Australian Government Disability Services Census Report 2008

The Disability Services Census Report 2008 provides detailed information on Australian Government funded specialist disability services and their consumers.

Table of contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter One: Executive Summary

- 1.1 Background

- 1.2 Outline of the Report

- 1.3 Main counts and definitions

- 1.4 Summary of main findings

- 1.5 Data summary of all disability service outlets, 2007-08

- 1.5a Data summary of disability employment services, 2007-08

- 1.5b Data summary of open employment services, 2007-08

- 1.5c Data summary of supported employment services, 2007-08

- 1.5d Data summary of advocacy services, 2007-08

- 1.5e Data summary of respite services, 2007-08

- 1.5f Data summary of print disability services, 2007-08

- 1.5g Data summary of information services, 2007-08

- Chapter Two: History of the Disability Services Census

- Chapter Three: Disability service outlet profile

- Chapter Four: National disability employment services consumer profile

- Chapter Five: Trend series—Disability employment service consumers

- Chapter Six: State and territory summary statistics

- Chapter Seven: Appendices

- Chapter Eight: Glossary of Terms

- References

List of Tables

- Table 3.1: State distribution of disability service outlets across Australia, 2007-08

- Table 3.2: Number of disability service outlet types in each state, 2007-08

- Table 3.3: Percentage of disability service outlet types in each state, 2007-08

- Table 3.4: Number of disability service outlet types, by geographic location, 2007-08

- Table 3.5: Disability service outlet type, by number of hours operating per day, 2007-08

- Table 3.6: Disability service outlets, by number of operating days per week, 2007-08

- Table 3.7: Disability service outlet type, by number of operating days per week, 2007-08

- Table 3.8: Disability service outlet type, by operating weeks in 2007-08

- Table 3.9: Disability service outlet type, by FTE direct and indirect support paid staff, 2007-08

- Table 3.10: Disability service outlet type, by FTE volunteers in a typical week, 2007-08

- Table 4.1: All disability employment service consumers, by main reason for leaving the disability employment service, 2007-08

- Table 4.2: All disability employment service consumers, by most common overseas country of birth, 2007-08

- Table 4.3: All disability employment service consumers, by accommodation setting, 2007-08

- Table 4.4: All disability employment service consumers, by level of support needed in each main life area, 2007-08

- Table 4.5: All disability employment service consumers, by level of support needed in each main life area, 2006-07 & 2007-08 comparison

- Table 4.6: All disability employment service consumers, by primary disability type and employment outcome, 2007-08

- Table 4.7: All open employment service consumers, by main reason for leaving the open employment service, 2007-08

- Table 4.8: All open employment service consumers, by most common overseas country of birth, 2007-08

- Table 4.9: All open employment service consumers, by geographic location of usual residence, 2007-08

- Table 4.10: All open employment service consumers, by accommodation setting, 2007-08

- Table 4.11: All open employment service consumers, by level of support needed in each main life area, 2007-08

- Table 4.12: All open employment service consumers, by primary disability type and employment outcome, 2007-08

- Table 4.13: All supported employment service consumers, by main reason for leaving the supported employment service, 2007-08

- Table 4.14: All supported employment service consumers, by location of birth category, 2007-08

- Table 4.15: All supported employment service consumers, by most common overseas country of birth, 2007-08

- Table 4.16: All supported employment service consumers, by geographic location of usual residence, 2007-08

- Table 4.17: All supported employment service consumers, by living arrangements, 2007-08

- Table 4.18: All supported employment service consumers, by accommodation setting, 2007-08

- Table 4.19: All supported employment service consumers, by level of support needed in each main life area, 2007-08

- Table 4.20: Supported employment service consumers ‘on the books’, by employment phase, 30 June 2008

- Table 4.21: Supported employment service consumers ‘on the books’, by basis of employment, 30 June 2008

- Table 4.22: Supported employment service consumers ‘on the books’, by full-time/part-time status and average hours worked per week and primary disability type, 30 June 2008

- Table 4.23: Supported employment service consumers ‘on the books’, by full-time/part-time status and average hours worked per week and state, 30 June 2008

- Table 4.24: Supported employment service consumers ‘on the books’, by gross weekly wage and primary disability type, 30 June 2008

- Table 4.25: Supported employment service consumers ‘on the books’, by gross hourly wage rate and primary disability type, 30 June 2008

- Table 4.26: Supported employment service consumers ‘on the books’, by method used to set pay, 30 June 2008

- Table 5.1: Change in disability employment services consumer population, by employment service type, 2000-01 to 2007-08

- Table 5.2: Change in the female disability employment services consumer population, by employment service type, 2000-01 to 2007-08

- Table 5.3: Change in the Indigenous disability employment services consumer population, by employment service type, 2000-01 to 2007-08

- Table 5.4: Change in the non-English speaking background disability employment services consumer population, by employment service type, 2000-01 to 2007-08

- Table 5.5: Change in the disability employment services consumer population, by primary disability type, 2000-01 to 2007-08

- Table 5.6: Change in the open employment services consumer population, by primary disability type, 2000-01 to 2007-08

- Table 5.7: Change in the supported employment services population, by primary disability type, 2000-01 to 2007-08

- Table 1A: Total staff hours in the reference week, by disability service outlet type and state, 2007-08

- Table 2A: All consumers: employment service type by age range, 2007-08

- Table 3A: All consumers: employment service type, by gender and state, 2007-08

- Table 4A: All consumers: Indigenous status, by state and employment service type, 2007-08

- Table 5A: All consumers: country of birth, by state and employment service type, 2007-08

- Table 6A: All supported employment consumers: main language spoken at home, by state, 2007-08

- Table 7A: All consumers: need for interpreter assistance, by state and employment service type, 2007-08

- Table 8A: All consumers: other significant disability, by primary disability and employment service type, 2007-08

- Table 9A: All consumers: need for assistance, by primary disability and main life area, 2007-08

- Table 10A: All consumers: need for assistance by employment service type and main life area, 2007-08

- Table 11A: All supported employment consumers: basis of employment by state, 30 June 2008

- Table 12A: Employed consumers: weekly wage, by employment service type and census year (2008, 2007, 2006, 2005, 2004, 2003)

List of Figures

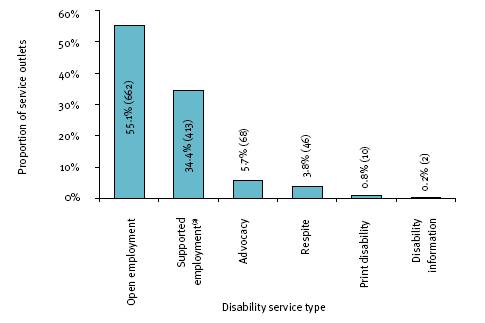

- Figure 3.1: Disability service outlets, by service type, 2007-08

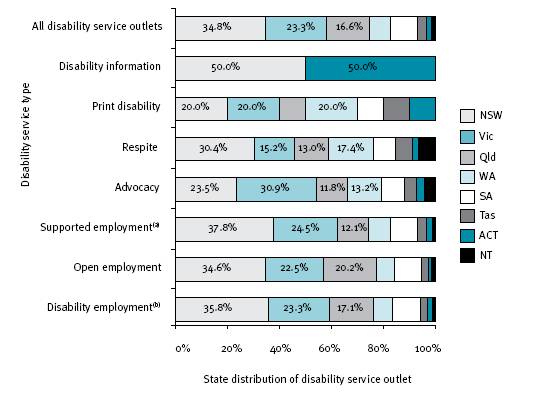

- Figure 3.2: State distribution of disability service outlet types across Australia, 2007-08

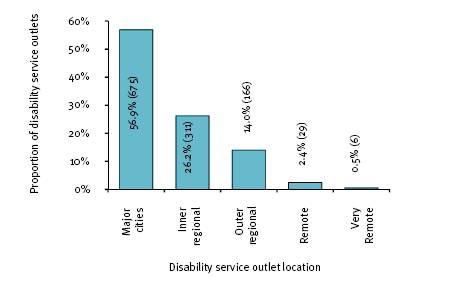

- Figure 3.3: Disability service outlets, by geographic location, 2007-08

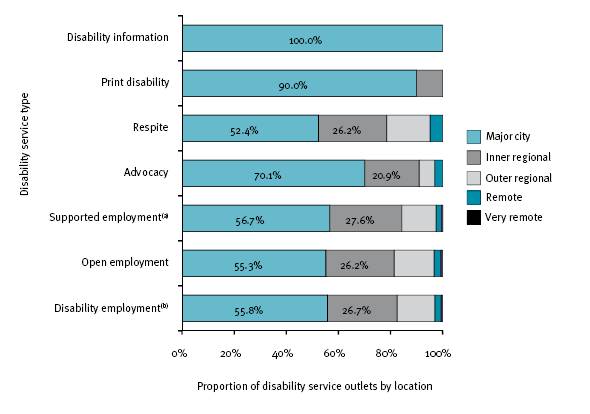

- Figure 3.4: Percentage of disability service type outlet, by geographic location, 2007-08

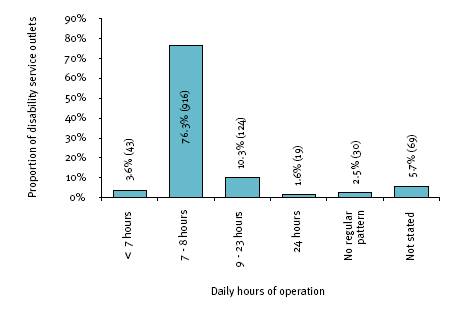

- Figure 3.5: Disability service outlets, by number of hours operating per day, 2007-08

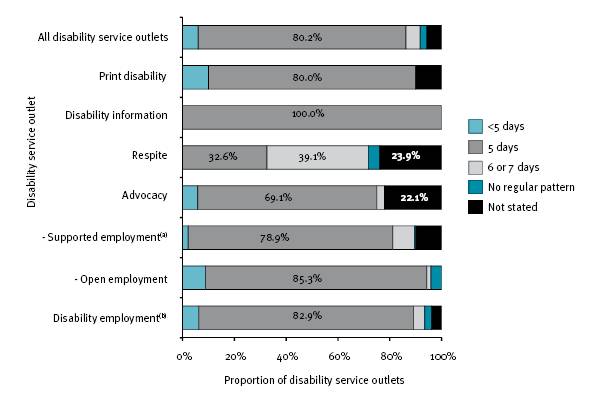

- Figure 3.6: Disability service outlet type, by operating days per week, 2007-08

