Evaluation Framework for New Income Management (NIM)

December 2010

This outlines a framework for the evaluation of the NIM model in the NT. The framework is intended to provide a broad structure for the evaluation. It addresses the scope of assessment, high-level research questions, study design, methodologies and proposed data and sources.

Executive summary

In May 2010, a consortium of experts from the Social Policy Research Centre (SPRC), the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) and the Australian National University (ANU) was engaged by the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) to develop an overarching framework for the evaluation of new income management (NIM) to guide evaluation activities over the period 2010-14.

The terms of reference for developing the evaluation framework are that the evaluation activities:

- be completed and reported by December 2014

- provide information on the implementation of the NIM in the Northern Territory by the end of 2011 in order to inform decisions about an expansion of the model beyond the Northern Territory

- result in data being collected that can be used to evaluate short, medium and, where possible, longer-term impacts/outcomes of new income management

- include a set of ethics guidelines and an ethical clearance strategy relevant to this evaluation project.

This document outlines a framework for the evaluation of the NIM model in the NT. The framework is intended to provide a broad structure for the evaluation. It addresses the scope of assessment, high-level research questions, study design, methodologies and proposed data and sources. (See Section 4 for more detail.)

Undertaking the evaluation will require an iterative approach and, as such, it is expected that some elements of this framework (including the program logic, the design of research instruments and detailed questions) will need further development as the project progresses.

The development of the evaluation framework involved extensive consultations with both government and non government sectors. The evaluation framework takes account of:

- the way in which NIM is being implemented, especially that it has been rolled out to the whole of the Northern Territory in a short period of time

- the previous income management policy which has been operating in the Northern Territory since 2007

- the fact that other policies may change at the same time as NIM is being implemented

- practical challenges involved in collecting data in remote areas of the Northern Territory

- particular ethical issues involved in collecting data from vulnerable groups including: children, women, the elderly, Indigenous Australians, and people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.

It takes a multi-method approach (also called triangulation) as it is not appropriate to use an experimental design on a complex social policy such as this. This means collecting different types of primary data (qualitative and quantitative), using secondary administrative and survey data, and collecting information on the same questions from multiple informants (e.g. those being income managed, Centrelink staff, financial counsellors, child protection workers).

As a first step, the framework involves collecting data for an early implementation snapshot, which will also provide benchmarking data for the evaluation. The consortium of researchers who developed this evaluation framework has been commissioned to collect the majority of the early implementation data.

The development of the evaluation framework and collection of the early implementation snapshot data constitutes Phase 1 of the evaluation. The conduct of a comprehensive and independent evaluation of the NIM constitutes Phase 2.

Phase 2 involves evaluating:

- the effectiveness of the program's implementation

- whether the program was delivered as intended to the target population in a fair and equitable manner (including access to necessary services)

- an assessment of the impacts of NIM on individuals, families and communities in the Northern Territory and

- an analysis of value for money (to the extent that this is achievable within the timeframe of this evaluation).

The evaluation is designed to produce the data necessary to evaluate short, medium and, where possible, the longer-term outcomes of NIM. The short term outcomes are foundations and enablers for the measure, and should be evident within the early years of the evaluation project. Behavioural changes/outcomes could occur in the medium term and be evident within the life of this evaluation project. However, some of the longer-term and sustained changes in behaviour are likely to take a number of years to become evident.

All evaluation activities will need to continue to be undertaken in close consultation with both government and non-government stakeholders.

A requirement of the evaluation framework was that it allow the data to be produced to enable reports to be delivered to FaHCSIA by end of each calendar year from 2011-2014, including:

- a substantial progress report addressing implementation issues and early progress in achieving short term outcomes, by the end of 2011

- annual intermediate evaluation reports that synthesise results to date and inform future analysis, by the end of 2012 and 2013 and

- a final outcome evaluation report by the end of 2014.

1. Introduction

Legislation for the model of new income management was passed on 1 July 2010 and was introduced by the Australian Government from 9 August 2010. The model first commenced in the Northern Territory (NT) in urban, regional and remote areas. Over time, and drawing on evidence from implementation experience in the NT, it may progressively be rolled out more broadly across Australia.

The Australian Government Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) has commissioned a consortium of researchers from the Social Policy Research Centre, the Australian Institute of Family Studies and the Australian National University (Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research and the Research School of Economics) to assist in the development of a framework for the evaluation of the new model of income management.

A transparent and objective evaluation process increases the credibility of the assessment of the new measure of income management. The involvement of an external and independent evaluator will provide legitimacy to both the evaluation process and the assessment of the measure.

Ideally, in evaluating social policies data would be collected prior to the implementation of the policy (baseline data). Data collected after the implementation of the policy would then be compared to the baseline data to track changes over time.

However, in the case of NIM, income management has been implemented in 73 discrete communities since 2008 as part of the Northern Territory Emergency Response, which makes collecting ‘pure' baseline data (ie to identify the circumstances and beliefs of people before the implementation of policy) impossible. Even if it were possible to have ‘pure' baseline data, other policies that may also affect people in the Northern Territory who are subject to income management have also been subject to change. Thus, it would not be possible to attribute, confidently, pre- and post-implementation differences in data collected to the NIM measure.

Given that it is not possible to collect ‘pure' baseline data in this context, the evaluation framework includes an early implementation snapshot study. This should provide information to complement administrative baseline data generated prior to implementation of income management policy. Together, these will provide benchmark data for the assessment of NIM.

The implementation snapshot should include collection and analysis of primary data from a wide range of people affected by NIM or involved in administering or implementing the model. This would include people who are income managed, community leaders, Centrelink staff, merchants, money management and financial counselling service providers, and child protection workers.

The evaluation framework is designed to ensure the key evaluation questions will be able to be answered using data collected from multiple sources, using both quantitative and qualitative research methods. This will provide "triangulation" for the key findings of the evaluation.

The terms of reference for developing the evaluation framework are that the evaluation:

- be completed by December 2014

- provide information on the implementation of the NIM in the Northern Territory by the end of 2011 in order to inform decisions about an expansion of the model beyond the Northern Territory

- result in data being collected that can be used to evaluate short, medium and, where possible, longer-term impacts/outcomes of new income management, and

- include a set of ethics guidelines and an ethical clearance strategy relevant to this evaluation project.

This document outlines a framework for the evaluation of the NIM model in the NT and should not be read as a detailed evaluation work plan. The evaluation itself will have to establish the practicality of the approach proposed here, in particular the availability and quality of the various secondary datasets, and the specific issues involved in engaging with individuals, families and communities affected by NIM. The conceptual basis for the program, including the description of the new income management policy and the program logic, is described in detail in Sections 2 and 3. Sections 4-6 outline the consortium's proposed evaluation framework including challenges in evaluating this measure, the study design and methodology and proposed reporting timelines.

Background information to the development of NIM can be found at Appendix A. Appendix B discusses current income management evaluation activities undertaken by FaHCSIA. Appendix C provides FaHCSIA's program logic model for the NIM model. Appendix D shows the hierarchy of outcomes and associated data.

