented to work with small, vulnerable communities involved in a suite of social and economic changes (some of which are part of the Welfare Reform, while others are broader in scope), which presents a complex operating context.

As a time-limited initiative , much was expected to be achieved in a short period:

- establishing the FRC as a new institution including: recruiting staff in Cairns and the four communities, developing policies and procedures, securing premises for staff and conferences, setting up IT systems, databases, reporting mechanisms, financial delegations, commencing conferences and monitoring cases;

- constructing a broader FRC system through agency-to-agency and people-to-people links between the Commission and: the government departments notifying it about welfare condition breaches; Centrelink which implements Conditional Income Management; and the support services receiving referrals from the FRC; and

- engaging with community members, identifying relevant individuals for the FRC system to begin influencing and enabling them to change behaviour, to work towards changing social norms over time.

The Review has found these things had been achieved in the first 18 months of the FRC’s operation. While processes are still being embedded and improved, the FRC and supporting system is implemented and functioning. The first step in the program theory for the Cape York Welfare Reform (figure 11, chapter 12) is that appropriate policies and strategies are developed and communicated, setting the essential foundations and enablers of the Welfare Reform. The FRC component of the Reform has reached this step.

The range of facilitators and barriers outlined above illustrate the breadth of factors impacting on the success of implementation. Only some of these were within the control of the FRC or system. The novel nature of the FRC means that many challenges and risks were not able to be anticipated prior to implementation. While the design and conceptual development of the FRC took place over several years, the actual implementation was undertaken in a relatively short timeframe. For these reasons it is particularly important that systematic monitoring and Review is in place and issues responded to promptly and appropriately.

The FRC has made good progress in implementation considering its uniqueness, small staffing complement, difficult operating environment and the sensitive nature of the issues it is dealing with.

- Interview with FaHCSIA Welfare Reform Policy Officer, December 2009; Explanatory Notes, Family Responsibilities Commission Bill 2008 (Qld), pp12-13.

- Cape York Institute, 2007, The origins of the Cape York Welfare Reform trial, opcit.

- Cape York Institute, 2007, From Hand Out to Hand Up, Volumes 1 and 2, opcit.

- Referred to throughout this report as ‘social obligations’.

- Cape York Institute, 2007, From Hand Out to Hand Up, opcit, Volume 2, pp.7-9.

- Cape York Institute, 2007, From Hand Out to Hand Up, opcit.

- Family Responsibilities Commission 2008 (Qld), s.123

3. Identifying and reaching FRC clients

- 3.1 Trigger-based system of selecting clients

- 3.2 Issues of jurisdiction

- 3.3 Connections between the FRC and notifying agencies

This chapter looks at how individuals and families in the reform communities are identified to be brought before the FRC. Since this is done through agency notifications, this chapter also looks at the connectivity between the notifying agencies and the Commission. The identification of clients is the first step in the FRC system’s process.

3.1 Trigger-based system of selecting clients

3.1.1 Rationale for the triggers

The four ‘trigger’ events which bring an individual before the FRC are breaches of the social obligations described in section 1.2. It is important to understand the operational issues associated with running a trigger-based system of selecting clients, as these may influence the success of the FRC, its coverage of clients and its reach across the communities.

The triggers16 were originally proposed in the design of the Cape York Welfare Reform to target particular dysfunctional behaviours that are not in line with the stated values of the four communities. The triggers for the FRC reflect the priority issues which local people felt were a concern and not consistent with their vision for the type of community they wanted to live in.

The original Design viewed disadvantage as being where individuals have inadequate capabilities to exercise meaningful life choices or live the life they value. It argued that disadvantage is one of the causes of dysfunction, such as individual behaviours of passivity and addiction, but also that dysfunction has, in turn, begun to limit capabilities and further drive disadvantage. The Cape York Welfare Reform, including the FRC, is intended to attempt to break this vicious cycle.