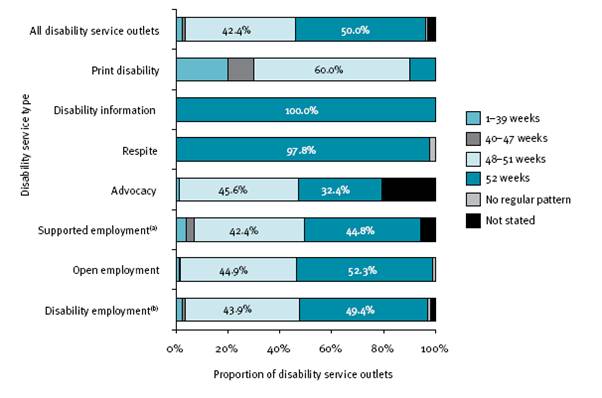

- Figure 3.7: Disability service outlet type, by operating weeks in 2007-08

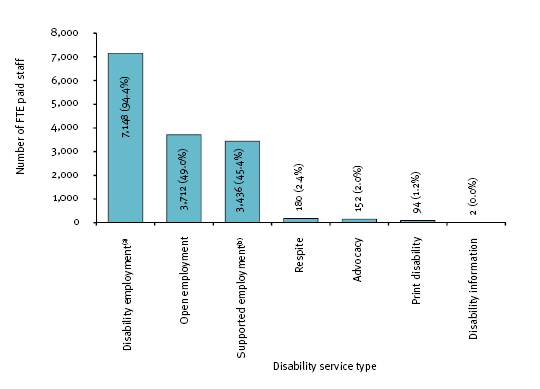

- Figure 3.8: Disability service outlet type, by FTE paid staff, 2007-08

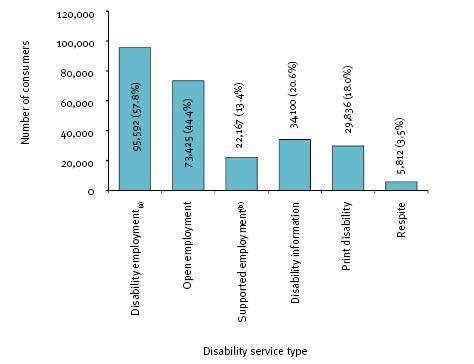

- Figure 3.9: All consumers assisted, by disability service outlet type, 2007-08

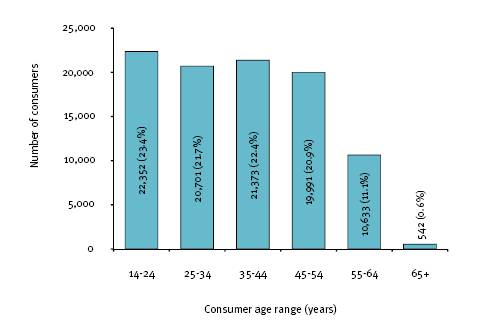

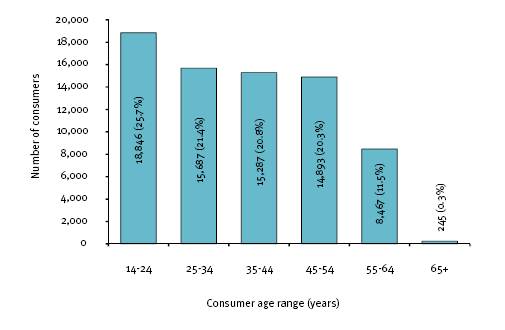

- Figure 4.1: All disability employment service consumers, by age group, 2007-08

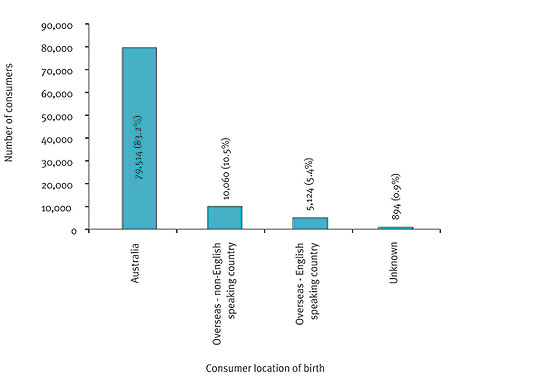

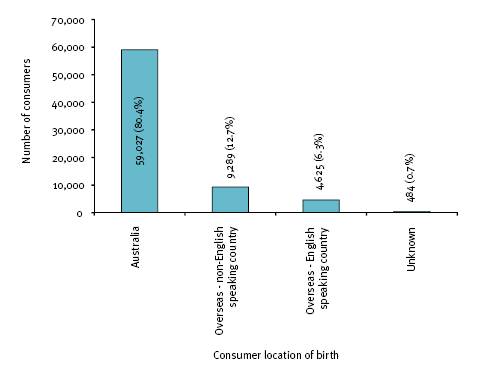

- Figure 4.2: All disability employment service consumers, by country of birth category, 2007-08

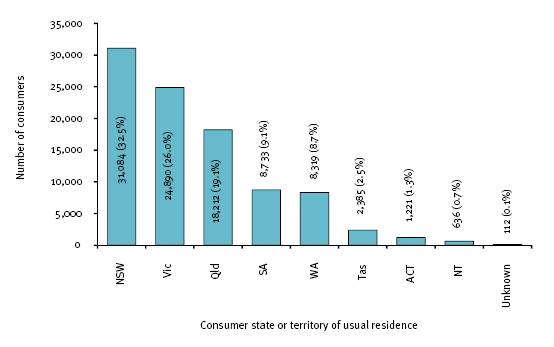

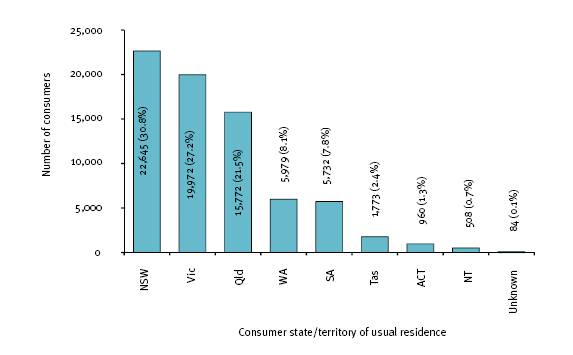

- Figure 4.3: All disability employment service consumers, by state or territory of usual residence, 2007-08

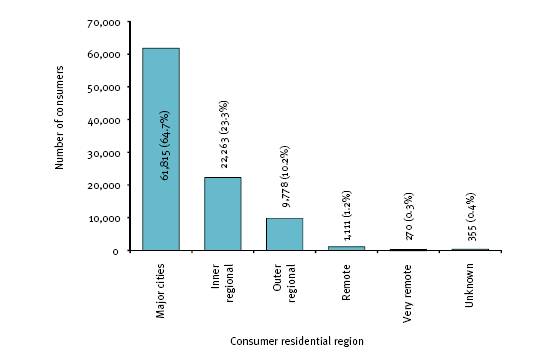

- Figure 4.4: All disability employment service consumers, by geographic location of usual residence, 2007-08

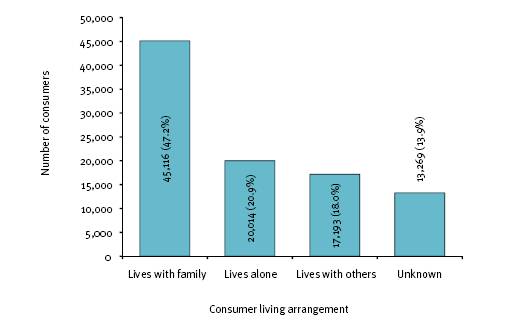

- Figure 4.5: All disability employment service consumers, by living arrangements, 2007-08

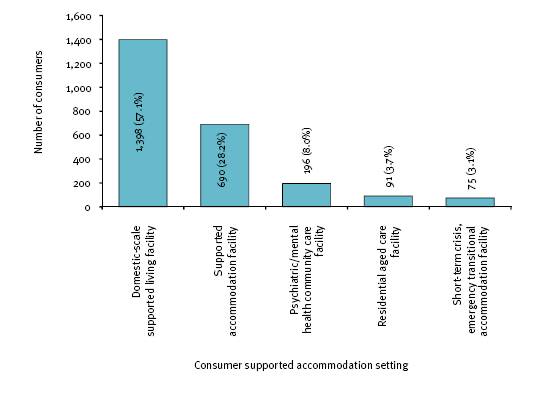

- Figure 4.6: All disability employment service consumers that are in supported accommodation, by supported accommodation setting, 2007-08

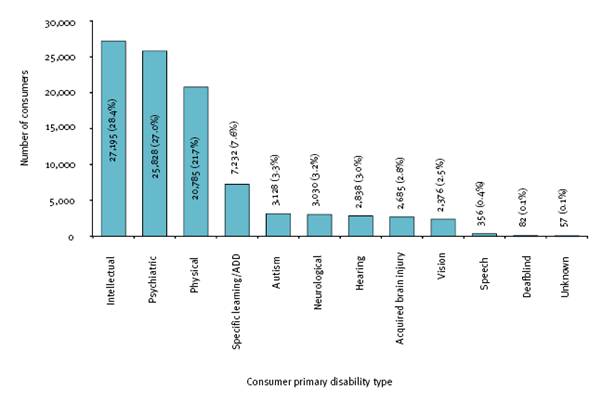

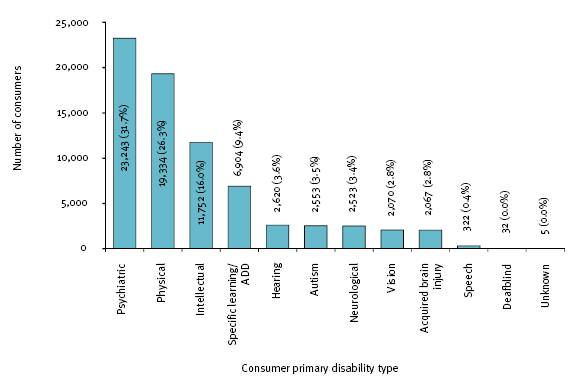

- Figure 4.7: All disability employment service consumers, by primary disability type, 2007-08

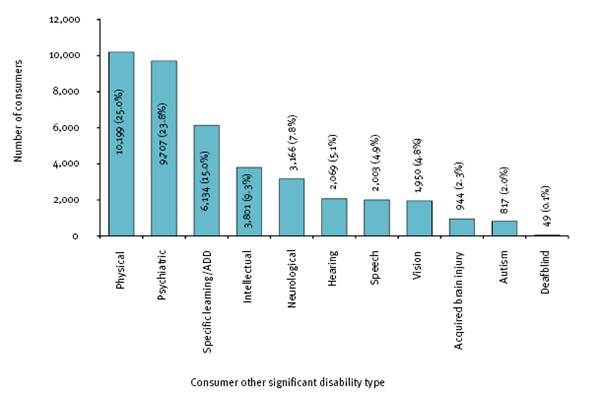

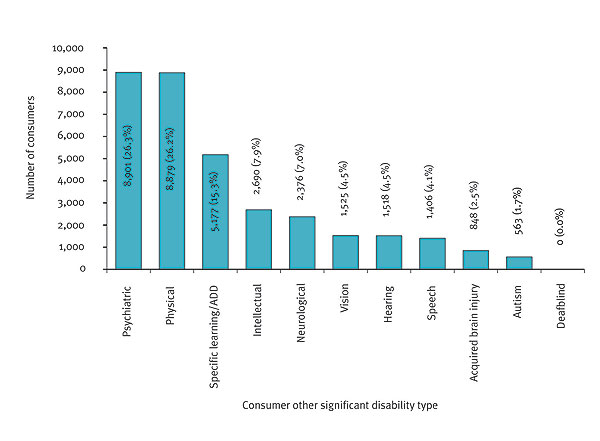

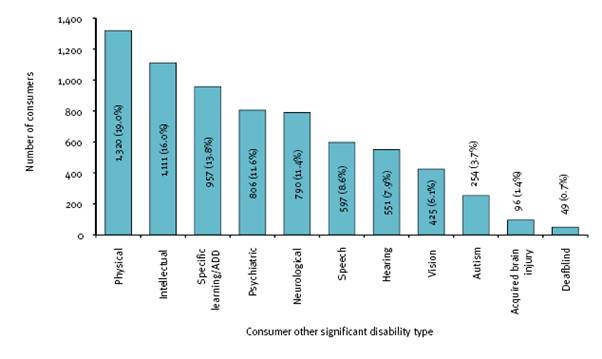

- Figure 4.8: All disability employment service consumers with another significant disability, by other significant disability type, 2007-08

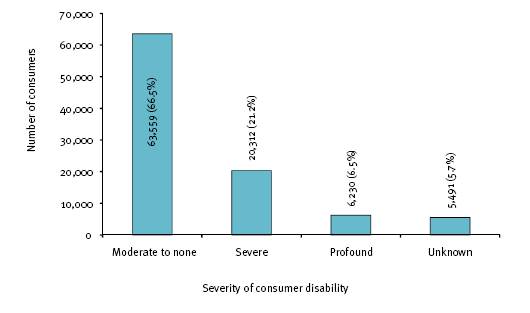

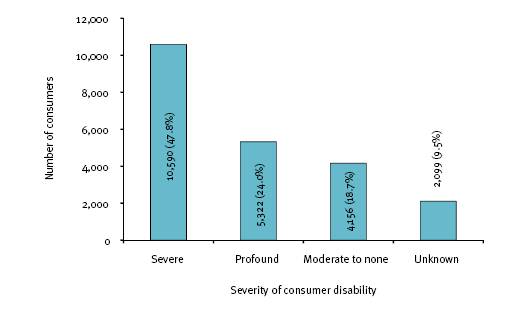

- Figure 4.9: All disability employment service consumers, by severity of disability, 2007-08

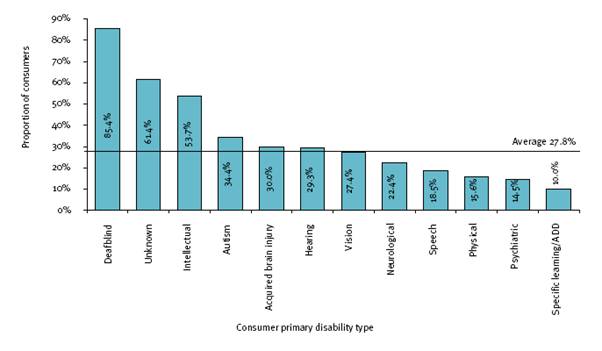

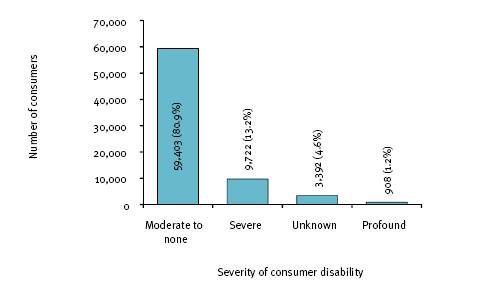

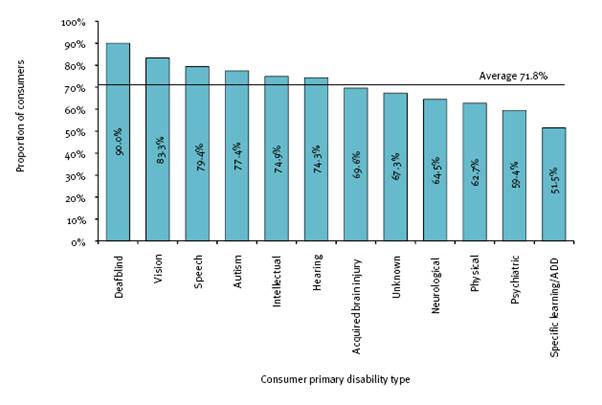

- Figure 4.10: All disability employment service consumers with a profound or severe core activity limitation, by primary disability type, 2007-08