A comprehensive English language literature reviewon evaluation methodologies used to evaluate relevant international programs such as conditional cash transfers and financial counselling programs is at Appendix E. A list of data sources needed to support the evaluation is at Appendix F, while Appendix G describes other funded initiatives in the NT that support vulnerable children and families.

In developing the framework, extensive consultations have been undertaken with staff from the Northern Territory Department of Health and Families, the Western Australian Department of Child Protection, Centrelink, the Department of Finance and Deregulation, Government and Non-Government Think Tank Reference Groups, and the Australian Government Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs.

2. The new model of income management

Income management was first introduced in 2007 as part of the Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER). The initial rollout of income management only affected people who received income support or family assistance payments and who lived in the 73 prescribed communities, their associated outstations and the 10 town camp regions of the Northern Territory.

The new model of income management was introduced on 1 July 2010. The new program differs from the previous model, in particular with regard to the targeting of particular groups of income support recipients. Importantly NIM applies to people who meet criteria independent of their race or ethnicity—this is consistent with the Racial Discrimination Act of 1975 (RDA). Information on earlier initiatives and background to the development of new income management is at Appendix A.

Implementation of new income management commenced on 9 August 2010 in the Barkly region (Zone 1). Implementation in Zone 2 – Alice Springs, Katherine, East Arnhem Land and other outback areas – commenced on 30 August. Implementation in the remaining zones commenced on 20 September (outback areas) and 4 October (Darwin and Palmerston). It is expected that most people will have been transitioned from the old scheme to new income management by 31 December 2010.

2.1 What is income management?

Under income management, a percentage of a person’s welfare payments is set aside for their priority needs and those of their children and families. This helps to ensure that:

- money paid by the government for the benefit of children is directed to the priority needs of children

- women, the elderly and other vulnerable community members are provided with better financial security, and

- the amount of cash in communities is reduced to help counter substance abuse, gambling and other anti-social behaviours that can lead to child abuse and community dysfunction.

Income managed funds cannot be used to purchase excluded goods, including alcohol, home brew kits, home brew concentrates, tobacco products, pornographic material and gambling goods and activities.

Income managed funds must be directed towards agreed priority needs and services such as food, rent and utilities. This process assists families to meet essential household needs and expenses.

2.2 Rates of income managed funds

An individual's income support and family assistance payments are income managed at 50 per cent for the participation/parenting (mainstream), vulnerable and voluntary streams and 70 per cent for the child protection stream. Any lump sums (e.g. Baby Bonus) and advance payments are income managed at 100 per cent. The portion of an individual’s regular fortnightly payments that is not subject to income management (i.e. the discretionary funds) is paid in the usual way.

Income management does not reduce the total amount of payment an individual receives from Centrelink. It only changes the way in which they receive their payments. Individuals can spend their income managed money by using the BasicsCard at approved stores, or by arranging direct payments to organisations such as community stores, landlords, or utility providers.

2.3 Categories or streams of new model of income management

The NIM model is more targeted in its approach than the previous income management measure under the NTER. For the purposes of this framework, NIM has been described using four broad streams or categories:

2.3.1 Participation/parenting (mainstream) stream

- For disengaged youth—people aged 15 to 24 years who have been in receipt of specified welfare payments (Youth Allowance, Newstart Allowance, Special Benefit or Parenting Payment) for more than three of the last six months.

- For long-term welfare recipients—people aged 25 years and above who are on specified welfare payments such as Newstart Allowance and Parenting Payment for more than one year in the last two years.

2.3.2 Child protection stream

- For parents and/or carers referred for income management by a child protection worker. Child protection authorities will refer people for compulsory income management if the child protection worker deems that income management might contribute to improved outcomes for children at risk. This measure will apply at the discretion of a State or Territory child protection worker.

2.3.3. Vulnerable stream

- For vulnerable welfare payments recipients who would benefit from income management in order to meet their social and parental responsibilities, to manage their money responsibly, and to build and maintain reasonable self-care. This stream provides Centrelink Social Workers with an additional tool to help individuals who are vulnerable and/or at risk (e.g. Individuals on Age pension or Disability Support Pension and those subject to financial harassment). It can only be applied following an assessment by a Centrelink Social Worker.

2.3.4 Voluntary stream

- For people on income support who wish to volunteer for income management to assist them to meet their priority needs and to learn how to manage their finances for themselves and/or their family in the long term.

The pathways into the new income management measure are shown in Figure 1, below:

Figure 1. From old to new: an illustration of major pathways for the new income management measure1

Figure 1 represents the pathways for customers to experience the new model of income management.

Previous income management customers under the Northern Territory Emergency response and new customers to income management can transition on to new income management through three compulsory measures or through voluntary income management. Each compulsory measure has specific eligibility factors.

Individuals moving off income management can be out of scope, exempt from income management or otherwise not be subject to income management due to moving to a non-income management area.

2.4 Additional features including incentives for people on income management

The new model of income management has a number of additional features.

- The Matched Savings Payment is an incentive payment to encourage people on income management to develop a savings pattern and increase their capacity to manage their money. If eligible, a person can receive $1 for every $1 they save, up to a maximum of $500. A person can only receive a Matched Savings Payment once. The Matched Savings Payment is paid directly into the person’s income management account.

To receive a Matched Savings payment an individual must:- be income managed (excluding VIM and Cape York income management)

- complete an approved money management course

- maintain a pattern of savings from their discretionary funds for 13 weeks or longer after the commencement of the approved money management course and

- not have previously received a Matched Savings Payment.

- The Voluntary Income Management Incentive Payment is a payment to encourage people who are not income managed but who might benefit from it to volunteer for income management and to continue to participate in it long enough to recognise its benefits. Individuals who voluntarily participate in income management are eligible for an incentive of $250 for every six months they remain on VIM.

- Income management is supported by financial counselling and money management services, totalling $53 million over four years. Income management arrangements introduced under the NTER will operate until 30 June 2011, while people are transitioned to the new model.

2.5 Exemptions

The new model of income management provides pathways to evidence-based exemptions for people under the participation/parenting (mainstream) stream of income management. For people with children, exemptions will be based on a financial vulnerability assessment and demonstrated evidence of responsible parenting activities for their children. These include regular child health checks and immunisations, and participation by the child in age appropriate, social, learning or physical activities.

Individuals referred to the child protection or the vulnerable streams are not eligible for exemption pathways. However, appeal processes are available through Centrelink, the Social Security Appeals Tribunal and the Northern Territory Government. See Section 2.6 below for more detail.

For people without children, exemptions will be based on a demonstrated record of or participation in employment and study.

2.6 Appeal rights

Under the new model of income management people will have access to the full range of review and appeal rights through Centrelink’s Authorised Review Officers and the Social Security Appeals Tribunal. Additionally reviews and appeals processes will be available through the Northern Territory Government specifically for the Child Protection Measure

- As this figure only represents the major pathways for the new income management measure, it may not capture the nuances of individual circumstances.

