Review of the respite and information services for young carers program Final Report – Stakeholder Summary

Attachments

Contents

- Foreword and Acknowledgments

- Executive summary

- Introduction

- Review methodology

- Implementation of respite component of the Program

- Implementation of the information, referral and advice service

- Outcomes for young carers

- Funding

- Performance measurement

- Modifications to the Program

- Appendix 1 – Project Reference summaries

- Appendix 2 – Summary of similar programs

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

Foreword

This report is a summary of the final evaluation report by ARTD Consultants of, what is now titled, the Young Carers Respite and Information Services Program. It was prepared by the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs to inform stakeholders about key findings and for feedback about how the program is being delivered nationally.

Following the evaluation, many changes were implemented for the 2008-09 financial year, including revised program guidelines and reporting requirements.

Our thanks to all those who participated in the evaluation and to ARTD Consultants for their valuable work.

Acknowledgements

This work was commissioned by the Australian Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs.

We would also like to thank the young carers who participated in the review, and the many key stakeholders from Commonwealth Respite and Carelink Centres and Carers Australia. We thank them for their time and insights and trust that their views are adequately represented in this report.

ARTD Consultancy Team

Wendy Hodge, Kerry Hart, Marita Merlene, Ofir Thaler and Carlo Jacobson.

Executive summary

This report presents the findings of an independent evaluation of the Respite and Information Services for Young Carers Program. The Young Carers Program has been implemented for three and half years (January 2005 to June 2008) with funding of $26.6M from the Australian Government Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA).

The evaluation was conducted by ARTD Consultants, from October 2007 to March 2008 and is intended to inform the future directions of the program.

The Respite and Information Services for Young Carers Program (Young Carers Program)

The Young Carers Program aims to assist young carers by supporting them to stay in education or training while continuing in their caring role. The program targets young carers who are completing their secondary education or the vocational education equivalent and are at risk of leaving school prematurely because of their caring role. Young Carers are defined as being at risk where, due to the caring responsibilities, they: frequently miss school; have no time to complete homework; feel very distracted when they are at school and experience limited connectedness with their school community and are considering leaving secondary school or equivalent education prematurely.

The program has two separate but related components: respite services delivered by Commonwealth Respite and Carelink Centres (CRCCs), located in 55 Home and Community Care (HACC) regions across Australia; and information, referral and advice services delivered by Carers Australia and their member Carers Associations.

Evaluation methodology

The evaluation used a mixed methods approach combining qualitative case studies at ten sites across Australia (identified by State and Territory Offices as operating well); feedback from relevant stakeholders; a quantitative survey of Commonwealth Respite and Carelink Centres (CRCCs); and an analysis of documents and monitoring data reported in Carers Australia Quarterly Reports (2006/ 2007) and CRCC Quarterly reports for first quarter of 2007/2008.

In all, the ARTD consultancy team interviewed 82 program stakeholders sourced from CRCCs, Carers Australia and other local providers and agencies, and conducted three discussion groups at state network meetings of CRCC staff. ARTD researchers also visited eight CRCCs and two State Carers Association services.

We also consulted 91 young carer clients of CRCCs and Carers Australia through ten focus groups and 23 phone interviews.

The methodology was able to be applied effectively, but caution is needed in interpreting the results for young carers, in particular because of the positive bias introduced by sampling young people in contact with effective services or actively involved in Carers Associations networks. In addition, we are missing implementation data on 24% of CRCCs.

Key findings

The Young Carers Program is an important program which provides services that are not readily available through alternate services.

Where young carers used the services for respite, information, referral and advice, they reported gaining important emotional and social benefits as well as being assisted to cope with their caring responsibilities and school work.

The Program was implemented as a traditional direct respite, information, advice and referral program, targeting young people which did not take into account the special circumstances and respite needs of young carers. As a result, some CRCCs adapted the service model to better meet the needs of young people, providing a flexible and broad range of indirect and direct respite services. Other services, particularly rural and remote CRCCS, struggled to implement the program.

Respite services

The respite services component met its target of assisting approximately 750 young carers a year, for the last two years of implementation. By the second year of the program, 1,100 young carers used respite services across Australia, up from an estimated 720 in the first year. Most young carers receiving assistance fit the main target group being high school age, 12 to 17 years. Nevertheless, 12% of young carers using services are primary school age and 5% are aged 22 to 25 years. Almost half of young carers using respite services have significant caring responsibilities, caring for a parent with a mental illness, a chronic illness or a disability. Many face complex family situations.

Implementation of the respite services has been characterised by diverse approaches and levels of commitment, driven by the poor fit between the service model framed in the Guidelines and the expressed respite needs of young people. CRCCs have faced difficulties identifying and accessing young carers and sometimes working with this unfamiliar client group. An important finding for the Review is that programs working with ‘hidden carers’, such as young people, need to provide sufficient resources towards raising the profile of carers in the wider community and also to services to find and access these carers. The operational/ brokerage split worked against such activity.

Service delivery has evolved over time to include outreach strategies, case management and a focus on indirect services, rather than direct services, although their direct respite does provide valuable assistance in specific circumstances. In practice, direct respite was only occasionally suitable for young people, and other services proved to be both more acceptable to young people and to offer a respite effect. Although young people appreciate the range of practical support in home and with school work they most value the personal support and advice they get from the service workers, whether they are based in CRCCs or State Carers Associations. Choice of respite options and flexibility in service delivery are key principles in providing effective respite services for young people.

CRCCs are working with other government agencies to provide support to young people. Workers may simply share information during meetings and/ or make cross-referrals and/ or coordinate support for the young person. Links may be through formal partnerships or informal relationships at the worker level, depending on the service model used by the CRCC. Examples of collaborative partnerships we found are with mental health services, Centrelink, youth services and schools.

Developing links with other services is an important strategy in planning for ongoing support for the young carer, particularly with the increasing complexity of referrals as the program becomes better known. Schools and health agencies have emerged as key referral agencies and the evidence shows there remains substantial work to be done to get the welfare of young carers to be recognised more broadly amongst school staff and health workers. Systems based approaches at the departmental level to direct policy and practice at the local level are necessary to bring about broad-based change.

Information, advice and referral services

Carers Australia and Carers Associations are successfully delivering information, referral advice services that broadly complement respite services to young carers. Information resources for young carers are widely used by Associations and respite services. However, the development of information resources and products has not been timely. As such, for the greater period of the Program, workers in contact with high schools have been without important resources to explain young carer issues.

A key issue for Carers Australia has been the administrative cost of distributing resources. Warehousing and distribution of information resources requires dedicated administration resources, which are not covered by the allocated funding. As a result, Carers Australia and their association members are seeking to recover distribution costs by charging services for bulk copies of the Young Carers Kit. However, this policy has not deterred CRCCs from obtaining kits, with 95% of CRCCs we surveyed using the Young Carers Kit as part of their services.

At the end of June 2007 the State and Territory Carers Associations had an estimated 1,528 individuals as registered contacts, that is, young people the Associations had provided direct support to. The young people had more than one contact with the service, so that 8,380 direct occasions of service had been provided including: 661 young people attended young carer camps or other recreational activities; 554 young people received face-to-face and telephone counselling, 413 supported referrals and 969 have been individually supported. In addition, Carers Australia and their members associations have distributed around 17,000 specific information resources to young carers and agencies.

Carers Australia report that they have had insufficient program resources to meet the demand for advice services, with counselling services being cross-funded by other programs.