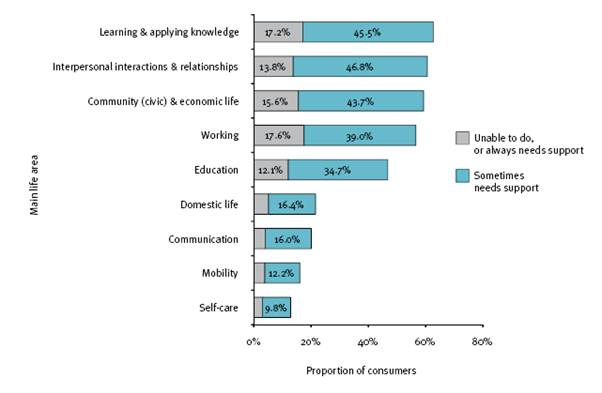

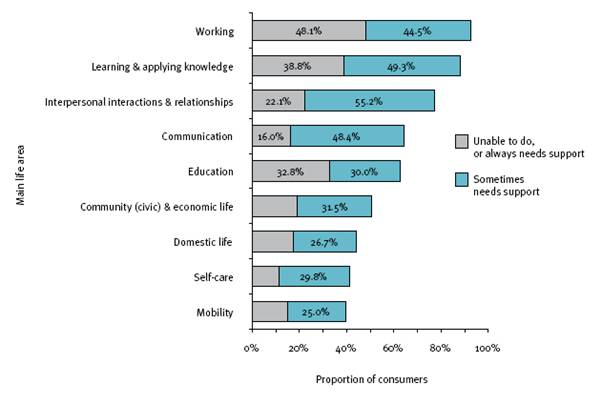

- Figure 4.11: All disability employment service consumers who always or sometimes needed support, by main life area, 2007-08

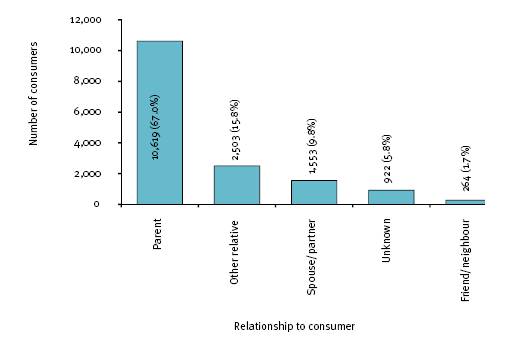

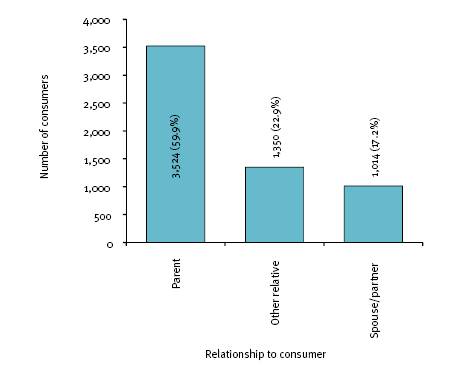

- Figure 4.12: All disability employment service consumers, by relationship of informal carer to consumer, 2007-08

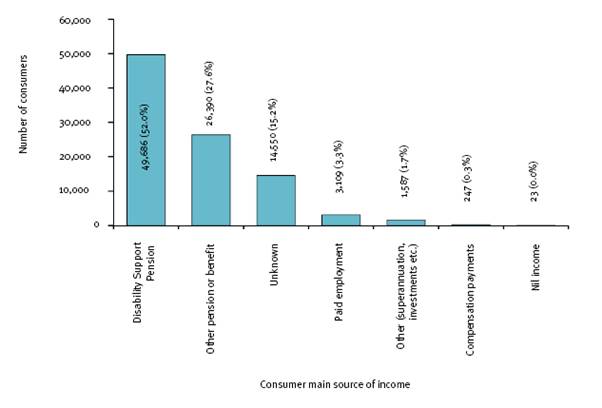

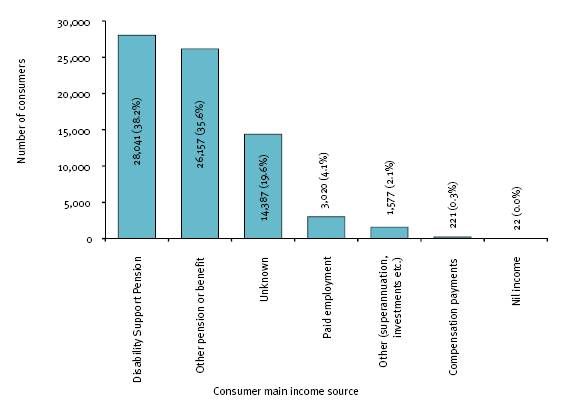

- Figure 4.13: All disability employment service consumers, by main source of income, 2007-08

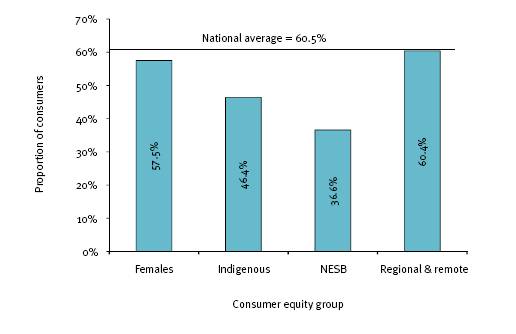

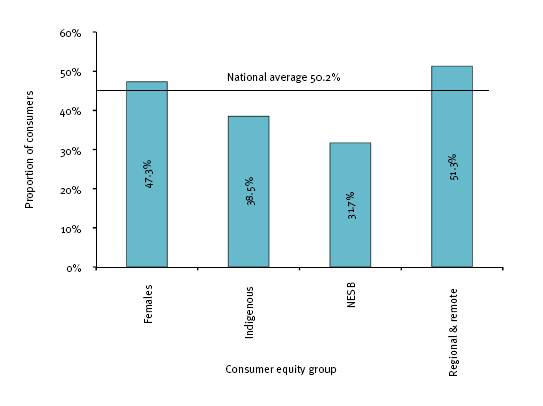

- Figure 4.14: All disability employment service consumers, by equity group and employment outcome, 2007-08

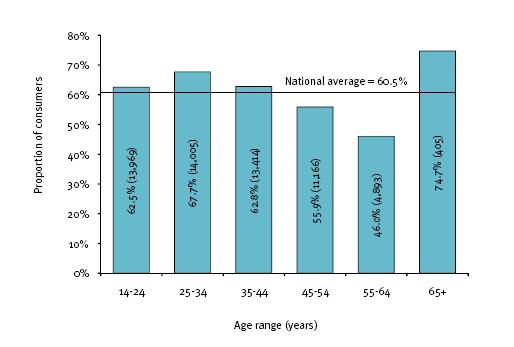

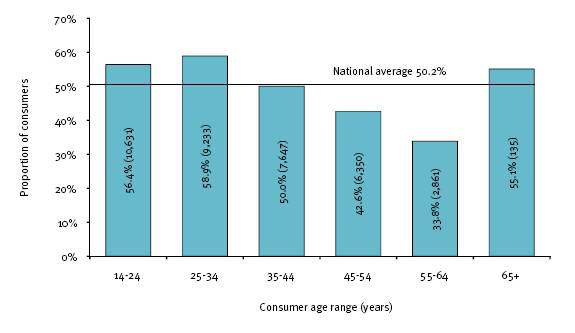

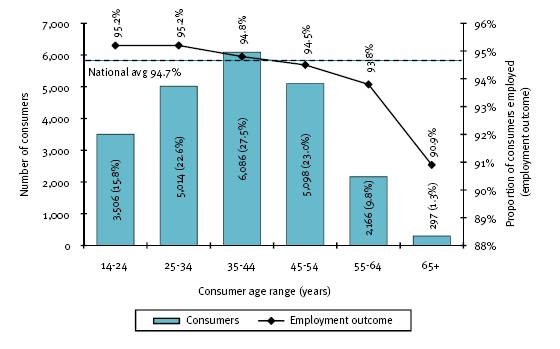

- Figure 4.15: All disability employment service consumers with an employment outcome, by age, 2007-08

- Figure 4.16: All open employment service consumers, by age group, 2007-08

- Figure 4.17: All open employment service consumers, by country of birth category, 2007-08

- Figure 4.18: All open employment service consumers, by state or territory of usual residence, 2007-08

- Figure 4.19: All open employment service consumers, by primary disability type, 2007-08

- Figure 4.20: All open employment service consumers with an other significant disability, by other significant disability type, 2007-08

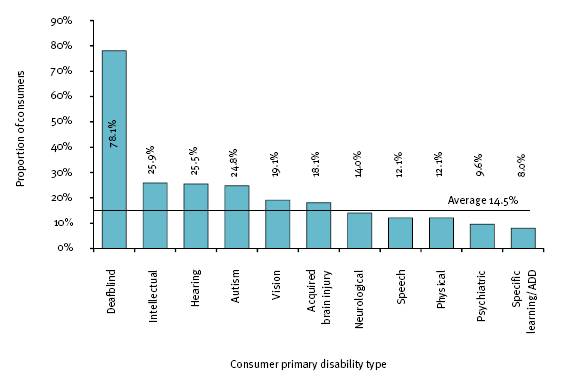

- Figure 4.21: All open employment service consumers, by severity of disability, 2007-08

- Figure 4.22: All open employment service consumers with a profound or severe core activity limitation, by primary disability type, 2007-08

- Figure 4.23: All open employment service consumers who always or sometimes needed support, by main life area, 2007-08

- Figure 4.24: All open employment service consumers, by relationship of informal carer to consumer, 2007-08

- Figure 4.25: All open employment service consumers, by main source of income, 2007-08

- Figure 4.26: All open employment service consumers, by equity group and employment outcome, 2007-08

- Figure 4.27: All open employment service consumers, by age and employment outcome, 2007-08

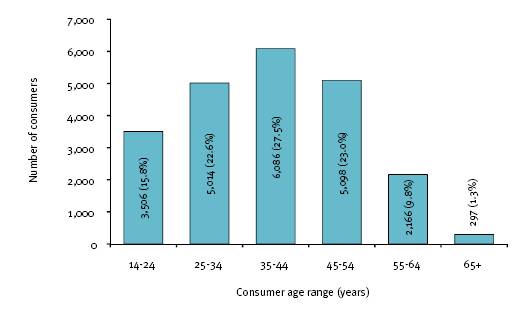

- Figure 4.28: All supported employment service consumers, by age group, 2007-08

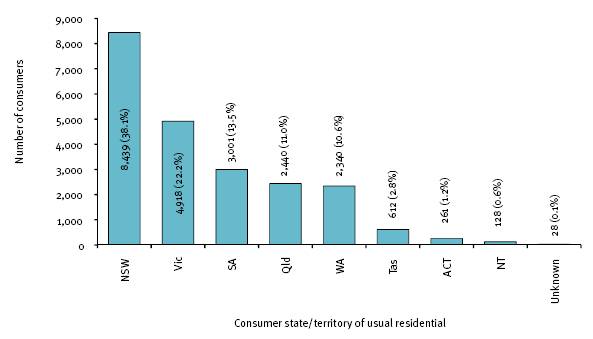

- Figure 4.29: All supported employment service consumers, by state or territory of usual residence, 2007-08

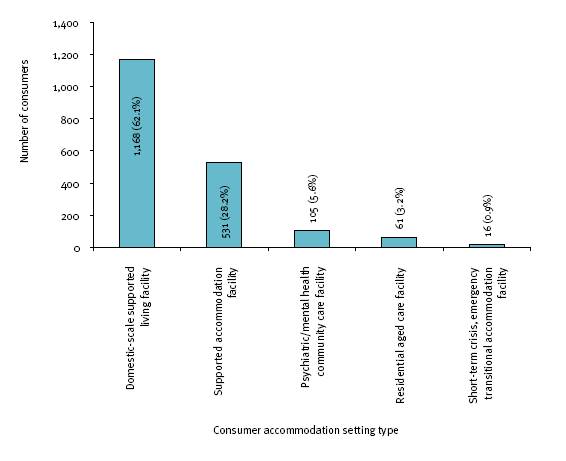

- Figure 4.30: All supported employment service consumers that are in supported accommodation, by supported accommodation setting, 2007-08

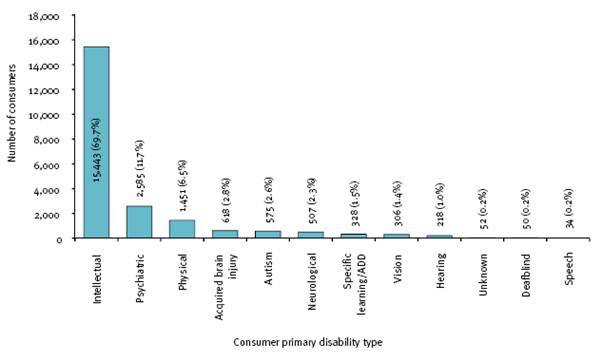

- Figure 4.31: All supported employment service consumers, by primary disability type, 2007-08