3. Program logic

Program logic (also referred to as theory of change), has been used to develop and evaluate programs and initiatives since the early 1970s. It improves the quality and focus of evaluation advice to government.

This process is used to ‘surface the implicit theory of action inherent in the proposed intervention in order to delineate what should happen if the theory is correct and to identify short medium and long term indicators of changes which can provide evidence on which to base evaluations' (London et al, 1996).

In order to evaluate NIM it is important to clearly articulate the objectives of the policy and the criteria by which the success or failure of the policy in meeting the objectives set for it are to be evaluated. It is also important for the evaluation methodology to be able to identify any unintended impacts, both positive and negative.

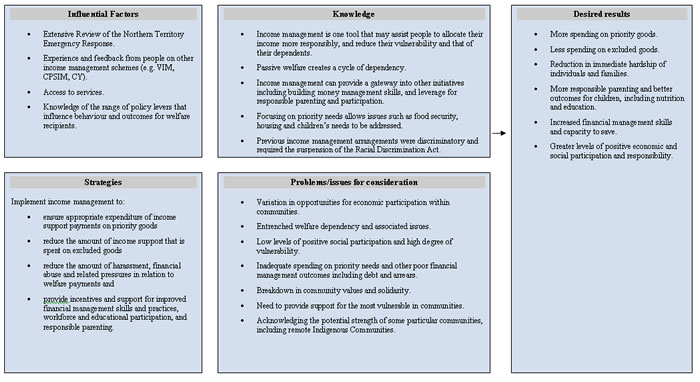

This section outlines the concept map for the NIM model (see Figure 2). A high-level concept map sets out the most important components of the program logic:

- the knowledge base underlying the program

- the strategies to be adopted as part of the program

- the problems to be addressed

- the needs and assets of the communities and

- the influential factors that have an impact on these problems and also on needs and assets, with the desired results to be achieved by the program.2

FaHCSIA has developed its own program logic, and that can be found at Appendix C.

Figure 2. High-level concept map

Description of High-level concept map.

Influential Factors

- Extensive Review of the Northern Territory Emergency Response.

- Experience and feedback from people on other income management schemes (e.g. VIM, CPSIM, CY).

- Access to services.

- Knowledge of the range of policy levers that influence behaviour and outcomes for welfare recipients.

Knowledge

- Income management is one tool that may assist people to allocate their income more responsibly, and reduce their vulnerability and that of their dependents.

- Passive welfare creates a cycle of dependency.

- Income management can provide a gateway into other initiatives including building money management skills, and leverage for responsible parenting and participation.

- Focusing on priority needs allows issues such as food security, housing and children’s needs to be addressed.

- Previous income management arrangements were discriminatory and required the suspension of the Racial Discrimination Act.

Strategies

Implement income management to:

- ensure appropriate expenditure of income support payments on priority goods

- reduce the amount of income support that is spent on excluded goods

- reduce the amount of harassment, financial abuse and related pressures in relation to welfare payments and

- provide incentives and support for improved financial management skills and practices, workforce and educational participation, and responsible parenting.

Problems/issues for consideration

- Variation in opportunities for economic participation within communities.

- Entrenched welfare dependency and associated issues.

- Low levels of positive social participation and high degree of vulnerability.

- Inadequate spending on priority needs and other poor financial management outcomes including debt and arrears.

- Breakdown in community values and solidarity.

- Need to provide support for the most vulnerable in communities.

- Acknowledging the potential strength of some particular communities, including remote Indigenous Communities.

Desired results

- More spending on priority goods.

- Less spending on excluded goods.

- Reduction in immediate hardship of individuals and families.

- More responsible parenting and better outcomes for children, including nutrition and education.

- Increased financial management skills and capacity to save.

- Greater levels of positive economic and social participation and responsibility.

[ top ]

3.1 Objectives/rationale of NIM

Objectives for NIM have broadly been taken from Minister Macklin's second reading speech, and the Government's Policy Statement "Landmark Reform to the Welfare System, Reinstatement of the Racial Discrimination Act and Strengthening of the Northern Territory Emergency Response".

The Australian Government's Policy Statement (2009, p. 1) identifies the aims of new income management as to:

"...provide for the welfare of individuals and families, and particularly children…" by ensuring that people meet their immediate priority needs and those of their children and other dependents. Income management can reduce the amount of welfare funds available to be spent on alcohol, gambling, tobacco products and pornography and can reduce the likelihood that a person will be at risk of harassment or financial abuse in relation to their welfare payments.

"Governments have a responsibility – particularly in relation to vulnerable and at risk citizens – to ensure income support payments are allocated in beneficial ways. The Government believes that the first call on welfare payments should be life essentials and the interests of children."

"In the Government's view the substantial benefits that can be achieved for these individuals through income management include: putting food on the table; stabilising housing; ensuring key bills are paid; helping minimise harassment; and helping people save money. In this way, income management lays the foundations for pathways to economic and social participation through helping to stabilise household budgeting that assists people to meet the basic needs of life. We recognise that these are benefits which are relevant to Indigenous people and non-Indigenous people in similar situations."

The policy statement also identifies income management as a key tool in the Government's broader welfare reforms to promote responsibility and strengthen families by ensuring that income support payments are spent where they are intended.

Income management limits expenditure of income support payments on excluded items, including alcohol, tobacco, pornography, gambling goods and activities. It ensures that money is available for life essentials, and provides a tool to stabilise people's circumstances, easing immediate financial stress.

According to the program logic, this change in expenditure patterns is expected to result in a number of other benefits for children, parents and the broader community. A reduction in negative expenditures may result in reductions in alcohol fuelled violence, substance abuse and risky behaviour. The promotion of positive expenditure patterns may result in more effective meeting of children's needs including improved nutrition and increased spending on children's clothing and school-related expenses.

As a consequence of better spending on children, there may be improvements in positive health behaviours and improved educational attendance, which in turn could lead to improved educational outcomes.

In addition, the exemption criteria are intended to reinforce some of these positive outcomes. For example, families may be able to secure exemptions if their children are immunised and if they are attending school. Additionally, exemptions are available on demonstrating that children are engaged in activities such as structured, age appropriate social, learning or physical activities.

Overall, the program is intended to reinforce responsible parenting and more generally promote principles of engagement, participation and personal responsibility.

The Australian Government funds financial counselling services through the Financial Management Program (FMP), which was established to build financial resilience and wellbeing among those most at risk of financial and social exclusion and disadvantage. The Program helps vulnerable people across a range of income and financial literacy levels to manage their money, overcome financial adversity, participate in their communities and plan for the medium to long term.

This Program contributes to improved outcomes for vulnerable people, families, and communities by:

- fostering the improved use and management of money

- helping people address immediate needs in times of financial crisis and

- undertaking research to inform policies to reduce the impact of problem gambling.

The provision of financial counselling through FMP and the new incentives for saving could lead to improved savings and household budgeting, which in turn could result, for example, in the ability to purchase needed consumer durables. Better financial management is intended to assist families in meeting important bills such as rent and utilities, which could in turn stabilise housing and reduce risks of eviction and homelessness or sleeping rough.

