Pension Review Report

Table of Contents

- Abbreviations and acronyms

- Preface

- Summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Context and challenges

- 3. Adequacy

- 4. Indexation

- 5. Payment design and administration

- 6. Concessions and services

- 7. Sustainability and targeting

- Appendix A: Number of pensioners

- Appendix B: Pension payments as at 1 January 2009

- Appendix C: Supplementary entitlements available in the income support system, January 2009

- Appendix D: One-off lump-sum payments provhrefed since 2004–05

- Appendix E: Superannuation modelling

- Appendix F: Data sources and notes

- References

- Tables and charts

Abbreviations and acronyms

- ABS

- Australian Bureau of Statistics

- AETR

- average effective tax rate

- ALCI

- Analytical Living Cost Index

- COAG

- Council of Australian Governments

- CPI

- Consumer Price Index

- CSHC

- Commonwealth Seniors Health Card

- DVA

- Department of Veterans’ Affairs

- EMTR

- effective marginal tax rate

- FaHCSIA

- Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs

- GDP

- gross domestic product

- GST

- goods and services tax

- HILDA

- Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey

- MTAWE

- Male Total Average Weekly Earnings

- OECD

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

Preface

The Pension Review was commissioned by the Hon. Jenny Macklin MP, Minister for Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, to investigate measures to strengthen the financial security of seniors, carers and people with disability.

This report presents the Review’s findings, both in relation to its terms of reference and to the sustainability of the pension system and its role in the broader retirement income system.

The report is the culmination of nine months of research, analysis and consultation, which explored issues facing pensioners in terms of their financial security and wellbeing, and identified priority areas for pension reform. The report draws on a significant body of internal and external analysis, including technical research and modelling, and on feedback from the Review’s extensive consultation process.

A report of this breadth and quality is only possible because of the contributions of a number of people. While many individuals have contributed to the development of the report, I would particularly like to acknowledge the hard work of the talented and dedicated staff in the Pension Review Taskforce and would like to thank the following people:

- Robyn McKay, Nick Hartland, Andrew Whitecross and Ben Wallace for their leadership of the Taskforce and contributions to policy analysis and the development of the report.

- Rob Bray, Wayne Jackson, Robyn Oswald, Leonie Corver, Cathy Thebridge, Paul Miller, Jenny Thompson, Kyle Mitchell, Paul Martin, Andrew Wojciechowski, Peggy Hausknecht, Andrew Sinstead-Reid, Michelle Girvan and Steven Sue for their contributions to the analysis and research informing the Review, and for their work on drafting and editing the report.

- Fiona Sawyers, Lauren Nelson, Rose Nightingale, Joanne Harrison, Nikki Ross and Rachel Gibson for their contributions to the coordination of the Review’s consultation process and the production of the report, and for their work in supporting the Review’s governance mechanisms.

The Australia’s Future Tax System Review Panel, of which I am a member, also assisted the Taskforce to explore the interactions between the pension system and the broader retirement income system. I would like to thank my other panel members, Ken Henry AC, John Piggott, Heather Ridout and Greg Smith, for their time and expertise.

I would also like to acknowledge the contribution of members of the Review’s Reference Group, comprising Bruce Bonyhady, Ross Clare, Charmaine Crowe, Val French AM, Rhonda Galbally AO, Marion Gaynor, Bob Gregory AO, Lorna Hallahan, Joan Hughes, Gregor Macfie, Michael O’Neill, Patricia Reeve and Peter Whiteford. The Reference Group’s knowledge and experience were important in helping me clarify issues and identify priorities for reform. While the Reference Group’s input was valuable in helping shape and influence my thinking, the findings in the report are mine and should not be attributed to the Reference Group or any of its members.

Finally, I would like to thank the more than 2,000 Australian pensioners who contributed to the review through their submissions and participation in public forums and focus groups. The views and experiences of those pensioners who provided direct input through the consultations, helped shape and deepen our understanding of the issues central to the Review.

Jeff Harmer

27 February 2009

Summary

On 15 May 2008 the Minister for Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, the Hon. Jenny Macklin MP, asked the Secretary of her department, Dr Jeff Harmer, to lead a review into measures to strengthen the financial security of seniors, carers and people with disability.