- Figure 4.32: All supported employment service consumers with another significant disability, by other significant disability type, 2007-08

- Figure 4.33: All supported employment service consumers, by severity of disability, 2007-08

- Figure 4.34: All supported employment service consumers with a profound or severe core activity limitation, by primary disability type, 2007-08

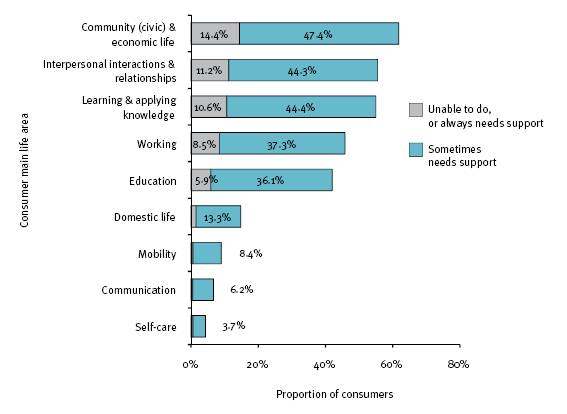

- Figure 4.35: All supported employment service consumers who always or sometimes needed support, by main life area, 2007-08

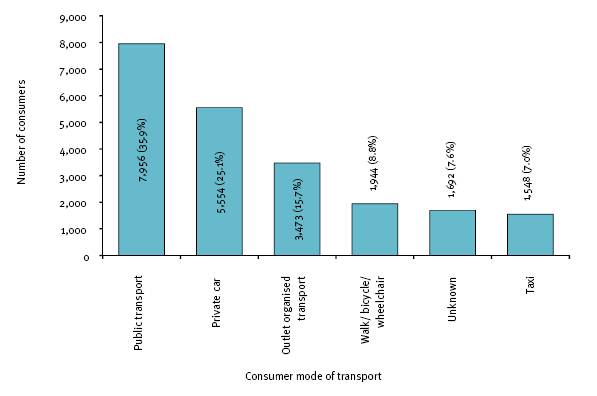

- Figure 4.36: All supported employment service consumers, by mode of transport used to get to their place of work, 2007-08

- Figure 4.37: All supported employment service consumers, by geographic location of usual residence and mode of transport used to get to their place of work, 2007-08

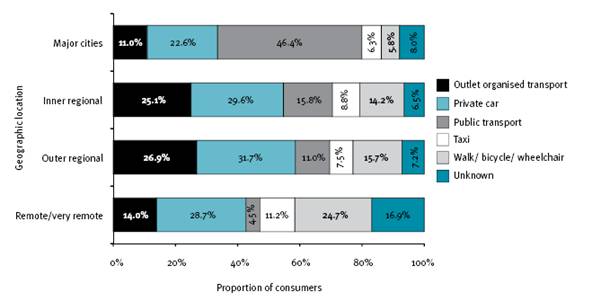

- Figure 4.38: All supported employment service consumers, by relationship of informal carer to consumer, 2007-08

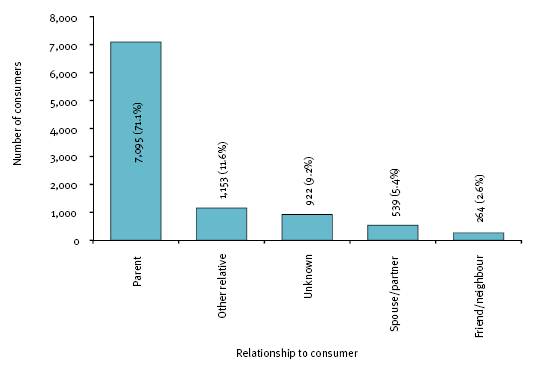

- Figure 4.39: All supported employment service consumers, by age and employment outcome, 2007-08

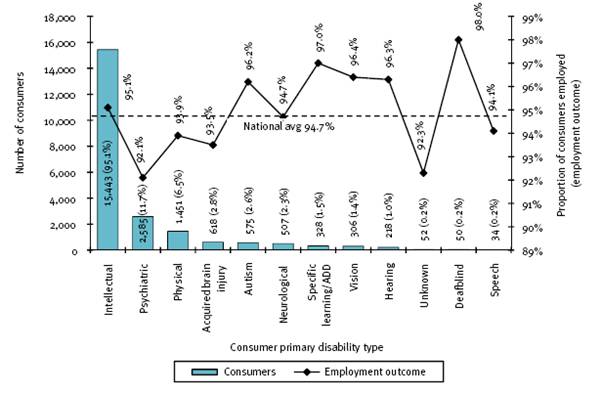

- Figure 4.40: All supported employment service consumers, by primary disability type and employment outcome, 2007-08

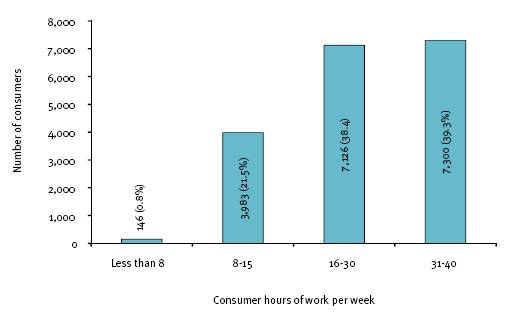

- Figure 4.41: Supported employment service consumers ‘on the books’, by standard hours worked per week, 30 June 2008

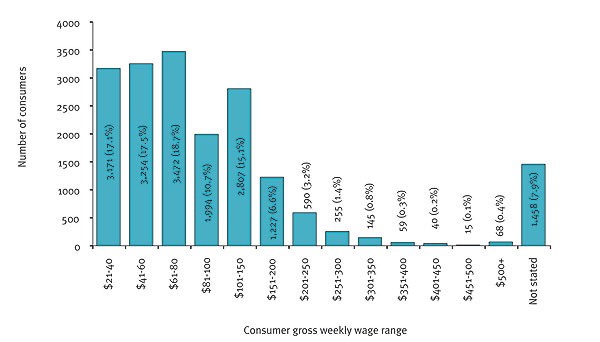

- Figure 4.42: Supported employment service consumers ‘on the books’, by gross weekly wage category, 30 June 2008

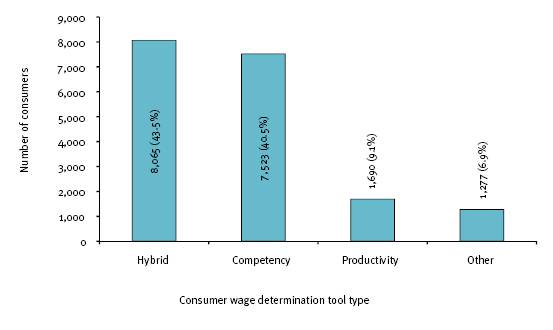

- Figure 4.43: Supported employment service consumers ‘on the books’, by measure used to determine wage, 30 June 2008

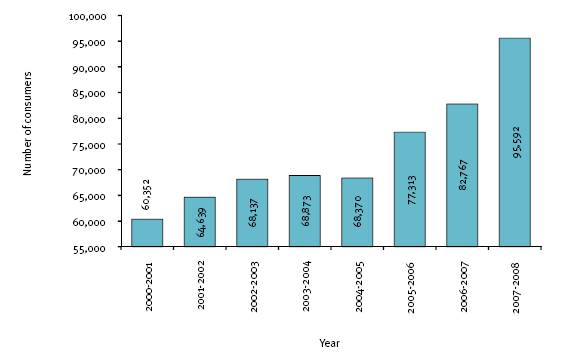

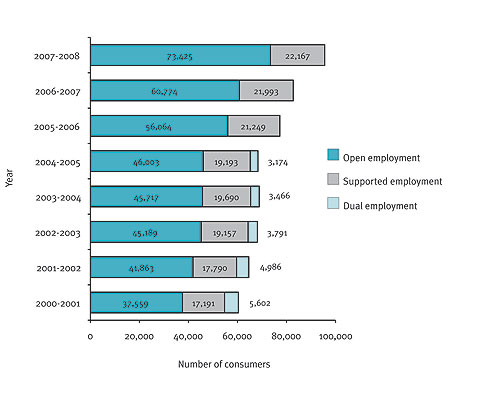

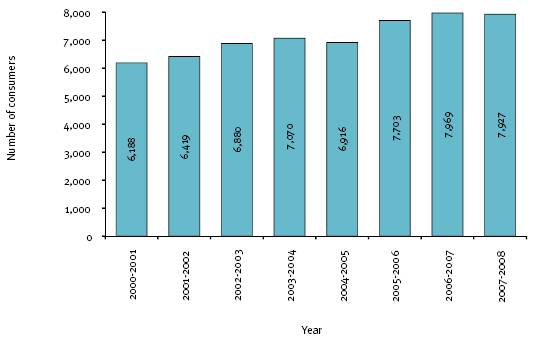

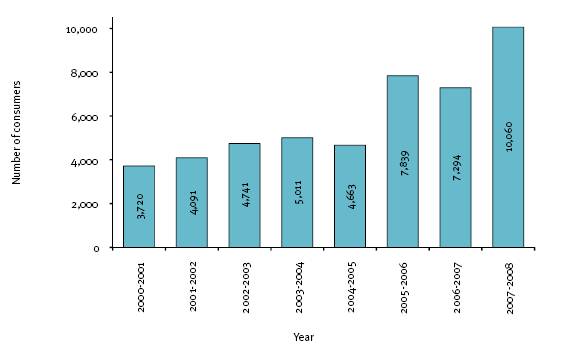

- Figure 5.1: Consumers accessing disability employment services, 2000-01 to 2007-08

- Figure 5.2: Consumers accessing disability employment services, by employment service type, 2000-01 to 2007-08

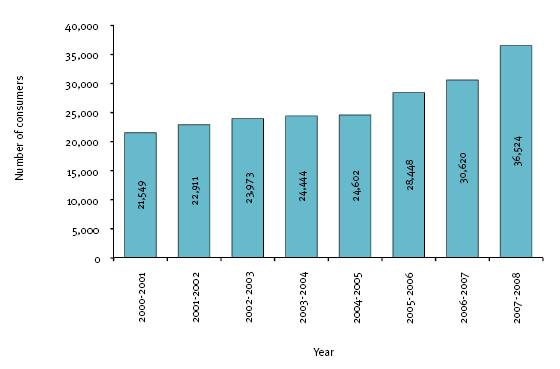

- Figure 5.3: Female consumers accessing disability employment services, 2000-01 to 2007-08

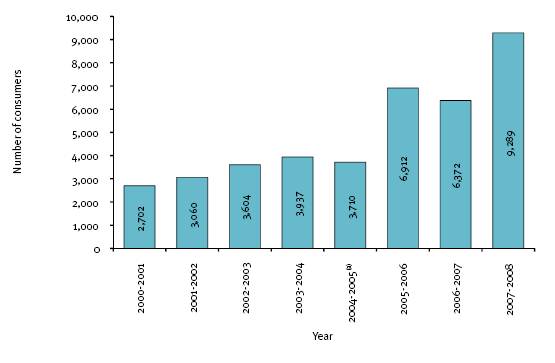

- Figure 5.4: Female consumers accessing open employment services, 2000-01 to 2007-08

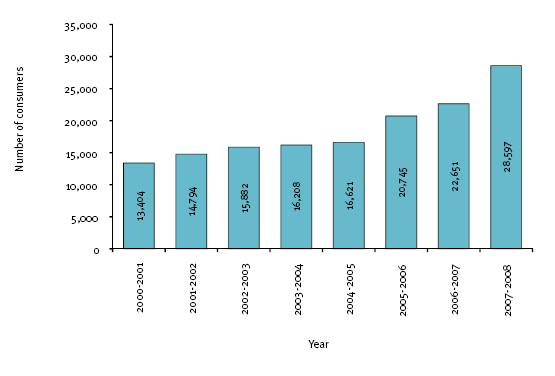

- Figure 5.5: Female consumers accessing supported employment services, 2000-01 to 2007-08

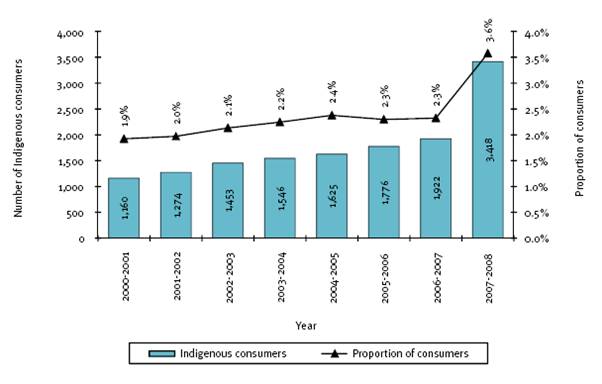

- Figure 5.6: Indigenous consumers accessing disability employment services, 2000-01 to 2007-08