It is also expected that certain sorts of child neglect could well be exacerbated by poor household financial management, for example, poor management may mean that children are hungry. It is also anticipated that income management will assist some individuals in resisting undesirable behaviour by their relatives and kin (i.e. harassment for money).

In broad terms, new income management is intended to set in motion a series of positive behaviours that will be mutually reinforcing. Outcomes are therefore expected to be:

- short-term (e.g. changed expenditure patterns—less expenditure on excluded goods, more expenditure on priority items)

- medium-term (e.g. take-up of referrals to money management and financial counselling service providers, improved educational attendance), and

- long-term (e.g. acquisition of money management skills, improved employment opportunities and improved educational attainment).

The potential impacts of the model are not only expected to be felt by the individuals directly affected, but the communities in which these individuals live are also expected to be affected.

As there will be movement onto and off the program, it will be necessary to consider outcomes not only for those who are currently participating in the model, but also for those who have left the model and are no longer having their benefits managed.

- This approach to the logic model reflects the Logic Model approach developed by the WK Kellogg foundation. This structural approach is further developed in the next section with regard to the identification of the key evaluation questions.

4. New income management evaluation framework

This section outlines the consortium's proposed evaluation framework. It is expected that some elements of this framework will be further developed by the independent evaluator as the project progresses.

This framework addresses scope of assessment, high-level research questions, study design, methodologies, proposed data (and sources) and an indicative timetable. Research Instruments and more detailed evaluation questions will be developed in Phase 2 of the evaluation project.

The main purposes of the evaluation activities to be conducted over the 2010-2014 financial years are to:

- provide evidence on the impact on NIM on those who are affected

- assess whether the reforms were implemented effectively, and

- understand whether NIM is a cost-effective model so as to inform future government decision making and social policy formulation for both the wider and the Indigenous communities.

4.1 Scope of assessment

The evaluation should contain a process evaluation, an outcome evaluation and a value for money analysis. This evaluation strategy has been informed by a comprehensive literature review of evaluations of similar conditional welfare programs internationally (see Appendix E).

4.2 Process evaluation

The process evaluation should examine how NIM was implemented and should report on the barriers and enablers which affected its implementation. (See Section 5 for more detail).

4.3 Outcome evaluation

The outcome evaluation should assess the impact of the model at the individual, family/household and community level in the Northern Territory. The evaluation should draw on administrative data, survey data, longitudinal interviews and case studies to determine the extent of individual, family/household and community level changes over 2010-14 financial years.

Regular reports should be delivered to FaHCSIA by end of each calendar year from 2011-2014, including:

- a substantial progress report addressing implementation issues and early progress in achieving short term outcomes, by the end of 2011

- annual intermediate evaluation reports that synthesise results to date and inform future analysis, by the end of 2012 and 2013, and

- a final outcome evaluation report by the end of 2014 (See Section 5).

Interim evaluation reports (short-medium term outcome evaluations) should be conducted on an annual basis and be delivered by end December 2011-2013 – see Sections 5 and 6 for more detail. The final evaluation report will be delivered by the end of December 2014 and contain information on the short-medium, and wherever possible longer-term, outcomes along with value for money analysis3. See Section 4.4.2 for more detail.

With regard to the evaluation questions and indicators, the evaluation will seek to provide answers to the following high level questions. At this stage, the questions are broad and there is a need to further develop specific research questions in Phase 2 of this project.

[ top ]

4.4 Broad overarching questions across all four streams of new income management (ie participation/parenting, child protection, voluntary and vulnerable streams)

4.4.1 Process evaluation

- How effectively has NIM been administered and implemented?

- What have been the resource implications of implementing the program?

- Have suitable individuals and groups been targeted by NIM?

- Have people been able to transfer into and out of NIM appropriately (e.g. choosing to transfer from income management under NTER to VIM)?

- What has been the effect of the introduction of NIM on service providers?

- What is the profile of people on the different income management streams?

- Have there been any initial process 'teething issues' that need to be addressed?

- What are the views of participants in the NIM model and their families on the implementation of the program?

- Has the measure been implemented in a non-discriminatory manner?

4.4.2 Outcome evaluation

- What are the short, medium and longer-term impacts of income management on individuals, their families and communities?

- How do these effects differ for the various streams of the program (mainstream, voluntary, child protection, vulnerable)?

- Have there been changes in spending patterns, food and alcohol consumption, school attendance and harassment?

- What impact does NIM have on movement in and out of NT among people on the measure?

- Has NIM contributed to changes in financial management, child health, alcohol abuse, violence and parenting (ie reduced neglect)?

- Do the four streams achieve appropriate outcomes for their participants?

- Has NIM had any unintended consequences (positive or negative)?

- Are there differential effects for different groups? (including—if sufficient data is available—by Indigeneity, gender, location, age, educational status, work status, income, length of time on income support, marital status, family composition and diverse cultural and linguistic background)

- Does IM provide value for money by comparison with other interventions?

- Does NIM provide any benefits over and above targeted service provision?

[ top ]

4.5 Research questions for specific streams of the NIM model

4.5.1 Questions specific to the participation/parenting stream

- Has NIM helped to facilitate better management of finances in the short, medium and long term for people on income management and their families?

- Has access to services or interventions improved for those families?

- Have other changes in the wellbeing and capabilities of the individuals and families occurred?

4.5.2 Questions specific to the child protection stream

- What has been the impact of income management on child neglect?

- What has been the impact on child wellbeing in those families referred to the child protection measure (CPIM)?

- What are the barriers and facilitating factors for child protection workers to use income management as a casework tool?

- What (if any) service delivery gaps have impacted on the usefulness of the CPIM?

4.5.3 Questions specific to the vulnerable stream

- Are vulnerable people appropriately targeted by this measure?

- How does income management impact on the vulnerability of individuals?

- Have people on this stream experienced changes in the level of harassment (e.g. humbugging)?

4.5.4 Questions specific to the voluntary stream

- Have people who volunteered for income management been able to make an informed choice?

- How long do voluntary income management recipients stay on the measure?

- What are the key motivations for people who voluntarily access income management, and why do they stop?

- An analysis of value for money should assess the cost effectiveness of new income management. The cost effectiveness analysis will use the quantitative data from the outcome evaluation and financial data from programs to assess the extent to which the costs produced tangible benefits.

5. Study design and methodology

5.1 Challenges in evaluating new income management

There are a number of conceptual and practical challenges to evaluating this measure.

5.1.1 Conceptual challenges

Attribution

Separating the impacts of NIM from those of other policies and programs is challenging. NIM is being implemented as part of a range of intersecting Commonwealth and Territory social policy initiatives which will have an impact on individuals and communities. Examples include policies related to alcohol restrictions, school nutrition and attendance programs and a range of other health initiatives. There may also be changes to other policies during the evaluation period.