The Review considers that the basic structure of Australia’s pension system, with its focus on poverty alleviation, indexation to community living standards and prices, and means testing, is sound. However it faces challenges in both the short and long term and reforms are needed:

- Pension rates do not fully recognise the costs faced by single pensioners living alone and the approach of paying ad hoc bonuses does not provide financial security. Additionally many pensioners who rent privately have high costs and poor outcomes.

- Indexation arrangements for pensions need to more transparently link pensions to community living standards and better respond to the price changes experienced by pensioners.

- Complexity needs to be reduced as it can undermine the financial security of pensioners, and inhibits the flexible delivery of payments.

- Services are an essential complement to the pension system and can respond to the diversity of needs in ways an income support system cannot. However, they need considerable review and reform to more effectively and sustainably perform this role.

- Workforce participation by pensioners over Age Pension age should be better supported while a stronger participation focus is needed for those of working age.

- In the face of demographic change long term sustainability is critical. The situation of pensioners with low to moderate reliance on the pension is different to those who are wholly reliant on the pension, and there is scope for targeting any increases to those who need it.

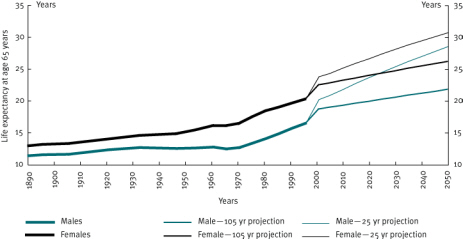

- An increase in the Age Pension age needs to be considered as a response to the rapid increases in the life expectancy of Australians and the growing duration of retirement.

The Pension Review

The Pension Review is the first opportunity since the Social Security Review (1986–88) for a comprehensive review of pension payments.

The Review has developed 30 findings across five major areas:

- the adequacy of the rate of the pension

- indexation arrangements for pensions

- the design and delivery of pension payments

- the concessions and services that support the pension system

- the targeting and long-term sustainability of the pension system.

The reform directions identified by the Review would involve a very substantial investment in the pension system by the government. The benefit of this would be a pension system that gives financial security to seniors, carers and people with disability, has greater integrity and is more sustainable.

In making its findings, the Review acknowledges the contribution made to its work by Australia’s pensioners. Over 2,000 pensioners, in public forums and written submissions, shared with the Review what the pension system means for them. The consultations showed that pensioners and the community have many strong views on the pension system and want to see these addressed.

However, the Review is aware that its findings will not meet all of the expectations that were expressed to it. Some of the proposals made in the consultations essentially sought to transform Australia’s pension system from one focused on providing basic income support for those who are most at risk of falling below an acceptable standard of living, to a social insurance style scheme akin to the systems that operate in a number of other OECD countries, or as a universal payment. This would have major structural, equity and budgetary implications.

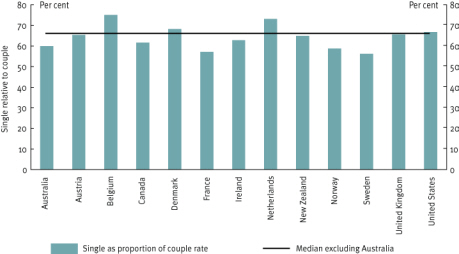

Compared with many other OECD countries, Australia’s income support system is targeted and efficient, and is relatively better placed to deal with demographic change. This is primarily because Australia’s focus on providing comprehensive, although conditional, basic income support does not expose the government and taxpayers to the financial risks of many of the social insurance style schemes adopted by other OECD countries. In many cases these social insurance style schemes are not sustainable in their current form and governments in these countries have been scaling back the benefits provided to current and future retirees.

The Pension Review was conducted during a period of potentially profound economic change. Consultations commenced in August 2008 following a long period of strong economic growth and in the shorter-term, rising inflation. The Review’s public forums and submission processes were winding up just as the impact of the global financial crisis emerged in late September and early October. The global financial crisis has underlined for the Review the importance of the sustainability of reform directions over the short and medium term.

In addition, government decisions on the rate and structure of the pension cannot be considered in isolation from the impact of demographic change. This is expected to increase pension expenditure by 1.9 per cent of gross domestic product by the middle of the century and increase spending on health and other services even more strongly. The ageing of the population also means that the cost of any current change in the pension rate compounds over time. Treasury modelling indicates, in the absence of other policy changes such as tightened targeting over time, that the cost of a given pension increase today will double as a share of gross domestic product by 2050. Funding these increases will require reduced spending elsewhere, increased taxes, or a combination of both.