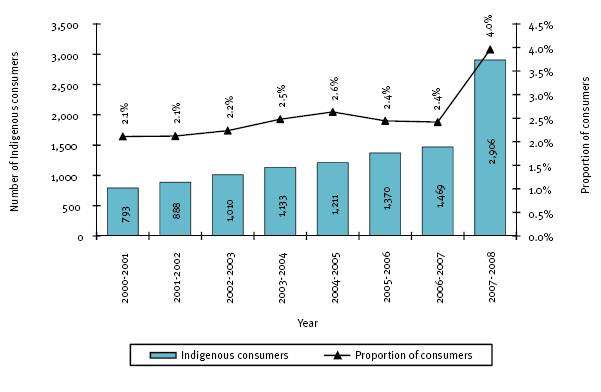

- Figure 5.7: Indigenous consumers accessing open employment services, 2000-01 to 2007-08

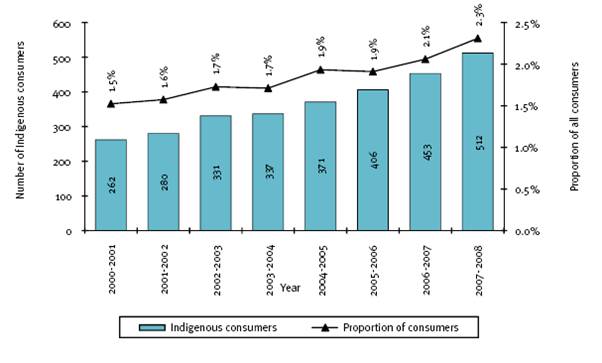

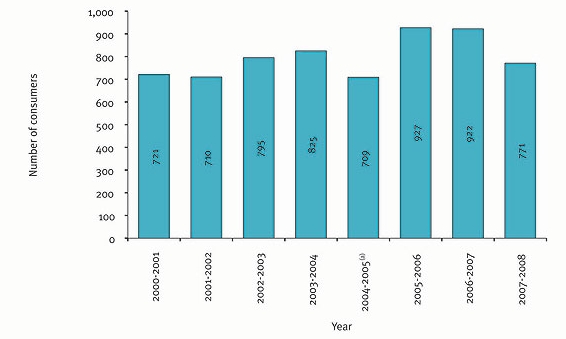

- Figure 5.8: Indigenous consumers accessing supported employment services, 2000-01 to 2007-08

- Figure 5.9: Consumers from non-English speaking backgrounds accessing disability employment services, 2000-01 to 2007-08

- Figure 5.10: Consumers from non-English speaking backgrounds accessing open employment services, 2000-01 to 2007-08

- Figure 5.11: Consumers from non-English speaking backgrounds accessing supported employment services, 2000-01 to 2007-08

Acknowledgements

The Disability and Carers Payments Branch in the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) had overall responsibility for the 2008 Disability Services Census. The collection of the disability services census data was shared between FaHCSIA and the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) in line with their management and funding responsibilities. FaHCSIA collected information on all disability service types except for open employment services and DEEWR collected open employment service outlet and consumer data.

FaHCSIA acknowledges that this report would not have been possible without the valued cooperation and effort of disability service providers.

Chapter One: Executive Summary

- 1.1 Background

- 1.2 Outline of the Report

- 1.3 Main counts and definitions

- 1.4 Summary of main findings

- 1.5 Data summary of all disability service outlets, 2007-08

- 1.5a Data summary of disability employment services, 2007-08

- 1.5b Data summary of open employment services, 2007-08

- 1.5c Data summary of supported employment services, 2007-08

- 1.5d Data summary of advocacy services, 2007-08

- 1.5e Data summary of respite services, 2007-08

- 1.5f Data summary of print disability services, 2007-08

- 1.5g Data summary of information services, 2007-08

1.1 Background

The 2008 Disability Services Census, which covers all CSTDA services funded by the Australian Government in 2007-08, was collected under the third and final Commonwealth State Territory Disability Agreement (CSTDA) to inform national reporting processes. Under the CSTDA the Australian Government was responsible for the planning, policy setting and management of specialist disability employment assistance. The Australian Government shared similar responsibilities with State and Territory Governments for advocacy, respite, print disability and information services. The Disability Services Act 1986 (Cth) provides the legislative framework for the funding and delivery of Australian Government funded disability services.

The new National Disability Agreement (NDA), effective from 1 January 2009, now provides the national framework and key areas of reform for the provision of government support and services for people with disability. The NDA between the Australian Government and State and Territory Governments will improve and increase services for people with disability, their families and carers.

The NDA is part of a broader National Disability Reform Agenda and will in future come under the National Disability Strategy, which is currently being developed. The reforms are directed at creating a disability services system that is effective, efficient and equitable and that has a focus on early intervention; timely, person-centred approaches; and lifelong planning.

The Parties have agreed to concentrate initial national efforts in several identified priority areas to underpin the policy directions and achieve reforms in the disability service system. They are:

- Better Measurement of Need – Under this priority: a national model to estimate demand will be developed by mid 2010; there will be improvements in the data collected through the Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers (SDAC), providing a stronger basis for demand estimates; and improvements in the quality of data reported under the National Minimum Data Set and jurisdiction-level unmet demand data.

- Population Benchmarking for Disability Services – A National Population Benchmarking Framework will be developed and initial population benchmarking of disability services, based on information available, will be achieved by mid 2010 to improve the evidence base to assist in policy, service and planning decisions.

- Making Older Carers a Priority – The National Disability Priorities Framework will assist Governments to target services to more vulnerable population groups based on relative need (including older carers and Indigenous people with disability).

- Quality Improvement Systems based on Disability Standards – A National Disability Quality Framework with a National Quality Assurance system for disability services will be developed to introduce a national approach to quality assurance and the continuous improvement of disability services by mid 2010.

- Service Planning and Strategies to Simplify Access – The National Framework for Service Planning and Access will be developed, focusing on providing a person centered approach to service delivery and to simplify access to specialist disability services.

- Early Intervention and Prevention, Lifelong Planning and Increasing Independence and Social Participation Strategies – An Early Intervention and Prevention Framework will be developed to increase Governments’ effectiveness in early intervention and prevention strategies and to ensure that clients receive the most appropriate and timely support by mid 2011.

- Increased Workforce Capacity – A national workforce strategy will be developed to address qualifications, training and cross sector career mapping issues and establishing the disability sector as an ‘industry of choice’ by the end of 2010.

- Increased Access for Indigenous Australians – A National Indigenous Access Framework will ensure that the needs of Indigenous Australians with disability are addressed through appropriate service delivery arrangements.

- Access to Aids and Equipment – More consistent access to aids and equipment by the end of 2012.

- Improved Access to Disability Care – Systems that improve access to disability care and ensure people are referred to the most appropriate disability services and supports, including consideration of single access points and nationally consistent assessment processes in line with nationally agreed principles by end 2011.

Under the NDA all Governments have agreed to the provision of data, including a commitment to providing data for the National Minimum Data Set and a commitment to the improvement of data. This includes the continuation of the annual Disability Services Census. The Australian Government is responsible for disability employment services, delivered by both open and supported employment services, and assists State and Territory Governments with funding for the provision of specialist disability services.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

1.2 Outline of the Report

This report comprises eight chapters. Chapter One includes the executive summary, which outlines the purpose of the report and summarises the main findings from the 2008 Disability Services Census collection. Summary statistics are also provided at the end of the chapter. Chapter Two provides a history of the Disability Services Census. Chapter Three provides a profile of the operations of Australian Government funded CSTDA services. Chapter Four provides a profile of the characteristics of consumers accessing disability employment services. Separate commentary is also provided on the characteristics of consumers accessing open and supported employment services. Chapter Five provides trends series data and commentary on changes in the profile of disability employment service consumers over time. Chapter Six presents state and territory summary statistics on disability service outlets and disability employment service consumers. Chapter Seven contains the Appendices, which provide more detailed data tables. Chapter eight contains the glossary of terms.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

1.3 Main counts and definitions

The main counts in the 2008 Disability Services Census collection are disability service outlet, disability service type and consumer:

- A disability service outlet is an administrative business or unit of an organisation that is funded to provide a CSTDA service type at a particular site. The organisation may be a single disability service outlet or an aggregation of two or more disability service outlets of the same or different disability service type. The 2008 Disability Services Census collected data on each disability service outlet that operated during 2007-08.

- Disability service type is the type of service the disability service outlet has been funded to provide under the CSTDA. Under the CSTDA, the Australian Government funds disability service outlets to provide open employment, supported employment, advocacy, respite, print disability and information services.

- A consumer is a person who accesses an Australian Government funded CSTDA service outlet. The 2008 Disability Services Census collected data on the number of consumers assisted in all disability service types in 2007-08.

Separate data was collected for each consumer assisted by open and supported employment service outlets in 2007-08. This group is referred to as ‘All consumers’. Data was also collected for each consumer who was registered as receiving assistance from open and supported service outlets on Census Day, 30 June 2008. This group is referred to as ‘Consumers on the books’.

Where consumers of open and supported employment service outlets had more than one service episode or spell in 2007-08, the following scenarios and corresponding counts were applied:

- Where a consumer exited a service outlet and re-entered the same service outlet within the same financial year, the consumer was counted once. The records of these consumers were treated as duplicate records.

- Where a consumer exited a service outlet and entered another service outlet of the same service type, the consumer was counted each time a move occurred.

- Where a consumer exited a service outlet and entered another service outlet of a different service type, the consumer was counted each time a move occurred.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

1.4 Summary of main findings

1.4.1 Disability service outlet profile

In 2007-08, a total of 1201 disability service outlets received funding from the Australia Government under the CSTDA, a reduction of nine (0.8%) disability service outlets since 2006-07.

The vast majority (1,075 or 89.5%) of disability service outlets provided specialist disability employment assistance, with 662 (55.1%) providing open employment assistance and 413 (34.4%) supported employment assistance (including targeted employment). A further 68 (5.7%) disability service outlets provided advocacy services, 46 (3.8%) respite services, 10 (0.8%) print disability services and two (0.2%) information services.

Importantly, based on the major city/non-major city breakdown of the general Australian population, there was a good balance of disability service outlets located in regional and remote areas (43.1%). Disability service outlets providing open employment and supported employment operated in metropolitan, regional and remote locations.

Most disability service outlets operated 7-8 hours a day (76.3%), five days a week (80.2%), for 48 or more weeks in the year (92.4%), with 50.0% (601) operating the full 52 weeks in 2007-08.

A total of 287,864 paid staff hours in the reference week were spent on disability service outlet operations in 2007-08. Based on a 38-hour working week, a total of 7,575 FTE paid staff worked in disability service outlets across Australia in 2007-08. This equates to an average of 6.3 FTE paid staff in each disability service outlet. There were 1,443 (16.0%) less FTE paid staff working in disability service outlets in 2007-08 than were in 2006-07, down from 9,018. Almost half FTE paid staff worked in the open employment sector, some 3,436 (49.0%).

Disability service outlets also reported 8,225 hours of volunteer support in a typical week in 2007-08, or an equivalent of another 216 FTE staff. This represents 2.9% of paid staff hours. Print disability services were most likely to use the support of volunteers to supplement day-to-day service outlet operations, with volunteer support hours representing 34.5% of paid staff hours.

1.4.2 Number of consumers assisted

In 2007-08, a total of 165,340 consumers were assisted through Australian Government funded CSTDA services. Just over half (95,592 or 57.8%) of all consumers accessed specialist disability employment assistance, of whom 73,425 (44.4%) used open employment services and 22,167 (13.4%) used supported employment services. A further 34,100 (20.6%) consumers used information services, 29,836 (18.0%) used print disability services, 5,812 (3.5%) used respite services, while no data was collected on advocacy services.

1.4.3 Characteristics of disability employment service consumers

Among the 95,592 disability employment service consumers in 2007-08, the majority were male (61.8%). Their median age was 37 years. Disability employment services assisted a total of 3,418 (3.6%) Indigenous consumers, 10,060 (10.5%) consumers born in non-English speaking countries and 32,041 (33.5%) consumers living in regional and remote areas.

Consumers were most likely to have an intellectual disability (28.4%), followed by a psychiatric disability (27.0%) and physical disability (21.7%). Some 27.7% of consumers had a profound or severe core activity limitation. The main life areas in which consumers always or sometimes needed support were learning and applying knowledge (62.7%), interpersonal interactions and relationships (60.6%) and working (56.6%). Around one-sixth (16.6%) of consumers had an informal carer.

A government pension or allowance was the main source of income for over three-quarters (79.6%) of consumers, with the majority (52.0%) receiving a disability support pension. Paid employment was the main source of income for 3.3% of consumers.

There were significant differences in the characteristics of open and supported employment service consumers in 2007-08. For instance:

- Open employment service consumers were younger on average, with 47.1% under the age of 35 years, compared with 38.4% of supported employment service consumers.

- The representation of Indigenous consumers was higher in open than in supported employment services (4.0% compared with 2.3%).