From an evaluation perspective a central challenge will be to differentiate the impact of income management from these other programs and interventions, as well as identifying both positive and negative interdependencies between these.

Nature of expected changes

NIM has a number of short, medium and long-term objectives at the individual and population levels and it will be very difficult to disaggregate these different outcomes at different levels.

Service availability and quality

NIM is predicated on the assumption that participants will use their income to benefit their children and improve their lives. In order to do so they must avail themselves of a range of services and opportunities including purchasing healthy food, sending their children to school and having their health checked, attending financial counselling, attending TAFE and seeking work. However if there is limited or no availability of some of these services or opportunities then this will undermine the effectiveness of the model, and will greatly reduce the likelihood of positive outcomes. The quality of services, including the skills and qualifications of workers and level of adherence to policy guidelines, may also impact on service outcomes. The identification of service delivery gaps, however, may prove to be a useful finding within itself, in terms of informing future policy development. The evaluation will therefore need to separate the effects of income management itself from the effects of the services associated with the model, in particular financial counselling.

5.1.2 Practical challenges

A significant number of individuals being income managed will be vulnerable and it may be challenging to engage them in the evaluation.

Data will need to be collected from income management participants from diverse backgrounds and living in very different areas (e.g. cities, town and remote communities) and the data collection instruments will need to be able to cope with the diversity of those being income managed.

- Data will need to be collected from those living in remote communities and those delivering services in remote communities. This creates logistical challenges.

- A substantial proportion of those being income managed (particularly in the Northern Territory) will be Indigenous. There are particular issues and challenges in collecting information from Indigenous Australians. The research ethical issues involved are discussed in Section 7.

A number of further complexities should be noted. As described in Section 2, there are four major groups directly affected by the new income management:

- those who are compulsorily managed because of the type of benefit they are receiving and their duration of benefit receipt (participation/parenting stream)

- those who are managed because a Centrelink social worker believes them to be particularly vulnerable (vulnerable stream)

- those who are referred by child protection authorities (child protection stream), and

- those who volunteer for income management (voluntary stream).

There are a number of different pathways people can take between the different types of income management. For example, people could move from Child Protection of Income Management (CPIM) to Voluntary Income Management (VIM) and VIM to CPIM. See Figure 1 on page 7 for more detail.

In addition, those affected can be categorised in relation to their previous exposure to income management. There will be people who were income managed under the NTER, because of the location in which they live, and those who are being income managed for the first time. Additionally, in the non-income managed population there will be people who have never had their income managed, as well as those who were previously managed but are no longer subject to the measure, such as Age Pension and Disability Support Pension recipients living in locations where income management was previously applied.

It is also important to note that the schematic program logic shown above could be expected to differ between the three main groups identified earlier. That is, the program logic for people who are income managed because of concerns about child neglect will differ from the logic for people who are income managed because of the type of benefit that they receive and their duration on that benefit. Both of these program logics will differ from that for people who volunteer for the program. It seems plausible that people who volunteer for the program will be more motivated to engage with income management and, therefore, are likely to have better outcomes than people whose incomes are compulsorily managed. Similarly, it might be anticipated that people who are income-managed due to referrals from child protection authorities may well have less favourable outcomes.

In considering the program logic outlined above it is also essential to bear in mind that outcomes for those who are income managed will reflect much more than the effects of the program. The overall context in which income management occurs is of crucial importance. General economic circumstance such as changes in unemployment can have major effects on outcomes for income-managed individuals. Similarly, if fresh fruit and vegetables are simply too expensive to be met out of current benefit levels for NT residents living in remote areas, or if housing costs are too high in some locations to be adequately met with existing rent assistance, then outcomes could well appear negative even if the program itself actually had a positive impact. In addition, there are likely to be other changes in policy from the Commonwealth or the State or Territory government that could impact on outcomes for people who are income managed and the communities in which they live, for example, unrelated changes in benefit policy, health policy, education policy, housing policy or child protection policy.

A further complicating factor is that individuals who are income managed under the new model will have a range of differing family circumstances that will affect the outcomes of the model. In some cases families or wider kinship networks may pool resources to assist those who are income-managed, which could either reinforce or undercut the objectives of the model, while other individuals may not have this form of family support.

These considerations suggest that it will be necessary to take a broad approach to defining outcome variables – that is, the preferred evaluation approach should identify both the key outcomes that are intended by the new income management but place these in a broader context that can capture the impact of changes in the general environment and other policy changes.

The design will use both qualitative and quantitative methods to answer the research questions. It is not possible to use an experimental design, and therefore the outcomes will have to be determined by triangulating data from different sources.

5.2 Data sources

An important and necessary component will be the collection of data needed to support the evaluation. A thorough data audit, conducted by the consortium, indicates that significant data gaps exist. Many of those datasets that do exist are either not very reliable, not easily available for small geographic areas or are difficult to access for various reasons.

The evaluation should utilise a variety of data sources. This reflects the particular characteristics of the program and the outcomes that are being measured. The use of a diverse set of data sources also allows the evaluation to be conducted in a multi-layered way, taking account of the reported experience of individuals, administrative information on this, and the perspective of those involved in the implementation of the program. It also permits the ‘triangulation' of particular outcomes which may be difficult to measure. A mixed-methods evaluation is proposed that draws together information from multiple sources.

The evaluation of NIM will need to draw on data from a number of sources. This section provides an overview of these sources. The data that are needed fall into four types:

- administrative by-product data (also termed system data) from governments

- system data from private enterprises (eg. retail sales)

- purpose-designed data collected from people on NIM, those involved in implementing the model and the broader community, comprising both:

- individual surveys utilising a range of approaches appropriate to the circumstances of different groups, and

- qualitative data collection through interviews, focus groups and other mechanisms.

- existing survey data.

5.3 Timing of different components of the evaluation

The evaluation should be undertaken in two stages. Stage one is the development of the evaluation framework including the scope and methodology of the evaluation, and establishment of the methods and data collection. Stage one includes an early implementation snapshot study of service providers in the NT to establish their readiness to implement NIM, as well as surveys of income managed clients to capture benchmark data that reflects circumstances of individuals, families and communities soon after the implementation of NIM.

Stage two will include two sub stages; the first stage will involve providing a process evaluation report to FaHCSIA by December 2011. This report will focus on the implementation of NIM and the barriers and facilitating factors to implementation. It will also include the views of a range of stakeholders and indications of short term outcomes including transitions to IM, exemptions, service availability and store data.

The second sub phase will focus on the short, medium and, where possible, longer term impacts of NIM on people, their families and communities. Intermediate evaluation reports that synthesise results to date and inform future analysis should be delivered to FaHCSIA by the end of 2012 and 2013. The final outcome evaluation report should be provided by end of 2014.

This graphic shows the deliverables due throughout the project, along with the activities that will occur at each stage. The deliverables are:

- December 2011 = Intermediate Evaluation Report (process)

- December 2012 = Intermediate Evaluation Report (Process & short term outcomes)

- December 2013 = Intermediate Evaluation Report (Short & medium term outcomes)

- December 2014 = Intermediate Evaluation Report (Final Outcome Evaluation Report

Ongoing data collection/information gathering will occur throughou the project.