These structural considerations and longer-term challenges shaped the Review’s approach of maintaining the basic structure of Australia’s pension system, building on its strength of focusing on those with the highest needs, and improving its sustainability.

Adequacy

The central question for the Review was the level at which the full rate of pension should be set.

The Review’s approach to this question was to test whether current rates of pension are providing a basic acceptable standard of living, accounting for prevailing community standards. The Review considered that the full rate of pension should provide a basic acceptable standard of living for those who are wholly reliant on it, often for extended periods, without any assumptions about access to private income or assets. In adopting this approach, the Review notes that while the question of adequacy can be conceived of in both absolute and relative terms, ultimately it needs to be answered in the context of contemporary society, and the living standards of others.

The Review examined a range of different measures of adequacy and outcomes to consider both the adequacy of pension payments and the relativities between pensioners. In doing so, the Review observed that no single measure or benchmark could be used to determine whether or not the pension was adequate, but rather a judgement needed to be made across a range of measures.

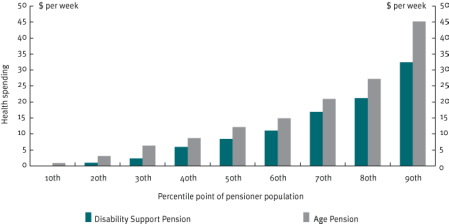

An initial question for the Review was how to respond to a variety of pressures faced by some pensioners from health and disability costs. The Review thought that the variation in these needs and costs are most effectively addressed through services. This is considered further in the Review’s findings on services and concessions. Reflecting this, the Review found that the pension should be paid at the same rate for those who are retired, or not currently expected to work because of their significant disability or caring responsibilities.

Finding 1: The Review finds that the Age Pension, Disability Support Pension and Carer Payment should be paid at the same basic rate.

Finding 2: The Review finds that the specific costs associated with health and disability are best responded to by targeted services rather than generalised differences in base rates of payments or financial supplements. (Section 3.4.3)

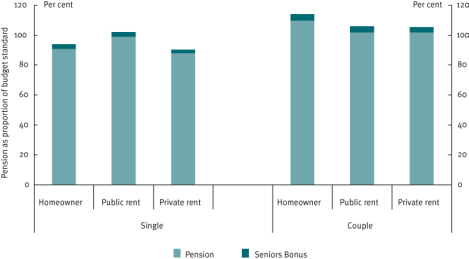

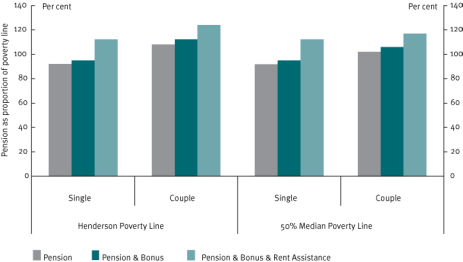

In relation to whether current rates of pension are providing a basic acceptable standard of living for all pensioners, the Review considered that the evidence showed that where a pensioner couple lived in their own house or rented from a public housing authority, and did not face unusually high costs of health or disability, the total package of assistance that they currently receive, including the value of the Seniors Bonus, was appropriate.

The Review, however, considered that the current relativities between single and couple payment rates do not take into sufficient account the costs faced by single pensioners who live by themselves, and the relativities should therefore be increased.

A central policy question in implementing reform to these relativities was whether the current two-tier structure of paying single pensioners and pensioner couples different rates should continue, or whether a three-tier structure (single pensioners living alone, single pensioners who live with others and pensioner couples) should be used. There are good reasons for proceeding in either direction.

Finding 3: The Review finds that, on the basis of its analysis of the outcomes achieved by pensioners, evidence provided in the consultations and its analysis of relative needs, the relativity of the rate of pension for single people living by themselves to that of couples is too low.

Finding 4: The Review finds that the case for a change in the relativity of the rate of pension for single pensioners living with others is less compelling. Such pensioners most frequently live with other relatives in owner-occupied housing and have outcomes more akin to couple pensioners than to other single pensioners. This suggests existing relativities are broadly adequate for these pensioners. However, the Review recognises that adding a third level of pension rate may introduce additional complexity.