Carers Associations have identified a need to raise awareness at the system or policy level with key agencies, such as education and health, and have put in place strategies with varying success at early stages. This approach is worthwhile as it validates and complements local partnerships between services and agency workers to identify and support young carers.

Outcomes for young people

Most young people and service providers (97%) agree that the program can bring a range of tangible benefits for young people: improved emotional and physical well-being; practical assistance to carry out responsibilities. Service providers also reported that the program had helped some young carers cope better at school.

One important outcome for many young people is the acknowledgment that their role has had a marked impact on their feelings of self-worth and confidence. This has assisted some young carers to better cope with and manage their responsibilities. Participation in young carer networks and conferences has also been an effective strategy in improving self-esteem and empowering young carers.

Young people particularly appreciated being able to get emotional support and independent advice and help from an adult. There was a feeling that such support helped them share the burdens of responsibility and reduced their levels of stress. Active interventions by a worker to link them with services for the care recipient or arrange other assistance reduces stress and helps young people manage their responsibilities. Where offered, information about the care recipient’s condition has also been valuable for some young people by assisting them to care for their parent or sibling.

Young people were largely satisfied with whatever level of respite or support they received from either CRCCs or Carers Associations and few identified problems with quality or unmet needs. There was a common attitude that any support was gratefully accepted, that services were generally responsive to their requests for support and that they had gained the help they needed. However, this feeling does not mean that the program has fully met the needs of young people involved or that it is meeting the broader service needs of young carers. FaHCSIA is currently funding a research study through the National Youth Affairs Scheme to identify demographic characteristics of young carers and where they are located, which will provide valuable information about the level of need for respite and support services.

Modifications to the program

The report suggests ways the program might be modified to build on its strengths and incorporate what has been learnt about how to reach young carers, what is effective respite for young carers and good practice in delivering such services. In the short term, suggested modifications include revising the Program Guidelines, broadening the definition of young carers eligible for respite and allowing services to best meet the needs of young carers on a case-by-case basis, rather than rationing direct respite in specific forms.

The report also suggests modifications that could be made to improve practice and to increase the effectiveness of awareness raising activities, information distribution and referral.

In the medium term, the program could be refocused on carer support with direct respite as one option for support.

Service models could be further developed, especially for working with young carers from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds and from Indigenous backgrounds.

Performance measurement

Although CRCCs and Carers Australia are complying with reporting requirements, the current reporting regime is not providing reliable performance information.

Key performance indicators have been reported against inconsistently and have limited relevance to how respite services are being implemented. FaHCSIA has recently developed new standardised key performance indicators for 2008-09.

Funding

Overall, program funding for respite services has been more than adequate for most metropolitan and regional CRCCs, with just seven services (17%) having to establish waiting lists.

The findings suggest that program funding for respite service should stay at the current level with increased funding to remote/ rural areas and less funding for ineffective metropolitan services. A minimum amount of funding is needed to maintain viability and for a service to access young carers effectively. New funding strategies are needed to provide sufficient staffing resources for remote and rural services to access young carers.

The evidence suggests that funding for information, advice and referrals has not been adequate to meet increasing demand arising from the success of promotion efforts. In addition, the objectives of increasing awareness of young carers in the community and providing a state-wide information, referral and advice service appear difficult to achieve for a part-time worker located in each state and territory.

Increased funding will ensure sufficient resources are available, efficient resource distribution systems are in place and counselling places are funded to meet demand. Carers Australia is seeking a substantial increase in funding annually to allow additional services to be provided, for example, a greater community development role, family centred assessment and case management options and increased brokerage of counselling. Carers Australia should develop a detailed business case to justify new funding levels.

1. Introduction

This section briefly describes the Young Carers Program, and the aims and scope of the Review.

1.1 Young carers

Caring for people with disabilities is an important feature of contemporary Australian society. One in five people in Australia report having a disability1. The Australian Bureau of Statistics defines disability as,

Any limitation, restriction or impairment which has lasted or is likely to last, for at least six months and restricts everyday activities.

The Program Guidelines define primary young carers as:

…someone up to 25 years of age who is the main provider of care and support for a parent, partner, child, relative or friend, who has a disability, is frail aged or who has a chronic mental or physical illness or alcohol/ drug dependence.

A substantial number of young people are carers in Australia, with 170,600 young carers aged up to 17 years and 348,000 young carers aged up to 25 years.2 From a population perspective, 3.6% of young people aged up to 17 years are carers and 9% of young people aged 18-25 years. Around half the primary young carers are aged up to 17 years, and 80% aged between 18-25 years are female.3

The available data reveals the profile of young carers4:

- between one-fifth and one-half live in rural or remote areas5

- young carers are usually representative of the general population in terms of cultural background

- most young carers live in NSW, Victoria and Queensland

- more than one half of primary young carers are caring for a parent, and that parent is likely to be a mother and a sole-parent household

- it is estimated that one in four young carers are providing care for a person with a mental illness.

The responsibilities of caring have been shown to limit young people’s opportunities. Young carers tend to leave school earlier than their peers, and are less likely to be in the labour force or employed. For example, in 1999 only 4% of primary young carers aged between 15-24 years were still in education, compared to 23% of other young people.6

Many carers are hidden, that is, they are unaware of available services or models of care or choose not to access government services. Young carers are often part of this group.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

1.2 The Young Carers Program

The Young Carers Program was developed as a measure for the 2004/ 2005 budget as a result of Carers Australia, The Young Carers Research Project: Final Report, DFAC, 2002. The report showed that young carers have fewer life choices and opportunities than other young people because their responsibilities impact on their ability to complete school and on their physical and mental health. The report also identified the need for policies and programs designed specifically for young carers.

As part of the Government's initiatives to support carers, the four-year $26.6 million Respite and Information Services for Young Carers Program assists young carers by supporting them to stay in education or training while continuing in their caring role. The Program targets young carers who are completing their secondary education or the vocational education equivalent and are ‘at risk’ of leaving school prematurely because of their caring role. Young Carers are defined as being at risk where because of the caring responsibilities they: frequently miss school; have no time to complete homework; feel very distracted when they are at school; experience limit connectedness with their school community and are considering leaving secondary school or the equivalent education prematurely.

The Program aims to support over 500 young carers, for each respite component, aged up to and including 25 years.

The Program has two separate but related components:

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

Respite services

The major component of the Program is provided through the national network of 55 Commonwealth Respite and Carelink Centres (CRCCs). The CRCCS are funded by FaHCSIA to deliver in-home respite through brokerage arrangements with service providers and supplementing other support programs. The 2007/ 2008 budget for the respite services is $6.9M.

Young carers can access: up to five hours at-home respite per week during school term to complete secondary education or vocational equivalent, and a two-week block of respite care a year to undertake activities such as studying for exams or training. The respite block can be used flexibly to support young carers through stressful periods associated with full-time study. The intended outcomes for young carers are improved school attendance, educational outcomes and employment skills.

The objective is to:

- help young carers better manage or balance their education and caring responsibilities. It is a targeted measure and seeks to supplement existing programs, not replace them.

CRCCs are regionally-based not-for profit organisations whose primary funding comes from the Department of Health and Ageing to deliver the National Respite Program and a range of other disability and respite programs. The CRCCs have been funded by FaHCSIA under the Young Carers Program to reflect the expected young carer population (2003 ABS Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers).

CRCCs target resources within their region of operation, with a diverse pattern of service delivery and a variety of arrangements with local service providers.