Implementation Snapshop study will occur between August 2010 and December 2011.

Other inputs as required will occur from December 2011 until Decenber 2014.

5.4 Geographic analysis

We recommend that a key component of the impact evaluation be an ecological analysis describing the association between the prevalence of income management and key outcome variables aggregated across small to medium geographic areas.

Whether this analysis will be suitable for the examination of long-term outcomes will depend upon the extent to which people move between different locations. An examination of Centrelink administrative (and possibly Census) data on mobility patterns will thus need to be undertaken as a complementary component to this analysis.

The main motivation for this is that information on many of the key outcome variables such as expenditure patterns are difficult to collect at the individual level for those participating in the program and even more difficult to collect for comparable people not participating (or for participants prior to their participation). Moreover, there is intrinsic interest in community level outcomes.

The methodology proposes that aggregate information be collected for regions across the NT (and possibly other States) around the implementation period, including on:

- the proportion of the population (or some relevant sub-population) participating in NIM (or some aspect of NIM)

- outcome variables (e.g. expenditures, crime rates, child wellbeing outcomes) and

- confounding variables (such as the operation of other programs).

The correlation between the NIM participation rate and the outcome variables is examined while controlling for confounding variables. If data over time are available, fixed-effect models can be used which examine the changes in NIM and outcome measures in each region.

The main threat to the validity for this analysis, as with all non-experimental analyses, is that there may be unobserved differences across regions which are correlated with both the outcome variables and NIM participation. For example, areas which have a high proportion of the population moving onto NIM might also experience a large increase in other interventions at the same time. If this is not also measured and controlled for the observed association will be a biased estimate of the impact of NIM on outcomes.

Similarly, the cessation of the old model of income management will need to be controlled for (or might form an intervention variable to be analysed in its own right). The associated threat to the reliability (or precision) of such an analysis is that, once all these potential confounders are controlled for, there may be insufficient independent variation in the NIM participation variables to enable comparison of different levels of NIM. Whether this will be the case is difficult to ascertain prior to data collection. A necessary requirement for the geographic analysis described here to be informative is that there be sufficient geographic variation in the changes in NIM participation over time. The first exploratory stage of the geographic analysis would thus be to analyse the geographic spread of income management participation patterns using the Centrelink administrative data.

For example, even if the NIM is rolled out at the same time to all regions of the NT, there will be some regions where a large proportion of the population is subject to this program, and other areas where the proportion subject in the population is small. If favourable changes in the outcome variables are observed in the former areas but not the latter, then this will provide strong evidence on the efficacy of the model.

Because most components of the NIM will vary together at the regional level, this impact analysis will be most suited to measurement of the overall impact of the NIM program, rather than particular components.

Note that it is intrinsically impossible in this analysis to separate the impact of the NIM model from other variables which vary closely along with it. For example, NIM is targeted at particular disadvantaged groups. In the case described in the previous paragraph, one cannot rule out that the observed association will be due to these groups doing better for some unexplained reason or because of another intervention. The research can only be made more robust by seeking to understand the impact of all the potential confounding factors.

The following considerations should guide the collection of data for this exercise.

5.5 Geographic scope

Ideally, the scope for this exercise should include comparable areas outside of the NT which have not been subject to IM. Data extraction from Commonwealth data collections should be designed with this intention in mind. However, many of the key outcome variables are only available via State government departments. These variables may be both defined differently and available for analysis in different forms in different States – which might thus require a restriction to the NT. Nonetheless, if it is envisaged that NIM will be generalised to other states and territories, collecting data from these jurisdictions now may form the grounding for future evaluations of those programs.

5.6 Time scope

The data should preferably cover the time period starting several years before the NIM implementation to a period after NIM is well-established and bedded down.

5.7 Regional aggregation

The data for the outcome variables should be collected at as small a regional level as possible, consistent with the relevant catchment areas for the different outcomes. For example, for alcohol expenditure, a suitable unit might be a township or a suburb. In both cases there might be spill-over effects into adjoining regions, but this can be modelled in the data analysis if the initial data collection is at a suitably low level of aggregation.

Similarly, data on migration between the regions can be incorporated into the modelling exercise. The most useful data for this will be Centrelink data on location patterns of the whole client base – not just those involved in NIM.

The different outcome variables will generally be available at different levels of aggregation. It is therefore important that the geocoding in the NIM data be as detailed as possible so as to permit the creation of NIM participation estimates at levels of aggregation that match the different outcome variables.

5.8 Take-up and participation in new income management

If geo-coded data on NIM participation is available, this can then be compared with Census and other estimates of small area populations to estimate the NIM participation rate in each area over time.

5.9 Confounding factors

The key confounding factors to be considered will be the presence of other policy interventions in the different areas. Detailed information on these will need to be included in the modelling. See Appendix G: List of funded initiatives in the NT that support vulnerable children and families.

5.10 Sub components

As NIM contains four types of participants (mainstream, vulnerable, voluntary and child protection), the framework will seek to address each group separately. This is particularly true for the child protection component which not only potentially serves a different group of people, but also has very different entry and exit processes. Although the data for the sub-components will overlap, it is important to disaggregate these components in the analysis to ensure that the appropriate processes and outcomes for each group are treated separately.

5.11 Evaluation of the child protection measure in NT

Evaluation of CPIM will require some specific data collection. Data will need to be collected from child protection workers in the form of either in-depth interviews or focus groups.

It is also proposed that a case file review be undertaken and coded according to a pro forma. This methodology is particularly effective for creating de-identified data from confidential client files.4 It is proposed that a case file review be conducted to evaluate the impact of CPIM on child protection outcomes (e.g. re-notification, re-substantiation, substantiated type abuse and primary presenting problems).

The evaluation will examine data provided by the NT Government, which will track those families who have been referred to CPIM. The NT Department of Health and Families will provide information on:

- incidents of child protection notifications

- category of child protection notification (e.g. neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse or emotional abuse)

- whether or not the notification resulted in investigation by a caseworker

- whether or not reports were substantiated

- broad identifier of the reporter type (e.g. hospital, family, policy, school) and

- number of the child's encounters with youth justice system.

The Child Protection records of each child whose family is referred will also be examined for up to a 5-year period preceding the referral, in order to establish whether income management results in changes in re-notification rates for families. Information will also be collected about the service use of these families including:

- What other support services has the family been referred to?

- What other services has the family accessed or failed to access?

The NT Department of Health and Families (DHF) caseworkers will also be surveyed via online electronic surveys which can be completed in various sessions over a period of time (e.g. several weeks) to allow for workload management. These surveys will be similar to those of Centrelink workers and other stakeholders, and will cover their attitudes to IM, training, relationships with other agencies and barriers and facilitating factors to helping families who neglect their children.