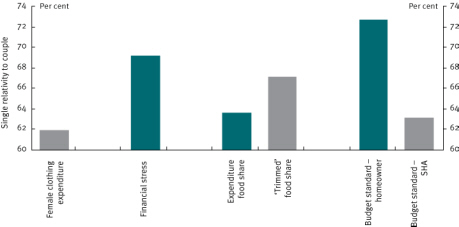

Finding 5: The Review finds that a relativity in the range of 64 to 67 per cent across the package of support would be more appropriate than the current relativity. Adopting a relativity towards the upper end of this scale would appear to be reasonable if a three-tier approach were to be adopted. Under a two-tier approach, where the same relativity would be applied to single pensioners living alone and those living with others, a relativity at the lower end of this scale would more adequately reflect the average needs across both these groups. (Section 3.4.4)

Finding 6: The Review finds that, taking into account the totality of the package of the current pension base rates, supplements and the value of the Seniors Bonus, the rate of pension paid to couples appears to be adequate for those pensioners living in their own homes or public rental housing, and without unusually high costs of health or disability. (Section 3.4.5)

An additional group for whom the current rates of total assistance do not appear to be providing a basic acceptable standard of living are some pensioners who do not own their own home, and rent privately. The poorer outcomes for these pensioners were both a result of the high cost of rent and other difficulties, including the security of their housing arrangements. Each of these dimensions need to be addressed.

Finding 7: The Review finds that there is strong evidence that many pensioners in private rental housing face particularly high costs and have poor outcomes. Rent Assistance and social housing have complementary roles to play in addressing the financial security of these pensioners. The Review notes that the government has proposed an increased investment in social housing and considers that reforms to Rent Assistance would complement this. (Section 3.4.6)

Indexation

Effective indexation arrangements are essential to maintaining the capacity of income support payments to provide a basic acceptable standard of living over time, and therefore to provide pensioners with ongoing financial security. The Review noted that this question, as with the determination of the rate of pension, needs to consider both the absolute standard of living of pensioners and the relativity of this to the rest of the community.

While there are strong arguments for decisions on changes in the rate of pensions to be taken as deliberative decisions by government, the Review considers that automatic indexation provides greater security for pensioners and should be continued.

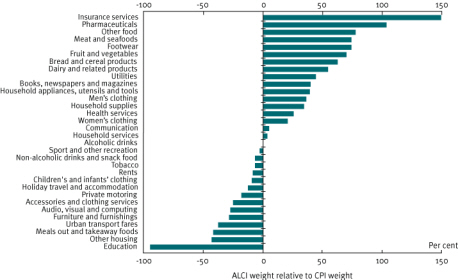

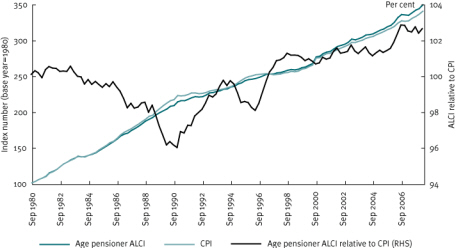

In considering how this can be best done, the Review analysed different approaches to price adjustment, including the Consumer Price Index and the Analytical Living Cost Indexes produced by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, and the wide range of different ways in which a community benchmark can be defined and measured. It also analysed the longer term relationship between indexation and sustainability in the light of changes in the population structure, especially the rising dependency ratio between the population aged over 65 years and the ‘working age’ population.

While supporting the continuation of the current two part indexation to prices and community living standards, the Review considered there should be a different emphasis on the roles of the two components, with benchmarking to changes in community living standards as the central long-term indexation factor for pensions.