Information, referral and advice services

Carers Australia is responsible for the dissemination and development of age-appropriate information, referral and advice services to support young carers. This includes a young carers website (http://www.youngcarers.net.au) currently being re-developed and a recently launched high school education kit. State Carers Australia Associations provide advice and support services, including counselling and referrals. The objective was to develop nationally consistent information products.

The objectives are to:

- support young carers in their caring role by providing them with a clearly identifiable and accessible point of contact for information, referral and advice services

- support young carers in their caring role by providing co-ordinated and age-specific information

- provide young carers with access to timely age-specific counselling and support services

- increase awareness of young carers and their issues within the community, including but not limited to: government departments, schools and medical practitioners

- increase the rate of identification by young carers seeking assistance and support.

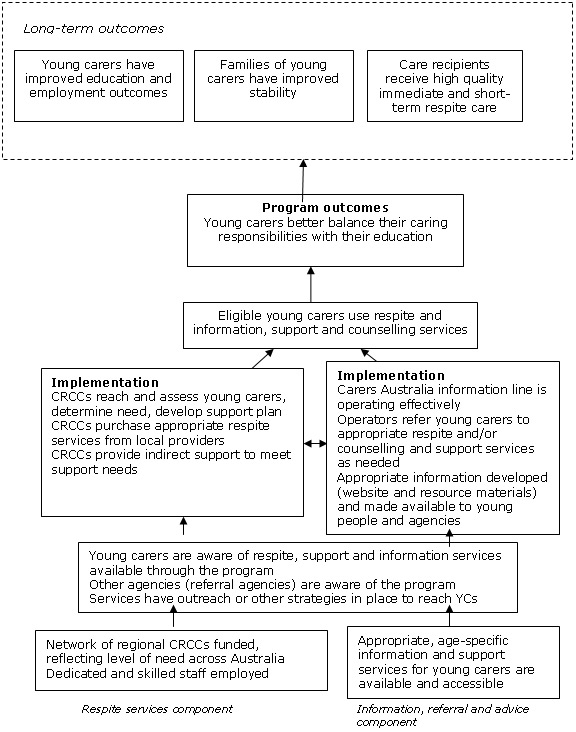

Program logic

The Program logic represents the different levels of outcomes the Program sets out to achieve, and the relationships between them (Figure 1.1). It shows how the implementation of the Program contributes to the Program outcomes and in turn to the long term outcomes for young carers, their families and care recipients.

The Program logic highlights that for young carers to utilise respite services, they need to be aware of support through the Program, and be engaged with a CRCC, while the CRCC needs to have relationships with appropriate service providers.

The Program logic shows how the two streams of the Program are intended to contribute to the Program outcomes. They function in parallel but also with the many interactions between them. For example, both CRCCs and CA may aim to reach young carers with information, depending upon the local context and the circumstances of the young carers

Figure 1.1: Program logic for Respite and Information Services for Young Carers Program

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

1.3 Scope and objectives of the Review

The purpose of the Review is to assess the effectiveness and efficiency of the Program to inform decisions about possible improvements and future directions.

The scope of the Review is the implementation of the Program since the 2004-2005 Budget provision, with a greater focus on the last year of implementation (2006-2007) and on the respite component.

Key evaluation questions

The Review aims to answer a range of key questions.

Effectiveness of implementation

The overall implementation questions are:

- What and how much has been done and how well has it been done?

- How could the Program be modified to better meet the information and respite needs of young carers?

Program outcomes

The overall results questions are:

- Does the Respite and Information Services for Young Carers Program assist young carers to better manage their education and caring responsibilities?

- Does the Program assist young carers to access suitable support and advice?

Appropriateness of funding methods

The overall funding question is:

- Is the level and method of funding adequate to ensure the Program is delivered effectively?

Adequacy of performance indicators

The overall Review question is:

- How relevant are the existing performance indicators, and what alternate indicators would better reflect the effectiveness of Program delivery?

- 1998 ABS Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers.

- ABS Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers 2003.

- Quoted in Cass, B. 2007. Youth Studies Australia, Vol 26, N0. 2 p 47.

- 1998 ABS Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carer (DAC)

- Sources differ regarding where young carers are located. The 1998 ABS Survey of DAC say one-third to one half young carers live in rural/ regional areas. The 2006 ABS Census of Population and Housing quote 19.2%

- ABS 1999.

2. Review methodology

This section provides an overview of the methods used to collect evidence for the Review.

2.1 Approach

This Review used a mixed methods approach combining qualitative case studies at ten sites, feedback from relevant stakeholders, a survey of CRCCs, analysis of documents and analysis of monitoring data from 2007/ 2008 CRCC Quarterly Reports and Carers Australia Quarterly reports from 2005 to 2008.

In all, we interviewed a total of 82 Program stakeholders from CRCCs, Carers Australia and other local providers and agencies and conducted three discussion groups at State network meetings of CRCC staff. ARTD researchers also visited eight CRCCs and two State Carers Associations.

We talked to 91 young carer clients of CRCCs and Carers Australia, through ten focus groups and 23 phone interviews.

The methodology was able to be applied effectively, but caution is needed in interpreting the results for young carers, in particular because of the positive bias introduced by sampling young people in contact with effective services or actively involved in Carers Association networks. In addition, we are missing implementation data on 24% of CRCCs.

| Data source | Method | Sample size |

|---|---|---|

| July - Sept 07 CRCC FaHCSIA Quarterly reports | Analysis of nos. YCs participating | 55 reports |

| Carers Australia Quarterly reports from 2005/ 2006 financial year to 2007 | Analysis of monitoring data (reported six-monthly) | 6 reports |

| Program stakeholders | Field visits | 8 sites, one in each State/ Territory |

| CRCCs | Written survey | 42 Response rate=76% |

| CRCC managers at case study sites | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | 8 managers |

| CRCC managers: remote and rural sites | Semi-structured telephone interviews | 5 managers |

| CRCC manager: urban site with low-level implementation | Semi-structured telephone interview | 1 manager |

| CRCC managers Qld and Vic | Discussion groups | 2 groups |

| CRCC Young Carers Program Coordinators/ CRCC workers | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | 9 workers |

| Victorian CRCC Young Carers Program Coordinators/ CRCC workers (incs one State Carers Association Young Carers Program worker) | Discussion group | 9 workers |

| Local respite service providers/ referral agencies | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews and telephone interviews | 27 workers |

| School teachers | Semi-structured telephone interviews | 8 teachers |

| Young carer clients of CRCCs | Focus groups | 8 groups and 53 YCs |

| Young carer clients of CRCCs | Semi-structured telephone interviews | 14 YCs |

| Young carer clients of Carers Australia | Focus group | 2 groups, 15 YCs |

| Young carer clients of Carers Australia | Semi-structured telephone interviews | 9 YCs |

| National DoHA officers | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | 3 staff |

| National FaHCSIA officers | Semi-structured interviews | 5 staff |

| State and Territory FaHCSIA officers | Semi-structured telephone interviews | 8 officers |

| Academics | Semi-structured telephone interviews | 2 academics |

| Carers Australia National Office Senior Executive |

Discussion group | 2 groups, 5 staff |

| Carers Associations of Qld and Vic | Discussion group | 2 groups, 10 staff |

| YC State Coordinators | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | 2 coordinators |

| YC State Coordinators | Discussion group | 1 group |

2.2 CRCC Survey

The purpose of the survey was to collect systematic independent data on the extent the respite component of the Program has been delivered and the profile of clients. The data were also intended to help fill the gaps caused by the limited nature and inconsistent reporting of monitoring data about the Program.