In addition to these data about the families, more qualitative information will also be sought via the child protection caseworkers, including:

- children's access to adequate food, clothing, education, health services, notifications and stability of living arrangements and

- parents' attitudes, financial management skills and confidence, levels of stress, knowledge of IM, exposure to harassment.

- AIFS has successfully used this approach in evaluating the Magellan program and the 2006 changes to the family law system.

6. Ethics guidelines and ethical clearances for the evaluation of new income management

6.1 Ethics guidelines

The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) has a set of advice and guidelines on ethics and related issues in the fields of health and human research. The evaluation should be undertaken in accordance with these guidelines and should, in our view, be approved by a Human Research Ethics Committee which is registered with the Australian Health Ethics Committee. In addition, when working in the NT approval may be required from the relevant NT ethics committees.

A significant portion of evaluation participants are likely to be of Indigenous background. The NHMRC guidelines include guidance for conducting research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.5

In undertaking research with Indigenous people, particular attention needs to be paid to ensuring that participation is both informed and voluntary. Consideration needs to be given to the values underlying ethical research with Indigenous people - reciprocity, respect, equality, responsibility, survival and protection, spirit and integrity-across all aspects of the research process, including:

- consultation and negotiation

- mutual understanding of the purpose of the research

- the use of culturally appropriate instruments

- use of and access to research results, and

- communication of findings at a local level.

Consultation should begin prior to the commencement of the research and occur as an ongoing process throughout the evaluation. Consultation should be premised on respect, negotiation, and informed consent. Individuals and communities may need time to consider a proposed research project and to discuss its implications. Consultation and negotiation should achieve mutual understanding and agreement about the research’s aims, methodology, and implementation, as well as the use of the results it produces.

It is important that the consultation and negotiation process is not considered merely an opportunity for researchers to tell the community what they, the researchers, want. Indigenous knowledge systems and processes must be respected and acknowledged. Research in Indigenous studies must show an appreciation of the diversity and uniqueness of people and individuals. The intellectual and cultural property rights of Indigenous people must be respected, preserved, and acknowledged. Indigenous researchers, individuals and communities should be invited to be involved in research directly and as collaborators.

Appendix A: Earlier initiatives, background to the development of new income management

Since 2007, the Australian Government has been progressively developing a national reform agenda in relation to welfare recipients in disadvantaged regions and in relation to dysfunctional families and communities. Measures implemented include:

- Income Management in the Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER)

- Child Protection Scheme of Income Management (CPSIM)6

- Voluntary Income Management (VIM)

- Cape York Welfare Reform (CYWR)

- Improving School Enrolment and Attendance through Welfare Reform Measure (SEAM).

Each measure uses a combination of different tools to achieve its goals, including income management or increased conditionality on the receipt of income support. These measures are briefly described in the remainder of this section.

A1. Income management in the Northern Territory

Income management was first introduced as in the NT as part of the Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER), announced in June 2007, to promote socially responsible behaviour and help protect children. Legislation was passed in August 2007 to enable income management.

The initial roll-out of income management only affected people (Indigenous and non-Indigenous) who received income-support payments and who lived in 73 prescribed communities, their associated outstations and 10 town camp regions of the Northern Territory.

Under the NTER model of income management, half of people’s welfare payments were set aside for the priority needs of individuals, children and their families. Income-managed funds must have been directed towards agreed priority needs and services such as food, rent and utilities. Income-managed funds could not be used to purchase excluded items such as alcohol, tobacco, pornography or gambling products.

The objective of the NTER income management measure was to ensure that:

- money paid by the government for the benefit of children is directed to the priority needs of children

- women, the elderly and other vulnerable community members are provided with better financial security and

- the amount of cash in communities is reduced to help counter substance abuse, gambling and other anti-social behaviours that can lead to child abuse and community dysfunction.

A2. Child protection scheme of income management (CPSIM)

The Commonwealth and Western Australian Governments are working together to implement a trial of CPSIM in Western Australia. A bilateral agreement supports this trial. Under this initiative, the Western Australian Department of Child Protection has the option of requesting that Centrelink manage an individual's income support and family payments in cases where poor use of existing financial resources is wholly or partially contributing to child neglect or other barriers the individual may be facing.

The Commonwealth Government has responsibility for income support and family payments and is therefore able to link certain conditions to these payments; however broader responsibility for child protection remains with the Western Australian Government.

CPSIM was implemented in specific Western Australian locations from November 2008 and has been progressively rolled out to the Kimberley region, and particular Department for Child Protection districts of metropolitan Perth.

As in the Northern Territory, income management involves Centrelink directing income support and family payments to meet priority needs such as food, clothing and housing. Income managed funds cannot be used to purchase alcohol, tobacco, pornography or gambling products.

Support services are offered to assist those on income management and include financial management services provided through FaHCSIA and Parent Support services provided through the Department of Child Protection. Appendix B provides an overview of current evaluation activities of this measure.

A3. Voluntary income management measure (VIM)

VIM was implemented in conjunction with CPSIM in Western Australia in late 2008. This initiative allows income support recipients in particular districts in metropolitan Perth and the Kimberly region to volunteer for income management to assist them to meet their priority needs and learn tools to help manage their finances for themselves and/or their family in the long term.

Individuals who are placed on VIM also receive a referral to financial counselling or financial education services funded by FaHCSIA. Appendix B provides an overview of current evaluation activities of this measure.

A4. Cape York welfare reform (CYWR)

A different approach to welfare is being trialled in the Cape York communities of Aurukun, Coen, Hope Vale, and Mossman Gorge and associated outstations. Cape York Welfare Reform is a partnership between the four communities, the Australian Government, the Queensland Government and the Cape York Institute for Policy and Leadership. The reforms, which will run from 1 July 2008 to 31 December 2011, aim to create incentives for individuals to engage in the real economy, reduce passivity and re-establish positive social norms.

Under the reforms, an independent statutory body called the Family Responsibilities Commission (FRC) has been established to help rebuild social norms in the four Cape York Welfare Reform communities. Components include referring individuals to support services and possibly to income management. Fifteen programs covering housing, education, social responsibility and economic opportunity are being rolled out as part of the reforms. Appendix B provides an overview of current evaluation activities of this measure.

A5. Improving school enrolment and attendance through welfare reform measure (SEAM)

SEAM aims to increase the enrolment and regular attendance at school of school-age children whose parents are receiving a schooling requirement payment7 by placing conditions on the parents' receipt of such payments to ensure their children are enrolled at and attending school on a regular basis. Parents who do not comply may have their schooling requirement payment suspended until they do comply. Other payments such as FTB and CCB continue to be paid during a SEAM suspension period.

SEAM does not reduce the primary responsibility of state and territory education authorities to respond to truancy issues. Rather, it is intended to provide an additional tool to help resolve intractable cases of no enrolment or poor attendance. SEAM includes a pathway to parenting resources for those parents who need assistance through Centrelink support and referrals to relevant services.