Finding 8: The Review finds that automatic indexation of pensions and a two-part approach of benchmarking and indexation should continue. Benchmarking pensions relative to community standards should be the primary indexation factor, with indexation for changes in prices acting as a safety net over periods where price change would otherwise reduce the real value of the pension. (Section 4.4.2)

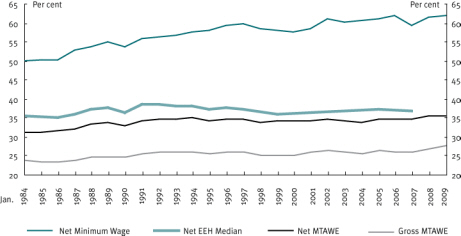

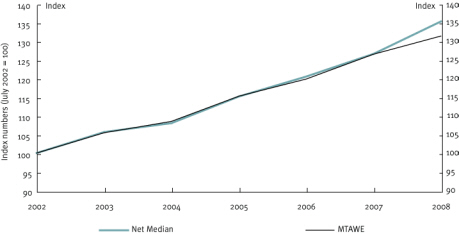

The Review considered that both the current measures used for indexation, the Consumer Price Index and Male Total Average Weekly Earnings have drawbacks that make them less than ideal measures to ensure the maintenance of an appropriate rate of pension over time.

Detailed analysis of the Consumer Price Index and other measures of price changes led the Review to conclude that an alternative measure of price change which is more fully responsive to specific changes in pensioners’ purchasing power would be appropriate.

The Review’s analysis also indicates that reforms are needed to the current approach of using Male Total Average Weekly Earnings to benchmark pensions to community living standards because of its lack of transparent relevance to the experience of the wider community. While there was no single measure ideally suited to this task, the Review considered that a measure based on the net income of a full-time worker was the most appropriate, in that it removed the distorting influence of part-time work and focused on the disposable, rather than pre-tax, income of people in the workforce.

Finding 9: The Review finds that pension indexation for price change would be better undertaken through an index that more specifically reflected cost of living changes for pensioners and other income support recipient households. (Section 4.4.3)

Finding 10: The Review finds that no single measure to benchmark the pension to community living standards is without limitations. However, the Review considers that a measure of the net income of an employee on median full-time earnings may be a more appropriate measure than the existing Male Total Average Weekly Earnings benchmark. (Section 4.4.4)

Indexation is however highly technical and the Review’s approach would involve some additional data collection and analysis as well as refinement of measurement frameworks. There is also the potential for interaction between the setting of the proposed benchmark and potential policy changes subsequent to the Australia’s Future Tax System Review. For these reasons the Review considered that implementation of reform may need to be staged.

Finding 11: The Review finds that, while reform to indexation and benchmarking is important to the financial security of pensioners, implementation may need to be phased in to account for policy developments that may arise out of the Australia’s Future Tax System Review and to allow for the development of appropriate mechanisms for benchmarking and indexation. (Section 4.4.4)

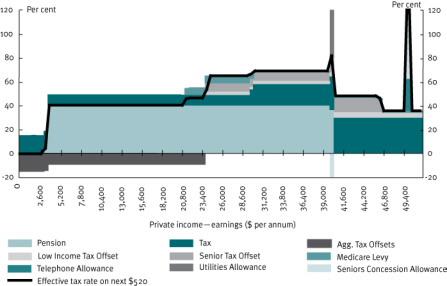

The Review also considered how other income support parameters, such as the means test free areas, should be adjusted. These parameters are usually indexed by the Consumer Price Index, and therefore increase less quickly than pension rates. This ‘fiscal drag’ has the potential to introduce unintended distortions into payment structures. The Review concluded that indexation arrangements that create distortions between different components of the payment systems should be avoided, and if they cannot, should be subject to regular review.

The Review’s findings in relation to payment design and administration, and targeting and sustainability particularly the findings on supplementary payments, Rent Assistance, and the treatment of earned income are designed, in part, to address the distortions currently within the pension system that have arisen because of the different indexation arrangements for different income support parameters.

Payment design and administration

The way that assistance is delivered and administered is important to the financial security and wellbeing of pensioners. Needlessly complex payment design and administration have the potential to:

- impose high transaction costs on pensioners

- generate poor outcomes for those who are not well placed to manage complexity

- make different elements of the system unintentionally work against each other

- generate consequences for other systems which need to interact with the income support system.

It was clear from the Review’s analysis that there is scope to reform the way in which the payments to pensioners are structured to improve flexibility and financial security for pensioners, to reduce complexity and improve program efficiency and effectiveness.

Initial considerations focussed on the components of the total assistance that are provided to pensioners, including the balance between regular and one-off lump-sum and supplementary payments.

The Review considered that one-off lump sum payments were not a particularly effective way of addressing the adequacy of the pension in the long term and their ad hoc provision failed to provide security to pensioners. It did, however, recognise that this type of payment may continue to have a role in some specific circumstances.