All 55 CRCCs were mailed a self-completed written survey including a pre-paid reply-paid envelope. Up to three rounds of reminder follow-up telephone calls were made to non-respondents.

Forty two CRCCs returned the survey; a response rate of 76%. Although we are confident that the survey results reasonably represent how the Program is being implemented for young carriers, they may introduce positive bias in terms of services provided.

The survey was piloted by two services prior to being finalised.

The survey covered:

- Information about administration of the Program (Qs 1-4)

- Information about the number and profile of Young Carers Program clients (Qs 5-8)

- Services for young carers (Qs 8-13)

- Access to respite services (Qs 14-18)

- Links with Carers Australia and use of resources (Qs 20-21)

- Promotion of service (Qs 22-25)

- Funding and Guidelines (Qs 26-27)

- Benefits of the Program (Qs 28-29).

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

2.3 Field visits to case study sites

The purpose of the field visits was to provide in-depth information on the effectiveness and efficiency of the Program in specific contexts, to complement the broader data analysis. The visits also provided an opportunity to get feedback from young people about their experiences with the Program, and explore how well these services are meeting young people’s needs and whether the Program is benefiting them.

The case study sites:

| Location | CRCC Respite services |

|---|---|

| Rural | Mid North Coast (Macksville, NSW) Australian Red Cross - South West Region (Bunbury, WA) |

| Metro | Community Based Support South (Moonah, Tas) Carers ACT (Canberra, ACT) South and East Metropolitan (SA) Northern Region (NT) |

| Regional | West Morton/ South Coast (Gold Coast, Qld) Barwon Health (Newcomb, Vic) |

Carers Australia Information and Support Services

- Carers Queensland

- Carers Victoria

Three locations that illustrate emerging findings have been written up as case studies (section 3).

During these field visits, data were collected from:

- young carers, either as part of a focus group facilitated by ARTD or through one-to-one interviews, depending on the young person’s preference. Young carers were selected at random from client lists of CRCCs and invited by letter from the CRCC to participate in the research. For one group (Victoria), the young people were selected at random from clients caring for a parent or family member with a mental illness; for a second group (NSW), the young people were selected at random from clients caring for recipients with a physical disability. All other groups had a mix of care recipients with mental and physical health issues. The invitation letter explained the reasons for the research and offered a $55 incentive payment for participating. All young carers and their parent or guardian formally consented to participating in the research. Of the 91 young people invited, 61 participated, a response rate of 67%. All groups were conducted at CRCCs (the Carers Qld and Carers Vic groups were conducted at the State Carers association offices) and many young carers were transported to the groups by CRCC workers

- CRCC service managers/ Young Carers Program coordinators and/ workers at all sites. ARTD researchers interviewed CRCC stakeholders face-to-face using semi-structured interview guides. These interviews took between 45 mins and three hours to complete

- Local respite service providers and referral agencies. ARTD researchers interviewed CRCC stakeholders face-to-face or by telephone, using semi-structured interview guides. The service providers were recommended by the CRCCs

- School welfare officers or school principals. Because of the timing of the visits in school holidays, school stakeholders were interviewed by telephone after the field visits. The informants were selected by the CRCCs on the basis of having worked with the service

- State Carers Associations – face-to-face interviews were conducted with CEOs; Program Coordinators; Young Carer Counsellor; Education Officer.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

2.4 Other qualitative data collection

The purpose of these interviews/ discussion groups was to collect information on the effectiveness of implementation of both the respite and information components of the Program, that is, the perceived impact, utility of the funding model and fit with national policy and other funding programs from key Program stakeholders.

Qualitative data were collected from a range of stakeholders:

- National Office FaHCSIA Carers Branch, Mental Health Branch and Youth – interviews conducted using semi-structured interview guide

- DoHA officers - interviews conducted using semi-structured interview guide

- FaHCSIA State and Territory officers - telephone interviews with eight officers, one from each State and Territory – interviews conducted using semi-structured interview guide

- CEOs/ Senior Managers CRCCs - discussion groups at State Program Management Meetings:

- Brisbane, 14 November 2007

- Melbourne, 22 November 2007

- Victorian Young Carers Program Coordinators - Network Meeting, 22 November 2007

- Carers Australia National Executive – discussion with the CEO, Young Carers National Coordinator, Project Manager and Business Manager. Carers Australia also provided a written submission for the Review.

- CRCC managers of three remote, three rural and one metropolitan site where Centres have experienced difficulties delivering the Program – interviews using semi-structured interview guides

- State and Territory Carers Associations Young Carer Coordinators – discussion group, 29 November 2007, Australian National Young Carers Action Team (ANYCAT) National Meeting in Melbourne

- Young Carer representatives on ANYCAT – focus group conducted during National Meeting, 29 November 2007

- Young carer clients of Queensland and Victoria State Carers Associations – mix of telephone interviews and focus groups. Carers recruited through the Associations

- Key academics - Professor Ken Pakenham, School of Psychology, University of Queensland and Dr Bettina Cass, Social Policy Research Centre, University of NSW, conducted using a semi-structured telephone guide.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

2.5 Analysis of monitoring data

CRCCs report six-monthly to the Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA) as part of the National Respite Commonwealth Program minimum data-set, and quarterly to FaHCSIA. The quarterly reporting requirement for the Young Carers Program commenced in the current financial year.

No monitoring data was available to the Review from the DoHA minimum data-set. In addition, Program-specific data for the Program is not available from the data-set, as there is no identifier used.

Over the period of the Review, only complete data for the first quarter of the 2007/ 2008 financial year was available from CRCCs. Carers Australia reports for the first and second quarters were available. Prior to the 2007/ 2008 financial year, client data were reported through DoHA Narrative Reports, and complete records of these data were unavailable. It was therefore not possible to analyse client records across the three years of the Program.

ARTD combined the records from all quarterly reports and produced a summary report by State, region and nationally. The analysis included average hours per client; average hours per occasion of service and average hours per client per week. The reporting has limitations; it does not capture the amount of indirect services accurately, and it is difficult to calculate the total number of clients because the reporting does not distinguish between ongoing and new clients.

Carers Australia quarterly reports provides summary reports of State Carers Associations’ activity levels.

The Review did not have access to quantitative data on school attendance rates for individual young carers accessing services, or long-term school retention rates or employment outcomes.

2.6 Literature scan

ARTD reviewed twelve documents to glean information about young carers support needs and models of good practice for delivering respite and carer support.

Most of the documents were provided by FaHCSIA and others were identified through key stakeholder interviews.

The documents reviewed and a summary of key information found are shown in Appendix 1.

2.7 Research

ARTD conducted limited research across State department for equivalent models of Young Carer program using literature available on websites and contacting a small number of key policy officers. The results were summarised and are documented in Appendices 1 and 2.

3. Implementation of respite component of the Program

This section assesses how well the respite component of the Program has been implemented, and presents evidence about how many and which groups of young carers have participated in the Program and where they are located. It addresses the key evaluation questions:

- How much has been done?

- What and how well has it been done?

Case studies of service delivery in three HACC locations: West Moreton South Coast Queensland; the Top-End Northern Territory; and Barwon South West, Victoria, are documented at the end of this chapter.