- The representation of consumers from non-English speaking backgrounds was higher in open than in supported employment services (12.7% compared with 3.5%).

- A slightly higher percentage of open than supported employment service consumers were living in regional and remote areas (35.8% compared with 32.9%).

- Consumers with a psychiatric disability were the largest group using open employment services (31.7%), whereas consumers with an intellectual disability were the largest group using supported employment services (69.7%).

- A considerably higher percentage of open than supported employment service consumers had multiple or other significant disabilities (46.1% compared with 31.4%).

- The percentage of consumers with a profound or severe core activity limitation was much higher among supported than open employment service consumers (71.8% compared with 14.5%).

- Open employment service consumers were most likely to need support with community (civic) and economic life (61.8%), whereas supported employment service consumers were most likely to need support with working (92.6%).

- Supported employment service consumers were much more likely to have in place formal and informal care arrangements than open employment service consumers.

- Some 8.5% of supported employment service consumers were living in settings where supported accommodation or formal care is provided, compared with 0.8% of open employment service consumers.

- Supported employment service consumers were five times as likely as open employment service consumers to have an informal carer (45.0% compared with 8.0%).

- Supported employment service consumers were much more likely than open employment service consumers to receive a government pension or allowance as their main source of income (98.7% compared with 73.8%).

1.4.4 Employment outcomes

The provision of specialist disability employment assistance continues to provide invaluable assistance to people with disability who need assistance to enter and remain in the workforce. Throughout 2007-08, disability employment services delivered strong employment outcomes overall for consumers.

‘Employment outcomes’ refers to those consumers in disability employment services who were employed for some or all of the time during 2007-08. It differs from, and should not be confused with, the employment outcome measure applying to the case-based funding model for disability employment services, which uses an hours and duration in employment measure.

In 2007-08, employment outcomes data illustrated that 20,995 (94.7%) supported employment consumers and 36,857 (50.2%) open employment consumers obtained an employment outcome.

The highest employment outcome for supported and open employment were attained by those who had a deafblind disability (98.0%) and intellectual (72.8%) respectively.

Supported employment consumers with the following disabilities achieved a marginally higher employment outcome than the national average (94.7%): specific learning/Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD) (97.0%), vision (96.4%), hearing (96.3%), autism (96.2%), and intellectual disability (95.1%). The employment outcome attained by consumers with a neurological disability was in line with the national average. Open employment consumers with the following disabilities achieved employment outcomes above the national average: intellectual disability (72.8%), deafblind (65.6%), hearing (63.8%), speech (62.7%), specific learning/ADD (59.7%), autism (59.0%), acquired brain injury (58.6%), vision (56.0%), and neurological disability (50.9%). Many consumers from equity groups also faced challenges in obtaining employment. For instance:

- The employment outcomes for female consumers:

- supported employment (94.6%), was equal to that of male counterparts. Even though female consumers attained an equal employment outcome to males as a group they remain significantly under-represented in supported employment services, accounting for only 35.8% of all consumers, while,

- females in open employment services had a slightly lower outcome to that of their male counterparts, 47.3% and 52.1% respectively.

- Indigenous consumers represented 2.3% of supported employment and 4.0% of open employment consumers. Supported employment Indigenous consumers attained an employment outcome of 91.0%, which is 3.7 percentage points lower than the national average. Open employment Indigenous consumers attained an employment outcome of 38.5%, some 11.7 percentage points below the national average for open employment consumers.

- Consumers born in a non-English speaking country represented 3.5% of supported employment consumers and 12.7% of open employment consumers. Supported employment non-English speaking consumers attained an employment outcome of 95.1%, which is 2.6 percentage points lower than the national average, while open employment non-English speaking consumers attained an employment outcome of 31.7%, which is 18.5 percentage points below the national average for open employment consumers.

- Consumers living in regional and remote areas were well represented in supported employment services (31.4%) and open employment (23.5%). Supported employment consumers living in regional and remote areas attained a marginally lower employment outcome than their major city counterparts (93.5% compared with 95.3%), while open employment consumers living in regional and remote areas attained a slightly higher employment outcome to that of their major city counterparts (51.3% compared to 49.6%).

1.4.5 Reliability of data

Sampling error

Sampling errors are a measure of the variability that occurs by chance because a sample, rather than the entire population, is surveyed. As a full collection of data on Australian Government funded CSTDA service outlets was undertaken, sampling error does not apply to the 2008 Disability Services Census collection.

Non-sampling error

Non-sampling errors may occur in any statistical collection during data recording, processing and reporting. There are two major sources of non-sampling error relevant to the 2008 Disability Services Census:

- Response error on the part of the disability service outlet. These errors may arise through misunderstanding or misinterpretation of responses required, inability or unwillingness to provide accurate information and mistakes in answers to questions.

A number of processes were put in place to minimise the incidence of response errors. These included assistance to disability service outlets through a telephone help line, stringent checking and editing processes for all disability service outlet and consumer data and follow-up with disability service outlets of census return information. These measures have minimised the potential incidence of response errors.

- Errors arise through the data entry process on the part of the disability service outlet and FaHCSIA and DEEWR during the collation of Disability Services Census data.

Data entry errors have been minimised with the continued use of the electronic Disability Services Census collection and upload systems. Electronic disability service outlet returns were entered directly into the upload system (without keying) where quality control checking and editing were automatically performed.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

1.5 Data summary of all disability service outlets, 2007-08

No. of service outlets funded in the year

- 1,201 CSTDA service outlets were funded by the Australian Government in 2007-08

- nine less CSTDA disability service outlets operated in 2007-08 than in 2006-07

Service outlet type

- 1,075 (86.3%) disability employment services

- 662 (55.1%) open employment services

- 413 (34.4%) supported employment services

- 68 (5.7%) advocacy services

- 46 (3.8%) respite services

- 10 (0.8%) print disability services

- 2 (0.2%) information services

State distribution of service outlets

- 418 (34.8%) in New South Wales

- 280 (23.3%) in Victoria

- 199 (16.6%) in Queensland

- 124 (10.3%) in South Australia

- 98 (8.2%) in Western Australia

- 39 (3.2%) in Tasmania`

- 23 (1.9%) in the Australian Capital Territory

- 20 (1.7%) in the Northern Territory

Geographic location of service outlets

- 675 (56.9%) in major cities

- 477 (40.2%) in regional areas

- 35 (2.9%) in remote areas

Service outlet period of operation

- 916 (76.3%) operated 7-8 hours a day

- 963 (80.2%) operated 5 days a week

- 1,110 (92.4%) operated 48-52 weeks in the year

No. of FTE paid staff in the reference week (Based on a 38-hour working week)

- 7,575 FTE staff assisted in Australian Government funded CSTDA services

- 1,443 (16.0%) less FTE staff worked in 2007-08 than in 2006-07

No. of FTE paid staff in each service type (Based on a 38-hour working week)

- 7,148 (94.4%) FTE staff in disability employment services

- 3,712(49.0%) FTE staff in open employment services

- 3,413 (45.0%) FTE staff in supported employment services

- 152 (2.0%) FTE staff worked in advocacy services

- 180 (2.4%) FTE staff worked in respite services

- 94 (1.2%) FTE staff in print disability services

- 2 (0.0%) FTE staff in information services

No. of volunteers in a typical week

- 216 FTE volunteers in disability service outlet operations

No. of consumers assisted in the year

- 165,340 consumers were assisted by Australian Government funded CSTDA services

No. of consumers assisted in each service type in the year

- 95,592 (66.8%) used disability employment services

- 73,425 (51.3%) used open employment services

- 22,167 (15.5%) used supported employment services

- 34,100 (23.8%) used information services

- 29,836 (20.9%) used print disability services

- 5,812 (4.1%) used respite services

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

1.5a Data summary of disability employment services, 2007-08

No. of service outlets funded in the year

- 1,075 disability employment service outlets

- 89.5% of all disability service outlets

- 3 (0.3%) more disability employment service outlets operated in 2007-08 than in 2006-07

State distribution of service outlets

- 385 (35.8%) in New South Wales

- 250 (23.2%) in Victoria

- 184 (17.1%) in Queensland

- 113 (10.5%) in South Australia

- 79 (7.3%) in Western Australia

- 32 (3.0%) in Tasmania

- 18 (1.7%) in the Australian Capital Territory

- 14 (1.3%) in the Northern Territory

Geographic location of service outlets

- 675 (56.9%) in major cities

- 477 (40.2%) in regional areas

- 35 (2.9%) in remote areas

Service outlet period of operation

- 852 (79.3%) operated 7-8 hours a day

- 963 (80.2%) operated 5 days a week

- 1,110 (92.4%) operated 48-52 weeks in the year

No. of FTE paid staff in the reference week (Based on a 38-hour working week)

- 7,148 FTE staff worked in disability employment service outlets

- 94.4% of all disability service outlet staff

- 6.6 FTE staff per disability employment service outlet (average)

- Each consumer received 2.8 total staff hours per week (average)

No. of volunteers in a typical week

- 136 FTE volunteers assisted in disability employment service outlet operations

- 62.9% of all disability service outlet volunteers

No. of consumers assisted in the year

- 95,592 used disability employment services

- 66.8% of all consumers assisted across all disability service outlets

Consumer characteristics

Equity group representation

- 36,524 (38.2%) female consumers

- 3,418 (3.6%) Indigenous consumers

- 10,060 (10.5%) NESB consumers

- 32,041 (33.5%) regional & remote consumers

Disability information

- 27,195 (28.4%) had an intellectual disability

- 25,828 (27.0%) had a psychiatric disability

- 20,785 (21.7%) had a physical disability

- 7,232 (7.6%) had a learning disability

- 3,128 (3.3%) had autism

- 3,030 (3.2%) had a neurological disability

- 2,838 (3.0%) had a hearing disability

- 2,685 (2.8%) had an acquired brain injury

- 26,542 (27.8%) had a profound or severe core activity limitation

- 2,450 (2.6%) lived in supported accommodation

- 15,861 (16.6%) had an informal carer

Main source of income and employment

- 76,067 (79.6%) received a government pension or allowance

- 49,686 (52.0%) received DSP

- 3,109 (3.3%) had paid employment as their main source of income

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

1.5b Data summary of open employment services, 2007-08

No. of service outlets funded in the year

- 662 open employment service outlets

- 55.1% of all disability service outlets

- 5 (0.7%) more open employment service outlets operated in 2007-08 than in 2006-07

State distribution of service outlets

- 229 (34.6%) in New South Wales

- 149 (22.5%) in Victoria

- 134 (20.2%) in Queensland

- 70 (10.6%) in South Australia

- 45 (6.8%) in Western Australia

- 17 (2.6%) in Tasmania

- 9 (1.4%) in the Australian Capital Territory

- 9 (1.4%) in the Northern Territory

Geographic location of service outlets

- 363 (55.3%) in major cities

- 273 (40.2%) in regional areas

- 21 (3.2%) in remote areas

Service outlet period of operation

- 551 (83.2%) operated 7-8 hours a day

- 565 (85.3%) operated 5 days per week

- 610 (97.1%) operated 48-52 weeks in the year

No. of FTE paid staff in the reference week (Based on a 38-hour working week)

- 3,712 FTE staff assisted in open employment service outlets

- 49.0% of all disability service outlet staff

- 5.6 FTE staff per outlet (average)

- Each consumer received 1.9 total staff hours per week (average)

No. of volunteers in a typical week

- 35 FTE volunteers in open employment service outlet operations

- 16.2% of all disability service outlet volunteers

No. of consumers assisted in the year

- 73,425 used open employment services

- 44.4% of all consumers assisted across all disability service outlets

Consumer characteristics

Equity group representation

- 28,597 (38.9%) female consumers

- 2,906 (4.0%) Indigenous consumers

- 9,289 (12.7%) NESB consumers

- 26,280 (35.8%) regional & remote consumers

Disability information

- 23,243 (31.7%) had a psychiatric disability

- 19,334 (26.3%) had a physical disability

- 11,752 (16.0%) had an intellectual disability

- 6,904 (9.4%) had a learning disability

- 4,722 (6.4%) had a sensory disability

- 2,553 (3.5%) had autism

- 2,523 (3.4%) had a neurological disability

- 2,067 (2.8%) had an acquired brain injury

- 10,630 (14.5%) had a profound or severe core activity limitation

- 5,888 (8.0%) had an informal carer

Main source of income and employment

- 54,198 (73.8%) received a government pension or allowance

- 28,041 (38.2%) received DSP

- 3,020 (4.1%) had paid employment as their main source of income

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

1.5c Data summary of supported employment services, 2007-08

No. of service outlets funded in the year

- 413 supported employment service outlets

- 34.4% of all disability service outlets

State distribution of service outlets

- 156 (37.8%) in New South Wales

- 101 (24.5%) in Victoria

- 50 (12.1%) in Queensland

- 43 (10.4%) in South Australia

- 34 (8.2%) in Western Australia

- 15 (3.6%) in Tasmania

- 9 (2.2%) in the Australian Capital Territory

- 5 (1.2%) in the Northern Territory

Geographic location of service outlets

- 232 (56.7%) in major cities

- 167 (40.8%) in regional areas

- 10 (2.4%) in remote areas

Service outlet period of operation

- 301 (72.9%) operated 7-8 hours a day

- 326 (78.9%) operated 5 days per week

- 360 (87.2%) operated 48-52 weeks in the year

Note: data was not provided in respect of two supported employment service outlets