The social obligations were selected on the basis of three rationales:

- they are consistent with the values expressed by community members (in the community engagement process of the Design);

- they relate to behaviour which, if allowed to continue, would have a negative impact on child wellbeing; and/or

- the pre-existing legislative and service delivery mechanisms aimed at addressing these dysfunctional behaviours in Cape York are unable to realise the desired outcomes. The social obligations deliberately complement or mirror existing laws – breaching these obligations simply provides a different consequence for the dysfunctional behaviour than under pre-existing mechanisms.

The jurisdiction of the FRC set by the Act means that social obligations apply to all adult recipients of welfare payments who live17 in the communities. The Design did not favour the idea of giving individuals in the communities the option to be subject to the social obligations because it was thought that only community members who were already abiding by the obligations would be likely to opt in, and the most troubled members of the communities would not be reached. Instead, it was considered that, if the FRC was to contribute to building positive social norms, all members of the community would have to be included.18

3.1.2 Appropriateness of the triggers

Administration of the trigger based system is complex and highly resource intensive. It is necessary for the FRC to process some data manually because the information management systems of the various agencies are not necessarily compatible with the FRC’s (see discussion at section 3.3 below). Decisions are at each stage are informed by a combination of information from various agencies including Centrelink and the local knowledge and understanding of the Commissioners, Local Coordinators and the Principal Case Manager.

The Terms of Reference for the Review asked whether the triggers are sensitive enough to bring the most disadvantaged and dysfunctional families to the FRC.

The Review analysed FRC client data and qualitative information collected through stakeholder consultations. It was not possible to measure the disadvantage or dysfunction of all people resident in the communities, but examination of the characteristics of those identified in agency notifications provided some indication of the challenges confronting FRC clients. The data are detailed in Appendix G and key points are highlighted here.