3.1 Participation rates

Overall, the Program has met its target of approximately 750 young carers1 being assisted a year, in 2006/ 2007 and 2007/ 2008, but not in 2005/ 2006.

Between July 2005 and February 2008, CRCCs assisted an estimated 720 to 1,200 young people each year2. The numbers of young carers being assisted has increased over time as CRCCs have developed practice models and promoted their services.

In the 2006/2007 period, half of the surveyed CRCCs assisted up to 20 young carers over the 12 month period, while a small number of services assisted 75 or more young carers. One third of CRCCs had between 0 and 10 clients.

| State | 2005/2006 | 2006/2007 | 2007/2008* | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIC | 297 | 326 | 297 | 920 |

| NSW | 191 | 319 | 333 | 843 |

| QLD | 119 | 225 | 182 | 526 |

| SA | 38 | 48 | 63 | 149 |

| WA | 21 | 47 | 64 | 132 |

| TAS | 1 | 1 | 15 | 17 |

| NT | 2 | 5 | 6 | 13 |

| All | 669 | 971 | 960 | 2600 |

Source: CRCC Survey. *July 07 to Feb 08.

CRCCS based in Victoria, NSW and Queensland have assisted the most numbers of young carers, with Victoria and Queensland showing the highest average number of young carers assisted per CRCC during 2006/07.

3.2 Characteristics of young carers being assisted

CRCCs are successfully accessing the main target group of the Program. Survey results show that most young carers receiving assistance are high school aged, that is, between 12 and 17 years of age.3 One third of the young carers are aged between 15 and 17 years, 12% are from culturally diverse backgrounds and 7% identify as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander. CRCCs report that they are increasingly being referred young carers less than 12 years of age.

| Characteristics of young carers | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Aged <12 years | 116 | 12% |

| 12–14 years | 254 | 26% |

| 15–17 years | 349 | 36% |

| 18–21 years | 119 | 12% |

| 22–25 years | 53 | 5% |

| Total | 971 | 100% |

| CALD | 120 | 12% |

| Identify as ATSI | 67 | 7% |

| Studying at vocational equivalent of school | 50 | 5% |

| Have a disability | 27 | 3% |

| Refugees | 4 | <1% |

During 2006/07, one third of young carers looked after care recipients with a mental illness and just under a quarter cared for someone with a physical disability. A significant minority of young people were also caring for family members who are chronically or terminally ill (15%) or have an intellectual disability (11%).

The proportion of young people caring for recipients with particular conditions varies somewhat between CRCCs and is influenced by the success of promotional activities and existence of referral protocols between the CRCC and agencies. For example, the Barwon Young Carers Program has close ties with a program that works with children of parents with a mental illness, and many of their referrals come from this program.

| Number of YCs assisting person with... | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Mental illnesses | 331 | 34% |

| Physical disabilities | 224 | 23% |

| Chronic or terminal Illnesses | 145 | 15% |

| Intellectual disabilities | 104 | 11% |

| Multiple disabilities or health problems | 81 | 8% |

| Dysfunction caused by severe alcohol or other drug use | 16 | 2% |

| Other (specify) | 38 | 4% |

The majority of young people were caring for a parent (61%) with a significant minority caring for a sibling (20%).

| Care recipient | No. YCs | % YCs |

|---|---|---|

| Parent | 593 | 61% |

| Sibling | 195 | 20% |

| More than one care recipient | 76 | 8% |

| Grandparent | 33 | 3% |

| Extended family | 4 | 0% |

| Friend | 0 | 0% |

3.3 Extent the Program was delivered

The Program has been inconsistently delivered by CRCCs, with some services having few if, any clients and others successfully engaging with young carers. Seven services have established waiting lists because demand exceeds capacity on occasions (section 6.1). Where the Program has been delivered effectively, CRCCs have provided more indirect respite services to best meet the respite and support needs of young carers rather than direct, in-home respite (section 5).

All of the remote CRCCs and most rural services receiving relatively small amounts of funding struggled to implement the Program and had few clients (see section 6), This is serious implementation failure given that the 1998 ABS data shows between one-third and one-half of young carers live in rural or remote areas.

There was insufficient funding to dedicate enough resources to establish the Program. Remote and rural CRCCs face other particular challenges to implementing new programs. Many have small numbers of staff working across program areas and limited ability to cover the large geographical areas covered by their service. Rural and remote CRCCs also have difficulties recruiting suitably qualified staff. Centre managers we spoke to commented that they had no or only small travel budget and no funding from the Young Carers Program to do so. Some Centres do not provide outreach; rather they work through health teams, such as aged care assessment teams to identify respite clients. Other remote services provide mobile respite services. Remote and rural CRCCs also have few other services to refer young people to, a small pool of suitable in-home respite providers and face high costs of providing respite. For example, it can cost $13,000 to transport someone from a remote area into Darwin for respite. A WA CRCC commented that the lack of family networks amongst non-Indigenous families in remote areas means that when something goes wrong the families leave the area.

Some large metropolitan and regional services that received sufficient funding to employ Program-specific workers have also failed to deliver the Program effectively. One Metro CRCC indicated that it was difficult to spend the brokerage component, as most of the services they provide are indirect. Indirect services are generally inexpensive compared to paying for direct in-home or out-of-home respite. The CRCC also stated that few agencies or key stakeholders are aware of the Program.

Another important factor influencing the extent to which the Program has been implemented is that the Guidelines are not easily applied to complex family situations (section 3.8.) For example, changeable family circumstances make it difficult to identify a primary carer and families face a range of problems. In many circumstances, other siblings (secondary carers) may also need respite and support (not allowed by the Guidelines). Some CRCCs do support secondary carers and identify one child for reporting purposes, while others do not.

3.4 Accessing young carers

Identifying young carers is a key barrier to providing respite and support for this group. Almost all (90%) of CRCCs reported that they found it difficult to identify young carers in their region, with half (49%) finding it very difficult.

| How difficult is it to identify YCs in your region? | n | % |

| Very difficult | 20 | 49% |

| Moderately difficult | 17 | 41% |

| Not difficult | 4 | 10% |

| TOTAL | 41 | 100% |

| No data | 1 |

Source: CRCC Survey, Feb 2008.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

3.4.1 Attitudinal barriers to young carers’ participation

How young carers and their families view the young person’s caring role is a barrier to young people participating in the Program. Many young people and their families simply do not initially recognise the Program as being “for them”.4

The classification ‘young carer’ is not a term readily used by families where young people have taken on a caring role. Young people do not identify themselves as “young carers”. Young carers and their families commonly regard young people taking on caring responsibilities as being a normal response to their family situation. As Bettina Cass says, ‘Care is embedded within a normative framework of obligation and responsibility’5. Identification of a young person as a primary carer appears to be even more problematic in Indigenous families, where extended families are the norm and the caring role is shared amongst the extended family members.

Young people also perceive that being classified as a carer sets them apart from their peers as being different. They have fewer opportunities to socialise and may suffer social isolation. For example, some young people report being teased or bullied about their parent’s disability. Around one third of CRCCs estimate that between 1–10% of young carers known to them refuse respite assistance. One CRCC estimated that 50% of young carers referred to their service refuse assistance.

CRCCs also report that some parents are unwilling to allow young carers to be supported under the Program.

CRCCs also indicated that some parents feel the Program has the potential to undermine their parental authority. Others are said to fear judgement by outsiders of their parenting and to have a strong desire for privacy. CRCCs also report they sometimes encounter a lack of trust in government agencies and a fear of intervention, such as the children being removed from the home. We found that some CRCCs appear to have an insufficient knowledge about their child protection responsibilities. Assessing whether a child is at risk from a child protection perspective is one area where CRCCs are seeking more clarity.