No. of FTE paid staff in the reference week (Based on a 38-hour working week)

- 3,436 FTE staff worked in supported employment service outlets

- 45.4% of all disability service outlet staff

- Indirect/direct support staff ratio is 1:2

- 8.3 FTE staff per outlet (average)

- Each consumer received 6.1 total direct staff support hours per week (average)

No. of volunteers in a typical week

- 102 FTE volunteers assisted in supported employment service outlet operations

- 46.9% of all disability service outlet volunteers

No. of consumers assisted in the year

- 22,167 used supported employment services

- 13.4% of all consumers assisted across all disability service outlets

- 54 consumers per outlet (average)

Consumer characteristics

Equity group representation

- 7,927 (35.8%) female consumers

- 512 (2.3%) Indigenous consumers

- 771 (3.5%) NESB consumers

- 7,142 (32.2%) regional & remote consumers

Disability information

- 15,443 (69.7%) had an intellectual disability

- 2,585 (11.7%) had a psychiatric disability

- 1,451 (6.5%) had a physical disability

- 618 (2.8%) had an acquired brain injury

- 574 (2.6%) had a sensory disability

- 575 (2.6%) had autism

- 507 (2.3%) had a neurological disability

- 328 (1.5%) had a learning disability

- 15,912 (71.8%) had a profound or severe core activity limitation

- 9,973 (45.0%) had an informal carer

- 1,881 (8.5%) lived in supported accommodation

Main source of income and employment

- 21,645 (97.6%) received DSP

- 20,995 (94.7%) were employed in 2007-08

Employment characteristics

- 29.1% worked full-time hours

- 25.6 hours worked per week (average)

- 64.1% earned $100 or less a week

- $93.16 gross weekly wage (average)

- $3.74 gross hourly wage rate (average)

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

1.5d Data summary of advocacy services, 2007-08

No. of service outlets funded in the year

- 68 advocacy service outlets

- 5.7% of all disability service outlets

State distribution of service outlets

- 16 (23.5%) in New South Wales

- 21 (30.9%) in Victoria

- 8 (11.8%) in Queensland

- 6 (8.8%) in South Australia

- 9 (13.2%) in Western Australia

- 3 (4.4%) in Tasmania

- 2 (2.9%) in the Australian Capital Territory

- 3 (4.4%) in the Northern Territory

Geographic location of service outlets

- 47 (70.1%) in major cities

- 18 (26.9%) in regional areas

- 2 (3.0%) in remote areas

Service outlet period of operation

- 46 (67.6%) operated 7-8 hours a day

- 47 (69.1%) operated 5 days per week

- 53 (77.9%) operated 48-52 weeks in the year

No. of FTE paid staff in the reference week (Based on a 38-hour working week)

- 152 FTE staff worked in advocacy service outlets

- 2.0% of all disability service outlet staff

- 2.2 FTE staff per outlet (average)

No. of volunteers in a typical week

- 46 FTE volunteers assisted in advocacy service outlet operations

- 21.2% of all disability service outlet volunteers

- Volunteers represented 30.3% of paid staff hours in advocacy services

- second highest across all disability service types

- 0.7 FTE volunteers per outlet (average)

Note: Advocacy consumer data was not collected for 2007-08.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

1.5e Data summary of respite services, 2007-08

No. of service outlets funded in the year

- 46 respite service outlets

- 3.8% of all disability service outlets

State distribution of service outlets

- 14 (30.4%) in New South Wales

- 7 (15.2%) in Victoria

- 6 (13.0%) in Queensland

- 4 (8.7%) in South Australia

- 8 (17.4%) in Western Australia

- 3 (6.5%) in Tasmania

- 1 (2.2%) in the Australian Capital Territory

- 3 (6.5%) in the Northern Territory

Geographic location of service outlets

- 22 (52.5%) in major cities

- 18 (42.9%) in regional areas

- 2 (4.8%) in remote areas

Service outlet period of operation

- 10 (21.7%) operated 7-8 hours a day

- 18 (39.1%) operated 24 hours a day

- 15 (32.6%) operated 5 days per week

- 18 (39.1%) operated 7 days a week

- 45 (97.8%) operated the full 52 weeks in the year

No. of FTE paid staff in the reference week (Based on a 38-hour working week)

- 180 FTE staff worked in respite services

- 2.4% of all disability service outlet staff

- 4.0 FTE staff per outlet (average)

- Each consumer received 1.2 total staff hours in the year (average)

No. of volunteers in a typical week

- 2 FTE volunteers assisted in respite service outlet operations

- 0.8% of all disability service outlet volunteers

No. of consumers assisted in the year

- 5,812 used respite services

- 3.5% of all consumers assisted across all disability service outlets

- 126 consumers per respite outlet (average)

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

1.5f Data summary of print disability services, 2007-08

No. of service outlets funded in the year

- 10 print disability service outlets

- 0.8% of all disability service outlets

State distribution of service outlets

- 2 (20.0%) in New South Wales

- 2 (20.0%) in Victoria

- 1 (10.0%) in Queensland

- 1 (10.0%) in South Australia

- 2 (20.0%) in Western Australia

- 1 (10.0%) in Tasmania

- 1 (10.0%) in the Australian Capital Territory

- There are no print disability service outlets operating in the Northern Territory

Geographic location of service outlets

- 9 in major cities

- 1 in regional areas

- There were no print disability service outlets operating in remote areas

Service outlet period of operation

- 6 operated 7-8 hours a day

- 8 operated 5 days per week

- 7 operated 48-52 weeks in the year

No. of FTE paid staff in the reference week (Based on a 38-hour working week)

- 94 FTE staff worked in respite services

- 1.2% of all disability service outlet staff

- 9.4 FTE staff per outlet (average)

- Each consumer received 0.1 total staff hours in the year (average)

No. of volunteers in a typical week

- 32 FTE volunteers assisted in print disability service outlet operations

- 14.8% of all disability service outlet volunteers

- Represents 1.2% of paid staff hours in disability services

- 3.2 FTE volunteers per outlet (average)

- the highest across all disability service types

No. of consumers assisted in the year

- 29,836 used print disability services

- 18.0% of all consumers assisted across all disability service outlets

- 2,984 consumers per outlet (average)

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

1.5g Data summary of information services, 2007-08

No. of service outlets funded in the year

- 2 information service outlets

- 0.2% of all disability service outlets

State distribution of service outlets

- 1 in New South Wales

- 1 in the Australian Capital Territory

Geographic location of service outlets

- Both are located in major cities

Service outlet period of operation

- Both operated 7-8 hours a day

- Both operated 5 days a week

- Both operated the full 52 weeks in the year

No. of FTE paid staff in the reference week (Based on a 38-hour working week)

- 2 FTE paid staff worked in information services

- 0.03% of all disability service outlets

- 1.1 FTE staff per outlet (average)

No. of volunteers in a typical week

- 0.2 FTE volunteers supported information service outlet operations

No. of consumers assisted in the year

- 34,100 used information services

- 20.6% of all consumers assisted across all disability service outlets.

Chapter Two: History of the Disability Services Census

2.1 Overview of key developments

The Australian Government Disability Services Census was developed to provide comprehensive information on Australian Government funded specialist disability services, to assist in the planning, development and management of these services.

The first Disability Services Census was held in 1986. Prior to the introduction of the Disability Services Act 1986 (Cth) (DSA) on 5 June 1987, the legislative basis of disability services was the Handicapped Persons Assistance Act 1974 (Cth) (HPAA). On 4 September 1986 a census of all disability services funded under the HPAA was undertaken in preparation for the transition of these services to meet the requirements of the new legislation. Prior to the Census, the Department of Community Services and Health’s (DCSH) understanding of its disability services and consumers was limited for planning and administrative purposes. The Census of Disability Services report released in September 1988 presents a comprehensive statistical compendium on disability service operations, including staffing and financial matters, and consumer characteristics for each disability service type funded under the HPAA (DCSH 1988).

The next Disability Services Census was conducted some five years later in 1991. The resultant report provided summary statistics and commentary on all disability services funded under sections 10 and 13 of the DSA. The report’s coverage of disability service operations and consumer characteristics for each disability service type was consistent with the data presented in respect of the 1986 Census (Department of Health, Housing and Community Services, 1991).

Between 1991 and 1997, the Disability Services Census was conducted on a biennial basis. From 1998, the Census has been conducted on an annual basis. Between 1991 and 1999, Census information was collected on a ‘snapshot day’ or the day in the year the Census was conducted. From 2000, full financial year data has been collected.

A decision at the April 1993 meeting of the Working Party to the Review of Funding Arrangements for the Disability Services Program instigated a review of the 1991 Disability Services Census. As a result of this review, pilot testing was conducted in July 1993 to improve the Census collection. The resultant report was more comprehensive than its predecessor (Department of Human Services and Health 1994).

The 1995 Disability Services Census held on 18 October 1995 signified the first year in which the Census collection formed part of the first Commonwealth State Disability Agreement Minimum Dataset (CSDA MDS) conducted under the auspices of the heads of Australian, state and territory government disability services and coordinated by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). The CSTDA National Minimum Dataset (CSTDA NMDS) refers to the redeveloped ongoing collection, which was fully implemented nationally in October 2002. The change in the collection’s name stems from the negotiations of the third CSTDA (AIHW 2003).

The CSTDA NMDS is both a set of nationally significant data items that are collected in all jurisdictions for national reporting on CSTDA service provision and an agreed method of collection and transmission (AIHW 2003). The purpose of the CSTDA NMDS is to enable the annual collation of nationally comparable data on CSTDA funded services and to obtain reliable and consistent data on the type and location of these services, and an understanding of the people who use those services (FaCS 1999).

In 1996, outlet based funding and administration was introduced, where disability services were split according to activity and location and reclassified as separate entities known as outlets (FaCS 1998).

While the 1997 Census report remained relatively unchanged compared with the 1995 Census report, it signified the first year in which the Department of Family and Community Services (FaCS) became responsible for the Disability Services Census. The Census was held on 24 September 1997 (FaCS 1998). Since then, the Department has continued to have overall responsibility for the Disability Services Census.

A new feature of the 1998 Disability Services Census was the Accessibility Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA) to classify accessibility/remoteness. The ARIA classification includes Highly Accessible, Accessible, Moderately Accessible, Remote and Very Remote. The ARIA classification replaced the Rural and Remote Area (RARA) Index (FaCS 1999). In 2005, the Australian Standard Geographical Classification (ASGC) Remoteness Areas classification replaced the ARIA classification to align with AIHW’s reporting on CSTDA service provision. The ASGC Remoteness Areas classification includes Major Cities, Inner Regional Areas; Outer Regional Areas, Remote Areas and Very Remote Areas. This index offers a greater level of precision in its measurement of accessibility/ remoteness than the ARIA methodology, particularly in the more remote areas (AIHW 2004).

The 2000 Census report included two major data additions. Full financial year data on consumers accessing specialist disability employment assistance was collected for the first time, as was information on respite services (FaCS 2002). These data have been reported in subsequent Census reports.

The Machinery of Government (MoG) changes of December 2004 resulted in changes to the management of specialist disability employment assistance and subsequently to the way information on these services was presented in the 2005 census report. The MoG changes resulted in the transfer of responsibility for open employment services to the Department of Employment and Workplace Relations (DEWR) and the cessation of dual employment services as a separate disability employment service type, which provided both streams of specialist disability employment assistance. Responsibility for supported employment services stayed with FaCS. The 2005 Census report subsequently provided information on open and supported employment services only (FaCS 2006).

The 2006 Disability Services Census process reflected a significant departure from previous years with DEWR taking responsibility for the collection of open employment services data in line with the 2004 MoG changes (Department of Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs 2007).1 Two data sources were used for the 2006 Census collection. In addition to collecting information directly from disability service providers, FaHCSIA and DEWR also used administrative data to reduce the workload on service providers at census time.

The separate collection of open and supported employment services data continued for the 2007 Disability Services Census. To further streamline the data collection, the data provided by DEEWR2 included all data items in the CSTDA NMDS, but did not include the more detailed information on the employment characteristics of open employment service consumers collected in previous Censuses, that being the consumer’s phase and basis of employment, hours of employment, wages and industrial relations arrangements.

The structure of the 2007 Census report reflects the divergence in the Disability Services Census collection by FaHCSIA3 and DEEWR. The 2007 Census report includes information on consumers of disability employment services not provided in previous census reports. This report includes for the first time information on ‘severity of disability’, the ‘transport needs of supported employment service consumers’ and a special chapter describing changes in the profile of disability employment service consumers over time. Greater attention has also been given to the employment outcomes of equity groups and primary disability consumer groups.

The 2008 Census report mirrored the structure of the 2007 Census report – there were no changes.

- Following MoG changes in January 2006, FaCS was renamed the Department of Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaCSIA) to reflect the merger with the Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination (OIPC).