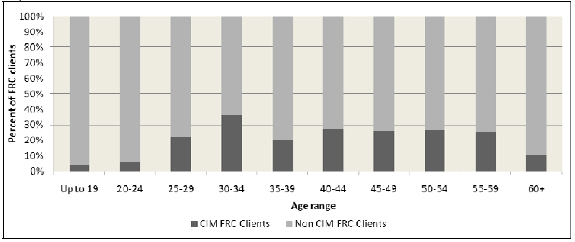

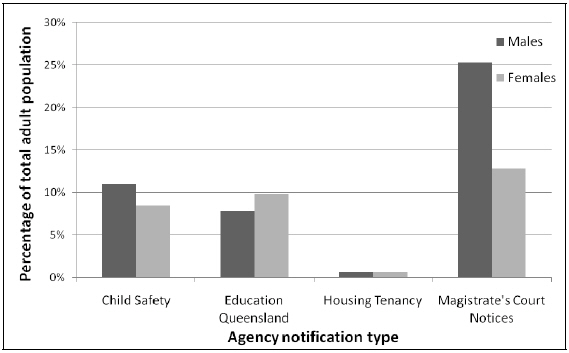

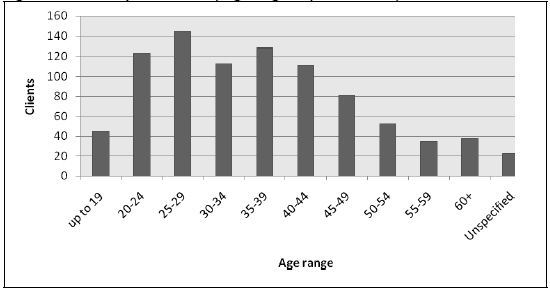

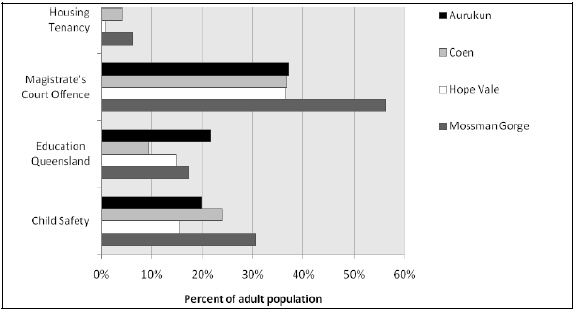

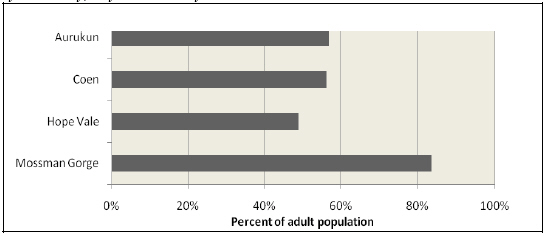

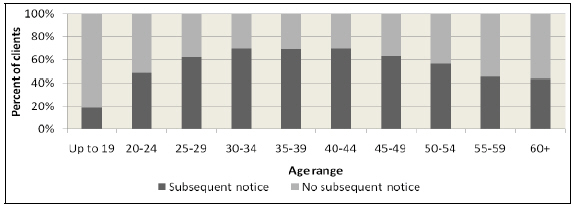

In the first 18 months of the operation of the FRC system, approximately 50-60 percent of the communities’ combined adult population had been identified in an agency notification. In Mossman Gorge over 80 percent of the community’s adult population had been identified in an agency notification in the same period. Magistrate Court notifications were the most frequently issued type, and most agency notifications concerned men aged between 20-39 years. Statistical modelling identified that:

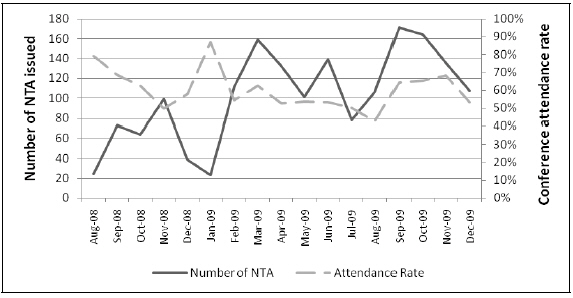

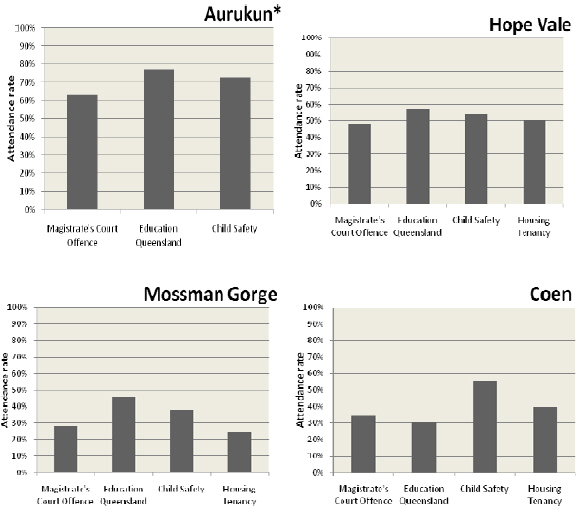

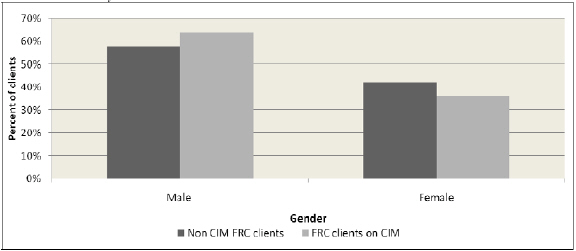

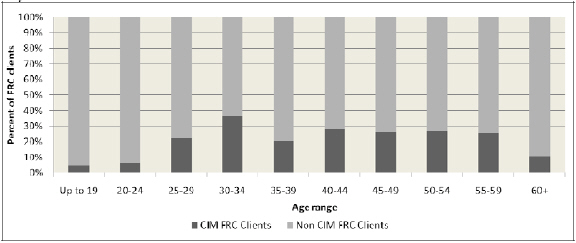

- clients who were identified in a Magistrates Court offence agency notification were more likely to be younger than clients named in other agency notification types, and were more likely to be men. Agency notifications are also more frequent for residents of Hope Vale after taking into account the different populations of each community. and