Other CRCCs say parents simply lack understanding of how the Program could benefit their child and conversely, do not recognise that their children may be disadvantaged through their caring role. Parents also sometime express the view that the family is already adequately supported by other respites services.

There is also a low awareness of difficulties faced by young carers amongst some key agencies in contact with young people. For example, the case studies highlight some teachers’ lack of awareness of problems young carers face in completing homework and attending school regularly because of their caring responsibilities. Carers Associations have strategies in place to educate key agencies and report some progress in this area but also that they have insufficient resources to make widespread changes in this area over a short time period (section 4.2.3).

3.4.2 Strategies used to promote the respite services

CRCCs generally recognise that in order to access hidden young carers, respite services must be promoted to relevant agencies likely to be in contact with young people such as schools, general respite services and health workers. The services must ‘reach-out’ to young carers as young carers are unlikely to actively seek out respite services. Using outreach strategies is a feature of an effective service model, when measured by identifying clients and successfully meeting their needs (Case studies 1 and 3). CRCCs that do not use outreach strategies effectively have fewer clients compared with other services.

CRCCs use a variety of methods for promoting their service to young carers. Most report using agency network meetings (98%), visits to service providers (81%), giving presentations to community groups (83%) and schools (81%). Three-quarters of CRCCs use brochures for promotion.

| Resource | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Agency network meetings | 41 | 98% |

| Visits to service providers | 36 | 86% |

| Community presentations | 35 | 83% |

| Visits to schools | 34 | 81% |

| YC brochure | 31 | 74% |

| CRCC forums | 29 | 69% |

| YC poster | 28 | 67% |

| Self developed brochure | 28 | 67% |

| Local newspaper | 19 | 45% |

| Other | 19 | 45% |

| Radio | 14 | 33% |

| Self developed poster | 11 | 26% |

| Self developed website | 5 | 12% |

| Carebus | 3 | 7% |

| Self developed DVD | 2 | 5% |

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

Source: CRCC Survey. Multiple responses permitted.

The most successful promotional activities are said to be agency network meetings (55% CRCCs nominated), and visits to service providers (50%). Young Carers Program workers attend interagency meetings to raise awareness of young carers and also participate in reference groups for other services. Examples of service providers targeted for visits by workers include youth pathways officers, local councils and mental health services. One CRCC in Tasmania is promoting the service via Centrelink. The CRCC has an agreement with local Centrelink Office (Carer Support Position) to send a package of young carer resources including information about the service to all young people under 25 (on their database) who are receiving a Carers Allowance or Carers Payment.

Just over a third of CRCCs nominated visits to schools (38%) as a successful promotional strategy. CRCCs have sent letters to schools, presented at staff meetings and developed posters for display in school premises, with varying levels of success. Nevertheless, just under two-thirds (64%) of CRCCs said that school staff were willing to engage with the Program on the most recent occasion they approached a school.

In South Australia, schools became more engaged in the Program when young carers’ issues were recognised at a policy level within the Education Department. One Tasmanian Centre changed their approach after being told that the schools don’t have young carers. The worker described the profile of a young carer more explicitly (late getting to school, misses school), and referrals increased. In Darwin, the young carer worker has used a range of strategies to engage school counsellors and class-based teachers (case study 2).

Interviews with CRCCs reveal that some young carer workers lack skills or knowledge of school networks/systems and find it difficult to engage schools. Others report that some teachers lack knowledge of and interest in young carers’ issues and have other more pressing student welfare priorities.

| Rating | N (CRCCs) |

N % |

|---|---|---|

| Unwilling | 3 | 8% |

| Willing | 23 | 64% |

| Very willing | 10 | 28% |

| TOTAL | 36 | 100% |

| No data | 6 |

CRCCs generally agree that in order to change attitudes towards supporting young carers amongst young carers and their families and some service agencies, it is necessary to do more to promote community awareness of young carers’ issues and available services for them. There was a common view that a national marketing campaign about the role of young carers is needed and a national brand (logo) for the Program. A Qld CRCC has developed a sample logo for the Young Carers Program. Carers Australia has developed a logo for information materials for Young Carers but CRCCs see the logo as belonging to Carers Australia and not available for general use by respite services.

The information materials developed by Carers Australia are about young carers rather than services for young carers. The lack of information about the Program itself is seen as gap. As a result, CRCCs have developed their own brochures about the respite services for young carers.

3.4.3 Referral pathways

According to CRCCs, young carers hear about the service mainly through their teachers or other school staff, through friends or family, or through disability, youth and other health services. Some families are already involved with other programs under the CRCC, which has resulted in referrals to the Young Carers Program. In remote services, it is common for a referral to come through a CRCC because the family is known to the service. One CRCC in Tasmania is using Centrelink as a referral agency and a Victorian CRCC both makes and receives referrals from a project funded under the Children of Parents with Mental Illness Program.

The young people confirmed the evidence from CRCCs, finding out about the Program through school counsellors, parents, via another respite service and hospital social workers. Few contacted a CRCC service directly, with an adult generally doing so on their behalf. Young carers were motivated to consent to support because they wanted help for themselves or the person they care for and because the social activities appealed to them (section 5).

Interviews and discussion groups revealed that referrals tend to be informal, either by phone or email, if a service is unclear about the appropriateness of a referral they will speak to the Young Carers Program worker directly. One Queensland CRCC has formal processes in place to ensure referrals are appropriate and that referral agencies understand who is eligible for the service. Without formal processes there is a risk referrals will not be made. For example, one community stakeholder we spoke to knew about the Program but did not have details about who and how to make referrals and, as a consequence, had not made any referrals.

Response |

N CRCCs |

% CRCCs |

|---|---|---|

| Teachers or other school staff | 18 | 43% |

| Friends or family | 18 | 43% |

| Disability services | 16 | 38% |

| Youth services | 15 | 36% |

| Other health services | 15 | 36% |

| CRCC advertising | 13 | 31% |

| CA State office staff | 11 | 26% |

| Other | 10 | 24% |

| CA local branch staff | 6 | 14% |

| Mental health providers | 6 | 14% |

| Centrelink | 6 | 14% |

| CA website | 5 | 12% |

| CA brochures eg YC kit | 2 | 5% |

| Drug and alcohol services | 2 | 5% |

Source: CRCC Survey, Feb 2008. Multiple responses permitted.

CRCCs stated that referrals are increasingly complex as the Program gets better known by “first-to-know” agencies.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

3.5 Service delivery

A detailed description of how the respite services are being delivered in three separate locations can be found at the end of this section in the case studies. This section provides an overview of how respite services are being implemented.

3.5.1 Operation

The way the service is delivered reflects the amount of funding CRCCs are given to implement the Program. The service may be delivered by a dedicated worker/s with support from other staff from time to time or become part of a generalist respite worker’s duties, depending on available funding.

The number of full-time equivalent (FTE) staff designated to work with young carers ranges from none to 2.5 FTEs, with 43% of services operating with one FTE staff member or less.

The survey results show that 58% of CRCCs have one staff member working directly on the Young Carers Program, a third of CRCCs have two staff and a small number have three staff. A quarter of CRCCs have two staff members working indirectly on the Program, while a third of CRCCs have four or more staff working indirectly on the Program.