SEAM responds to the finding that an estimated 20,000 Australian children of compulsory school age are not enrolled in school, with many others not attending regularly. SEAM encourages parents to ensure that their children are enrolled at and regularly attending school by linking enrolment and attendance to parents' welfare payments. SEAM uses possible suspension of income support payments, supported by a case management approach, to encourage responsible parental behaviour. In extreme cases income support payments may be cancelled, but this is expected to be a very rare occurrence.

SEAM trials commenced from the beginning of the 2009 school year in six locations in the Northern Territory: Katherine, Katherine Town Camps, Tiwi Islands, Hermannsburg, Wadeye and Wallace Rockhole. The Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) has the responsibility for evaluating this measure.

- As part of the Australian Government’s commitment to improving outcomes for vulnerable and disadvantaged Australians, the Child Protection Scheme for Income Management (CPSIM) in Western Australia has been extended for a further year. Voluntary Income Management (VIM) is also offered in WA. Under the new income management measure in NT, the CPSIM is referred to as the Child Protection Measure (CPM). This reflects the subtle differences between the two compulsory measures designed to help Child Protection Authorities in WA and NT to help vulnerable families.

- Schooling requirement payments are defined in section 124D of the SS(Admin)Act. They include social security benefits and pensions as defined in section 23 of the SSAct as well as 3 payments under the Veteran’s Entitlement Act 1986 (VEA).

Appendix B: Current income management evaluation activities 8

B1. Findings from the evaluation of the child protection scheme of income management and voluntary income management measures in Western Australia

The Australian Government implemented a trial of two separate models of income management in the Kimberley and Cannington regions in WA starting in November 2008. The evaluation of these trials, led by FaHCSIA and supported by WA Department of Child Protection (DCP), was undertaken by ORIMA Research Pty Ltd. The report was publicly released by the Minister on 8 October 2010 and can be found can be found on the FaHCSIA website.

The evaluation was designed to assess:

- the impact of income management in improving child wellbeing

- the impact of income management on the financial capability of individuals and

- the effectiveness of the implementation of income management.

The evaluation findings are based on various data sources including:

- quantitative data collected from surveys of people on VIM and CPSIM, and the comparison group9

- online surveys of Centrelink and DCP staff, as well as financial counsellors, money management advisers, WA peak welfare sector bodies and community organisations with an interest in income management

- administrative data from Centrelink, WA DCP and financial management service providers and

- qualitative data based on focus groups and interviews conducted with community leaders in the Kimberley area.

Since the start of trials of income management in WA in November 2008 to 30 April 2010, there has been a total of 1,131 people in receipt of Centrelink payments who have participated—328 who have been referred to income management by the WA DCP and 803 who have volunteered for income management. At 30 April 2010, there were 598 people on income management—226 people on CPSIM and 372 people on VIM. See Figure 1, below.

Figure 1: Number of current CPSIM and VIM participants (28 November 2008 to 30 April 2010)

Figure 1 identifies the number of current child protection income management and voluntary income management customers as of 28 November 2008 to 30 April 2010.

The graph illustrates that the number of voluntary income management customers is larger than those on the child protection measure, with both measures experiencing steady increases in customer’s number from 28 November 2008 to 30 April 2010.

B2. General findings

Overall the evaluation report suggests that income management had made a positive impact on the wellbeing of individuals, children and families. Moreover, since the introduction of income management, CPSIM respondents reported decreases in a range of negative behaviours in their communities.

There was an initial perception that compulsory income management (including CPSIM) would not be as well received or as able to achieve the best outcomes for individuals as would a voluntary scheme of income management (VIM). However, contrary to the common view that compulsory schemes, such as the Child Protection Scheme of Income Management (CPSIM), are not as effective as voluntary schemes, the evaluation findings showed that that both voluntary and child protection measures are having equally positive effects on the wellbeing of families in WA. Around 62 per cent of people on CPSIM and 60 per cent of people on VIM thought that income management had made their life better.

A further breakdown reveals that more people on the VIM scheme (51 per cent of people surveyed) than the CPSIM (34 per cent) felt that income management had made their lives “a lot better”. The remainder felt that income management had made their lives “a bit better” (9 per cent for VIM and 28 per cent for CPSIM).

This finding is reinforced by the willingness of both people on CPSIM and VIM to recommend income management to others. Sixty-five per cent of CPSIM and 82 per cent of people on VIM reported that they had already recommended income management to someone else or planned to do so in the future. (A similar sentiment appears evident in the NT where early indications in the Barkly area show that 75 per cent of those who could have exited from the new income management scheme chose to remain on VIM).

There were three main reasons why people on income management had recommended or intended to recommend the scheme:

- income management can have a positive impact on people’s lives

- income management helps improve budgeting skills and saving money and

- due to the benefits associated with the BasicsCard.

The report also identified areas for improvement in terms of the income management schemes. There was a low level of awareness among people on income management as to the proportion of funds that was being managed and the reasons they were subject to income management. The report also revealed a need to increase the number of merchants that are approved to accept the BasicsCard and a need to improve communications to people on income management. The most commonly reported potential negative outcome was that some people might become dependent on income management.

B3. Specific findings

There was an increase in the percentage of people able to buy essential items and meet priority needs, and an increased ability to save money on a regular basis. Around 74 per cent of respondents reported that they had been unable to pay for at least one essential item (such as food, utilities, rent, bills and so on) in the 12 months prior to commencing income management. However, during income management the proportion of people unable to pay for such items decreased by 25 per cent.

After exiting income management, many people reported that their increased ability to meet their own, and their children’s, priority needs that occurred whilst they were on the scheme continued and, in some cases, improved. Figure 2 below shows the proportion of people on CPSIM who ran out of money to pay for an essential item category before, during and after (in the case of people formerly on CPSIM) income management participation. During the income management period, both current and people who were formerly on CPSIM were less likely to run out of money for food, utilities, rent and other bills.

Whilst on income management (and compared with when they were not on income management), CPSIM respondents were most likely to report that the following positive impacts had emerged:

- they and their children had eaten less takeaway food (56 per cent and 55 per cent respectively)

- their children had eaten more food (54 per cent)

- they and their children had eaten more fresh food (53 per cent and 48 per cent respectively)

- they had purchased more clothes for their children (53 per cent) and

- they had purchased more toys for their children (48 per cent).

Figure 2: Proportion (per cent) of people running out of money for essential items, by item type: before, during, and after income management

Figure 2 illustrates the proportion of people running out of money for essential items before, during and after income management

Before income management, 59% of respondents were running out of money for food. During income management, this percentage dropped to 29%. After income management only 16% of people were running out of money for food.

Before income management, 40% of respondents were running out of money to pay utility expenses. During income management, this dropped to 9% of respondents.

Before income management, 31% of respondents were running out of money for the children’s education. During income management, this dropped to 14%. After income management, the percentage of people running out of money for children’s education increased to 21%.

In terms of their ability to save money, around 70 per cent of CPSIM and 80 per cent of VIM respondents reported that they were regularly able to save money when they were on income management. This is a significant increase from 51 per cent and 54 per cent respectively before being involved in the income management scheme.