- Following MoG changes in December 2007, DEWR was renamed the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) to reflect some changes in functions.

- Following MoG changes in December 2007, FaCSIA was renamed the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) to reflect some changes in functions.

Chapter Three: Disability service outlet profile

- 3.1 Introduction

- 3.2 Description of disability service types

- 3.3 Number of disability service outlets

- 3.4 State distribution of disability service outlets

- 3.5 Geographic location of disability service outlets

- 3.6 Period of operation

- 3.7 National staff profile

- 3.8 Number of consumers assisted

3.1 Introduction

This chapter provides a profile of the operations of Australian Government funded CSTDA services in 2007-08. The information presented relates to the number of disability service outlets, service type provided, location of the service outlet, number of hours worked by staff, number of paid staff and volunteers, times of operation and the number of consumers assisted.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

3.2 Description of disability service types

Below is a description of the types of specialist disability services funded by the Australian Government under the CSTDA:

- Advocacy services assist people with disability to overcome barriers that impact on their daily life and their ability to participate in the community. Service provision focuses on six different models of advocacy: individual, citizen, family, legal, systemic, self-advocacy. The adoption of a range of models enables advocacy services to deliver flexible and responsive services to meet the needs of people with a disability.

- Disability employment services provide specialist employment assistance to people with a disability to assist them to obtain and retain employment. There are two types of disability employment services, open and supported. Open employment services assist job seekers with disability to obtain and retain employment in the open labour market. Supported employment services provide ongoing on-the-job employment support within a commercial enterprise.

- Information services facilitate access to information for people with a disability, their families, carers and professionals, and includes services to provide the information necessary to enable people with a disability to live full lives within their communities. This includes captioning of all elements of media entertainment (e.g. television, DVDs, cinema) for the deaf and/or hearing impaired.

- Print disability services produce alternative formats of communication for those who, by reason of their disability, are unable to read, hold or manipulate printed material. These alternative formats include braille, large print, audio recordings, computer discs and electronic text. These materials are delivered mainly through the Postal Concessions for the Blind program, a program funded outside the CSTDA.

- Respite services provide short term and time limited breaks for families and informal carers to assist in supporting and maintaining the primary care giving relationship, while providing a positive experience for the person with the disability.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

3.3 Number of disability service outlets

In 2007-08, the Australian Government funded a total of 1,201 disability service outlets nationally. Disability employment services accounted for the vast majority of disability service outlets, some 89.5% (1,075). Of these, 662 (55.1%) were open employment service outlets and 413 (34.4%) supported employment service outlets. Of the remaining 126 disability service outlets, 68 (5.7%) provided advocacy services, 46 (3.8%) respite services, 10 (0.8%) print disability services and two (0.2%) information services. Figure 3.1 shows the breakdown of disability service outlets by service type.

Figure 3.1: Disability service outlets, by service type, 2007-08

(a) Includes Targeted employment

Overall, there were nine less disability service outlets operating in 2007-08 than there were in 2006-07, down from 1,210.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

3.4 State distribution of disability service outlets

3.4.1 State distribution of disability service outlets across Australia

The state distribution of disability service outlets across Australia in 2007-08 is shown in Table 3.1. Importantly, the pattern is broadly consistent with the state breakdown of the general Australian population (ABS 2007a).

3.4.2 State distribution of disability service outlet types across Australia

Figure 3.2 shows the state distribution of disability service outlet types across Australia in 2007-08. Disability service outlets providing open employment, supported employment, advocacy and respite services operated in all states.

Based on the state distribution of all disability service outlets across Australia:

- the distribution of disability employment service outlets is broadly consistent with the national profile. The highest proportion of supported and open employment service outlets were located in New South Wales (37.8% and 34.6%, respectively), followed by Victoria (24.5% and 22.5%), Queensland (12.1% and 20.2%) and South Australia (10.4% and 10.6%).

- higher percentages of disability service outlets providing advocacy services were located in the following states: Victoria (30.9%), New South Wales (23.5%), Western Australia (13.2%), and Queensland (11.8%);

- higher percentages of disability service outlets providing respite services were located in the following states: New South Wales (30.4%), Western Australia (17.4%), Victoria (15.2%), Queensland (13.0%); and

- disability service outlets providing print disability services were located in each state except the Northern Territory.

Figure 3.2: State distribution of disability service outlet types across Australia, 2007-08

(a) Includes Targeted employment

(b) Includes Open & Supported employment

3.4.3 Disability service outlet type within each state

As shown in Table 3.2, disability employment service outlets were the most common disability service outlet type in all states in 2007-08. Overall, New South Wales had the most disability employment service outlets (385), as well as the most respite service outlets (14) and print disability service outlets (2). Victoria had the highest number of advocacy service outlets (21). The two information service outlets which provided a nationwide service were located in New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory.

As shown in Table 3.3, Queensland and New South Wales had the highest percentage of disability employment service outlets in 2007-08, with 92.5% and 92.1% respectively. The lower representation of these services in the Australian Capital Territory (78.3%) and the Northern Territory (70.0%) is influenced by the presence of other disability service types in those states.

For instance:

- the Northern Territory had the highest percentage of disability service outlets providing advocacy services (15.0%) and respite services (15.0%), compared with the national average of 5.7% and 3.8% respectively; and

- the Australian Capital Territory had a higher than average percentage of advocacy service outlets (8.7%) and one of the two information service outlets, which together accounted for 13.0% of all its disability service outlets.

Queensland had the highest percentage of open employment service outlets (67.3%), compared with the national average of 55.1%. The Australian Capital Territory and Tasmania had the highest percentage of supported employment service outlets (39.1% and 38.5% respectively), compared with the national average of 34.4%.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

3.5 Geographic location of disability service outlets

3.5.1 Geographic distribution of disability service outlets

Of the 1,201 disability service outlets that operated across Australia in 2007-08, the majority were located in major cities, some 56.9% (675). Based on the major city/non-major city breakdown of the general Australian population, there was a good balance of disability service outlets located in regional and remote areas. A total of 477 (40.2%) disability service outlets were located in regional areas, with 26.2% (311) in inner regional areas and 14.0% (166) in outer regional areas. Remote and very remote areas accounted for 2.9% (35) of all disability service outlets.

Note: Locational information is derived from postcode based data. As a result of 14 disability service outlets not providing their postcode they have been excluded from being mapped in the following relevant figures and tables.

Figure 3.3 shows the distribution of disability service outlets by geographic location.

Figure 3.3: Disability service outlets, by geographic location, 2007-08

Note: Excludes 14 unmapped disability service

3.5.2 Geographic distribution of disability service outlet types

The number of disability service outlets by disability service outlet type and geographic location in 2007-08 is shown in Table 3.4. Disability service outlets providing open employment, supported employment, advocacy and respite services operated in all geographic locations. Notably, disability employment services were the most common disability service type across all geographic locations.

As shown in Figure 3.4, a high proportion of disability service types were concentrated in major cities. That said, based on the major city/non-major city breakdown of the general Australian population, there was a good balance of disability employment service outlets located in and outside major cities. A similar pattern was seen for both open and supported employment service outlets. Importantly, 44.2% (471) of disability employment service outlets were located outside major cities, with 44.7% (294) open employment service outlets and 43.3% (177) of supported employment service outlets.

Figure 3.4: Percentage of disability service type outlet, by geographic location, 2007-08

(a) Includes Targeted employment

(b) Includes Open & Supported employment

Note: Excludes 14 disability service outlets which are not mapped

Advocacy services, however, were not as well represented outside major cities, accounting for 29.9% (20) of all such service outlets. Respite services had the highest representation of disability service outlets located outside major cities, 47.6% (20).

Finally, the geographic location of print disability and information services, which are located in major cities, is not critical to their overall effectiveness in delivering a quality service to people with a disability. The service delivery method adopted by these services – telecommunications and postage – means that the needs of their target groups can be easily met on a state or nationwide basis.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

3.6 Period of operation

Of the 1,201 disability service outlets that operated across Australia in 2007-08, the vast majority operated 7-8 hours a day (76.3%), five days a week (80.2%), for 48 or more weeks in the year (92.4%), with 50.0% (601) operating the full 52 weeks.

3.6.1 Hours per day

As shown in Figure 3.5, the vast majority of disability service outlets operated 7-8 hours a day in 2007-08, some 76.3% (916). A further 43 (3.6%) disability service outlets operated fewer than seven hours a day and 124 (10.3%) operated between eight and 23 hours a day, with 19 (1.6%) operating 24 hours a day. A small number (29) of disability service outlets overall had no regular pattern of daily operation. In addition, 69 (5.7%) disability service outlets did not provide hours of daily operation data.

Figure 3.5: Disability service outlets, by number of hours operating per day, 2007-08

Table 3.5 shows the breakdown of the number of hours operating per day for each disability service outlet type in 2007-08. The most common number of operating hours for all disability service outlet types was 7-8 hours a day. Of the 19 disability service outlets operating for 24 hours a day 18 were respite services and the other was open employment. Of the 30 outlets with no regular pattern of operating hours per day 28 were open employment services and 2 were respite services. Some of these open employment service outlets provided an outreach service and others provided an irregular on-call service outside of their usual operating hours.

3.6.2 Days per week

As shown in Table 3.6, the vast majority, some 80.2% (963) of disability service outlets operated five days a week in 2007-08. A further 73 (6.1%) disability service outlets operated less than five days a week and 66 (5.5%) operated six or seven days a week, with most of these (46) operating seven days a week. Overall a small number (31) of disability service outlets overall had no regular pattern of weekly operation. There were an additional 68 disability service outlets which did not provide weeks of operation data.

Table 3.7 shows the breakdown of the number of operating days per week for each disability service outlet type in 2007-08. Respite services were more likely than any other disability services type to operate seven days a week, accounting for 39.1% (18) of all disability service outlets to have operated these days. Twenty seven of the 31 disability service outlets with no regular pattern of operating days per week were providing open employment services.

Figure 3.6 shows the breakdown of the operating days per week for each disability service outlet type in 2007-08.

Figure 3.6: Disability service outlet type, by operating days per week, 2007-08

(a) Includes Targeted employment

(b) Includes Open & Supported employment

3.6.3 Weeks per year

As shown in Table 3.8, 92.4% (1,110) of disability service outlets operated 48 or more weeks in 2007-08, with 50.0% (601) operated the full 52 weeks, and 42.4% (509) operated 48-51 weeks in the year. A small number of disability service outlets (44) operated for fewer than 48 weeks in the year. Only 11 disability service outlets had no regular pattern of weeks of operation in the year, while 36 disability service outlets did not provide weeks of operation data.

Figure 3.7 shows the breakdown of the operating weeks for each disability service outlet type in 2007-08.

Figure 3.7: Disability service outlet type, by operating weeks in 2007-08

(a) Includes Targeted employment

(b) Includes Open & Supported employment

Of those disability service outlets that operated for 52 weeks per year, the highest proportion by disability service type were disability information (100%), and respite services - 45 (97.8%) of the 46 outlets.

Sixty per cent of print disability outlets reported operating 48-51 weeks in the year, with 42.4% supported employment, 44.9% open employment and 45.6% advocacy services reported operating for the same period of time.

[ Return to Top Return to Section ]

3.7 National staff profile

3.7.1 Hours worked by paid staff

In 2007-08, a total of 287,864 paid staff hours in the reference week were spent on disability service outlet operations. There were 54,824 (16.0%) less paid staff hours in the reference week spent on disability service outlet operations in 2007-08 than there were in 2006-07, down from 342,688.

Full-time equivalent (FTE) paid staff

Based on a 38-hour working week, a total of 7,575 FTE paid staff worked in disability service outlets across Australia in 2007-08. This equates to an average of 6.31 FTE paid staff in each disability service outlet. There were 1,443 (16.0%) less FTE paid staff working in disability service outlets in 2007-08 than there were in 2006- 07, down from 9,018.

Figure 3.8 shows the breakdown of FTE paid staff for each disability service outlet type in 2007-08.

Figure 3.8: Disability service outlet type, by FTE paid staff, 2007-08

(a) Includes Open & Supported employment

(b) Includes Targeted employment

Note: FTE paid staff have been rounded to the nearest whole number

Most FTE paid staff (3,712) worked in open employment services and (3,436) supported employment services (49.0% and 45.4% respectively). A further 180 (2.4%) FTE paid staff worked in respite services, 152 (2.0%) in advocacy services, 94 (1.2%) in print disability services, and 2 (0.0%) in information services.

3.7.2 Role of paid staff – direct and indirect support staff

The role of paid staff in disability service outlets is measured in terms of the provision of direct and indirect staff support:

- Direct support staff – staff that have direct contact with consumers in a support role. This includes coordinators, case workers and other staff who spend a major portion of their time in direct consumer contact.

- Indirect support staff – staff who have no, or only minimal, direct contact with consumers e.g. management staff, administrative staff, training personnel, etc.

A national breakdown of staff working in direct and indirect staff support roles in 2007-08 is not possible as this information was not collected in respect of open employment services. Of the data that is available, the ratio of direct to indirect support staff in disability service outlets was 2.1:1.