Just over half of CRCCs (58%) report that they require staff who are working directly with young carers to have formal qualifications, ranging from certificates to degrees, and sometimes stipulating the area of qualification, for example, welfare, social science, youth work, education.

There is also a broad range of ways brokerage funding is being used from brokering direct respite support to brokering organisations that provide skills-based camps or tutoring. For example, it is not uncommon for CRCCs to broker out tutoring and domestic assistance. One service in Tasmania brokers all services both indirect and direct through 43 partnerships with other services. Services also broker out direct respite with a substitute carer coming into the home to provide time to complete homework or out-of-home care.

Figure 3.1: Example of case management approach

A CRCC cited a case where two young carers were missing a lot of school because they were caring for a parent with motor neurone disease. The children were sole carers and there was minimal involvement from HACC. The CRCC worker organised 24 hours of respite; arranged for the older child to combine distance education with going to local school; sent both children to a camp; liaised with other support agencies and helped coordinate these and linked the children with the school welfare officer.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

3.5.2 Types of services provided

CRCCs offer a wide range of services including a mix of indirect and direct respite services, with indirect services being more commonly provided than direct respite services. The mix of services has evolved over time and been driven by the expressed needs of young carers and by what is age appropriate and fits their family situation. Young carers have demanded indirect rather than direct respite services seeing these kinds of services as giving them respite from their caring roles (see 3.5.4 and section 5). CRCCs also differ in approaches used and mix of services offered.

Where cases are complex, some services are using a case management approach and developing care plans for the young person. Workers meet with the young person and their family and assist young people to coordinate services for themselves and the care recipient6, negotiate with school, refer young people to other services including counselling and Centrelink, assist young people to manage household responsibilities, and link the care recipient in with services if appropriate. CRCCs indicated that many young people need intensive support and/ or a long period of support, and that it can take some time to engage the young person and their family and engender trust.

Over 80% of CRCCs provide domestic assistance (house cleaning and cooking meals), and more than half (60%) reported that this was the most frequently accessed support. A similarly high proportion of CRCCs offer assistance with referrals to other programs for ongoing support. Two-thirds of CRCCs report providing transport, home visits and tutoring for young carers.

A majority of services provide phone call check-ins (emotional support), activities during school holidays, social support and material assistance. Just over half offer Young Carer Camps. Examples of the kinds of social activities and material assistance provided are camps; movie tickets/ vouchers; payment of fees to join sporting clubs; purchase of school uniforms and books; payment of school fees and driving lessons.

Along with domestic assistance, the most frequently accessed supports for young carers are tutoring (48%) and social support, such as social groups (29%). Around one fifth of CRCCs report young carers frequently access transport services.

| Response category | N CRCCs |

% CRCCs |

|---|---|---|

| Domestic assistance | 35 | 83% |

| Assistance with referrals to other programs for ongoing support | 33 | 79% |

| Transport | 29 | 69% |

| Home visits | 29 | 69% |

| Tutoring | 28 | 67% |

| Phone calls/ check-ins | 27 | 64% |

| Activity days during school holidays | 27 | 64% |

| Social support (e.g. sports groups) | 25 | 60% |

| Material support (e.g. school books; school uniforms; gym fees) | 25 | 60% |

| Young Carers Camps | 22 | 52% |

| 24-hour blocks of respite at assignment or exam times | 21 | 50% |

| Peer support with other young carers | 21 | 50% |

| Counselling | 21 | 50% |

| Skills development (e.g. cooking; budgeting; stress management) | 20 | 48% |

| Week blocks of respite for recreation, family holidays, camps | 20 | 48% |

| Case management | 20 | 48% |

| Other* | 16 | 38% |

| Mentoring | 13 | 31% |

Notes: Multiple responses permitted. * Other services offered to young carers include anger management, financial advice, driving lessons, vouchers for respite options, Family Day Care, Centrelink support, medical alarms, home and garden maintenance, shopping.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

3.5.3 Use of and appropriateness of respite packages

The Program offers two kinds of direct respite packages: blocks of respite which may be provided as 24 hours, one-week or two-week blocks or five hours respite per week during school term. Although young people use direct in-home or out-of-home respite less frequently than other services and these services are not always appropriate, they do provide valuable assistance in specific circumstances.

Young people were said to prefer using the five hour respite as tutoring or domestic assistance rather than as in-home care, where a temporary alternate carer looks after the care recipient. Examples of ways direct in-home respite is used are to provide non-nursing support so that young people can attend after school activities, attend tutoring at school or another location or go to the movies. In-home support may also have the desired outcomes of providing companionship for the care recipient.

Block respite is rarely used as a two-week block, with the preferred use as 24-hour blocks. Just four CRCCs indicated they had used two-week blocks of respite. CRCCs commonly said that young people did not request the two-week blocks and they were unable to use this and regard this kind of respite package as being inappropriate for young people, given their family situations and age. CRCCs indicated young carers more often need shorter and more frequent assistance. Fewer than 10% of CRCCs indicated that direct respite in the form of 24-hour blocks is used frequently. An example of the use of 24-hour block funding is having an adult stay overnight as an alternate carer when a care recipient has been recently discharged from hospital.

There was a common view that allocating and rationing direct respite under one of two ways of delivery inhibits services’ ability to be flexible and meet carers’ needs. Although half of the survey respondents agreed that five hours respite per week during school terms was sufficient to meet the needs of young carers, only one third agreed that two-week blocks of respite are sufficient.

Direct in-home respite is not always appropriate because young people prefer respite as time out in recreation or to socialise, and some are reluctant to trust other people to care for their family member, particularly when substance abuse or mental illness is involved. CRCCs also report that some parents see direct respite as an insult to their parenting skills or fear others might question their parenting abilities and are unwilling to have ‘strangers’ in their home. In addition, respite packages are designed around school terms and respite needs are year round.

| Block respite | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| One two-week block | 0 | 0% |

| Two one-week blocks | 4 | 11% |

| 24-hour blocks | 19 | 50% |

| Flexible as needed | 8 | 21% |

| No requests | 7 | 18% |

| TOTAL | 38 | 100% |

| No data | 4 |

Source: CRCC Survey, Feb 2008.

3.5.4 Links with other government services for young carers

Case studies reveal that many CRCCs work with other government agencies to provide support to young people. Workers may simply share information during meetings and/ or make cross-referrals and/ or coordinate support for the young person. Links may be through formal partnerships or informal relationships at the worker level, depending on the service model used by the CRCC. Examples of collaborative partnerships were found with mental health services, Centrelink, youth services, schools.

Developing links with other services is an important strategy in planning for ongoing support for the young carer. Particularly with the increasing complexity of referrals as the Program becomes better known. CRCCs commonly observed that more young people are presenting with complex family situations.

However, CRCCs report that finding alternate support for young people can be very challenging, particularly if there are insufficient resources to employ dedicated workers to develop those links. In rural and remote areas CRCCs may have an additional difficulty, with few suitable youth specific or culturally appropriate services to refer young people to. Other CRCCs report they face difficulties finding suitable counsellors to refer young people to and, in particular, a lack of youth-specific counsellors and/ or male counsellors. A common challenge in getting ongoing support from other agencies is that these that tend to be one-issue focused.

Another common challenge is that it can be difficult to obtain HACC services for young people who are not recognised as being eligible for HACC services. Young people value domestic support via the Program and CRCCs are frustrated that it is difficult to refer young carers to get ongoing domestic support. On the other hand, some CRCCs report that HACC may already be supporting the families of the young carers.

The National Respite Program (NRP) encompasses young carers, but in reality there is fairly limited funding for young carers under that Program. The main targets are carers of the frail aged and to a lesser extent carers of those with disabilities. The Department of Health and Ageing Guidelines state that when considering priority for services for young carers, CRCCs should consider whether the young carers are eligible for FaHCSIA funding – this may mean that young carers outside the definition could miss out on services.

Links with Carers Association’s information and counselling services are discussed in section 4.4.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

3.6 Compliance with and appropriateness of Guidelines

Although CRCCs have endeavoured to comply with the original Guidelines, it is apparent that there are occasions when CRCCs have interpreted the Guidelines differently in order to be flexible and meet the respite needs of young carers. In fact, 84% of CRCCs who responded to the survey agreed that the Guidelines need to be modified. They commented that the original Program Guidelines are not always relevant or applicable to complex and changing family situations.

In mid-2007, FaHCSIA informed the CRCCs that the Guidelines were to be interpreted more flexibly so that young carers included 25 year olds and young carers in primary education could be assisted through the Program, assessed on a case-by-case basis, and that an extension of the 12-month limit could be considered, if needs were high. CRCCs strongly supported this approach.

CRCCs are providing services to young carers at primary school struggling to keep up with schooling because of their caring responsibilities, under the rationale that in the long term, they are at increased risk of leaving school early (12% of all cases). CRCCs reveal that in some instances young carers are without any other supports.

Case studies reveal that CRCCs are supporting some young people for longer than the 12-month limit, where required. Most CRCCs disagree with a 12 month limit, commenting that limiting respite for young carers is inappropriate because it fails to recognise the often on-going nature of the caring role and concomitant ongoing need for respite services and the lack of alternate sources of respite.

CRCCs are also providing services to 17% of young carers aged 18–25 years stating that some young carers in tertiary education need respite and lack alternate sources of support. Given the stated lack of alternate support available and the apparent need there is a case for including this group in the program.

STOs and CRCCs also report that, ‘the main provider of care definition is being applied quite broadly in some areas and narrowly in others.’ As a consequence, it appears most CRCCs are, on occasions, taking on client referrals for secondary or alternate carers who they consider may also be at risk of leaving school early. Some young carers although not the main carer, also take on significant caring responsibilities.

Stakeholders (CRCCs and Carers Australia) argue that the scope of the Program should be broadened so that it can prevent and ameliorate mental and physical health problems arising from their caring responsibilities and not narrowly focus on school retention. The Program also misses out young carers who have already left school and are not pursing vocational education.

3.7 Elements of effective practice

The evaluation and the brief review of literature have revealed key elements necessary to engage young carers and meet their respite needs.

These elements are:

Choice: offer a range of services, both indirect and direct and allow young carers to choose activities and services that will best meet their respite and support needs. The issues faced by young carers may be complex or simple, as young carers have variable family situations and caring roles. As one young person commented, ‘Organisations should realise that every carer is different because the people they care for don’t have the same thing’. Available services could include: recreational opportunities; personal support (informal and formal counselling); domestic assistance; tutoring; and in-home respite.

Outreach and networking with key ‘first-to-know’ referral agencies: it is necessary to work with key referral agencies including schools, health services and disability services to access young carers. Young carers commonly do to not think of themselves as carers, nor do they know where to go to for extra support and rarely actively seek help.

Establish formal referral and intake procedures: to ensure that referral pathways work efficiently and effectively and so that referral agencies are assured young people are being supported as needed.

Use a case management approach [case planning]: to identify young carers’ needs and ensure that appropriate services are provided and on-going support needs are identified and strategies in place to provide these.

Take a whole family approach: consult with the young person’s family when planning respite services and assist the carer and other siblings where possible. Engagement of parent/s and family is important in meeting young person’s needs.

Offer intensive personal support (where needed): young people value independent advice and emotional support highly and such support assists young people to manage their caring responsibilities (respite effect).

3.8 Conclusions

Implementation of the respite services has been characterised by diverse approaches and levels of commitment, driven by the poor fit between the service model framed in the Guidelines and the expressed respite needs of young people. CRCCs have faced difficulties accessing hidden young carers and sometimes working with this unfamiliar client group. Service delivery has evolved over time to include outreach strategies and a focus on indirect services, rather than direct services, although there remains a place for these. Flexibility in service delivery is a key principle in providing effective respite services for young people.

The original Guidelines were based on a traditional concept of respite, where a respite effect would be achieved when the caring role is formally provided by others on a temporary basis. In practice, direct respite was only occasionally suitable for young people and other services proved to be both more acceptable to young people and to offer a respite effect. A service model, based on using a case management approach and taking into account the family situation is evolving and we recommend that key elements of effective practice – outreach, case management, a family approach, formal collaboration with key referral agencies be incorporated into all CRCC’s service delivery. We also recommend that the Guidelines be broadened to allow young people to be supported for more than 12-months and that the definition of “Young Carer” include alternate, part-time main carer or secondary carers as well young carers at primary school and in tertiary education. FaHCSIA should also consider removing the “rationing” of direct respite services to provide further flexibility in service delivery.

A majority of young carers using respite services have significant caring responsibilities, caring for a parent with mental illness or a chronic illness or disability. Many face complex family situations. As such, the Program needs to build on and encourage partnerships with support agencies. For example, stronger links might be developed with the program for Children of Parents with Mental Illnessand mental health services at the local service level. Workers may need specific training about mental health issues. Health professionals, in contact with people with mental illnesses and chronic conditions, such as General Practitioners, nurses and social workers will be important sources of referrals.

Another key partner agency is the education sector. Although CRCC workers and Carers Australia are actively promoting young carer issues to schools, the evidence shows there remains substantial work to be done to get the welfare of young carers recognised more broadly amongst school teachers and counsellors. The development of information materials such as the Young Carers Kits is one strategy. However, experience in the health promotion field shows that a broader range of approaches are needed to get new health and welfare issues addressed in schools. One of these lessons is that schools are focused on educational outcomes and it is necessary to demonstrate how the student welfare affects education or links with the syllabus. The evidence is clear that the welfare of young carers does affect educational outcomes. Systems based approaches at the departmental level to direct school welfare policy at the local level are necessary to bring about broad-based change. In the health promotion field, studies have shown that bringing about changes in policy needs a long view and to involve the sector as active partners in the process. At the local level, professional development is important, as is working closely with key school staff members.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

Case Study 1: Gold Coast

Context

This Young Carers Program is located in a coastal tourist region, the Gold Coast in Queensland. The community serviced by the Program is fairly transient, and many people move to the area with no family support. The area has only a small number of Indigenous people and people from CALD backgrounds.

The young carers we talked with in this case study area reported that they perform a variety of support functions, including: practical help, such as housework, shopping and cooking; looking after younger siblings; taking care of medications; and organising hospital and doctor’s appointments. Young carers reported mixed experiences with dealing with school as young carers:

‘I was in trouble with teachers as I never got my homework in.’

‘I had teachers saying that just because your mum is going to die is no reason not to do work. I would get expelled from school because I’d get into fights with teachers’.

‘All my teachers were really nice about it, as soon as my mum was in hospital teachers knew and were really supportive, [they] said I didn’t have to go to school if I didn’t want to.’

‘If I missed school they would sit down with me the next day and help me do the schoolwork.’

Young carers