Finding 12: The Review finds that one-off lump-sum payments are not particularly effective mechanisms for addressing the adequacy of the pension because they do not provide ongoing financial certainty for pensioners.

Finding 13: The Review finds that one-off payments may have a role in circumstances where pensioners may not otherwise gain from specific budgetary or economic changes, such as from changes to taxation arrangements, to compensate for policy changes, or where a fiscal stimulus is desired. (Section 5.3.1)

With respect to the current system of supplementary payments, the Review considered that the payment of these as individual items, with the exception of Rent Assistance, was largely based in the history of the pension system and there was little justification for maintaining them as separate payments.

Simplification could be done in a number of ways, with the main choices being between integrating all payments into the base rate of pension or bringing these supplementary payments together into a single supplement. While integration into the base payment would bring the greatest simplicity into the pension system, a separate supplementary payment provides more scope for flexible structuring of payments.

Such flexibility could, for example, involve a pensioner having a choice of the timing of the payment of the supplement to reflect their own budget priorities and needs. This approach would provide a mechanism to respond to the diversity of views expressed in the consultations, where some pensioners strongly supported the payment of some portion of the pension as a lump sum to assist them in meeting capital and other expenditures and others preferred to manage on regular payments.

If a separate supplement were to be created the Review considered that it was important to ensure this did not undermine the relativities established in the base pension rates between singles and couples.

Finding 14: The Review finds that integrating supplementary payments (Pension GST Supplement, Pharmaceutical Allowance, Telephone Allowance and Utilities Allowance) into a single supplementary payment or absorbing them into the base rate of pension would simplify the structure of pensions. Integration with the base rate would maximise simplicity while a separate supplement would provide a platform for introducing flexibility around the frequency of the payment of a component of the total pension package.

Finding 15: The Review finds that, if paid separately, any supplementary payment should be paid to singles and couples in proportion to the rate of the base pension to ensure that the relative value of the pension package is maintained. (Section 5.3.2)

Finding 16: The Review finds that an integrated supplement would be an appropriate vehicle for delivering greater flexibility over the timing of payments and would permit pensioners to structure their receipt of income according to their budgetary priorities.

While caution should be exercised in applying a flexible approach to the base rate of pension an option of weekly payment cycles may be preferred by some pensioners. (Section 5.3.3)

Rent Assistance, the largest of the supplementary payments, plays an important role in assisting pensioners who rent in the private rental market and who often face high housing costs. The Review found that the effectiveness and the equity of the program had been reduced by the impact of ‘fiscal drag’ resulting from the way the program parameters had been indexed over time. The Review concluded that there was scope to improve the targeting of this payment so that it better met the needs of those who face the highest housing costs.

Finding 17: The Review finds that there would be merit in restructuring rent thresholds to target Rent Assistance to those who pay higher rents and addressing inequities that have arisen with the sharers rate of Rent Assistance. (Section 5.3.4)

From its examination of the Pension Bonus Scheme, the Review concluded that this program had been developed in different circumstances and was complex, inefficient and inflexible in promoting the continued employment of people of Age Pension age and that alternative mechanisms should be developed.

Finding 18: The Review finds that the Pension Bonus Scheme is not a particularly effective means of increasing workforce participation by older Australians and that this goal would be better pursued through the design of the pension means test to ensure that there are appropriate incentives for employment. (Section 5.3.5)

The current situation where a person above Age Pension age may be eligible for either the Age Pension, Disability Support Pension or Carer Payment was considered by the Review as a needless area of administrative complexity, both for individuals and Centrelink. It also had the potential to reduce the effectiveness of Disability Support Pension and Carer Payment as payments to persons of workforce age. To address this, the Review considered that initial action should be taken to harmonise the treatment of people of Age Pension age across all three payments, with a longer term view to structural change in the context of the Review’s findings on the role of working age pensions.

Finding 19: The Review finds that the current situation where a person above Age Pension age may be eligible for either the Age Pension, Disability Support Pension or Carer Payment is unnecessarily complex, and that the Age Pension should be the appropriate payment for people over Age Pension age. As a first step to achieving this, there should be consistency of treatment across pension payments for those of Age Pension age to remove incentives for payment swapping.

In the longer term, making the Age Pension the payment for people over Age Pension age would focus the Disability Support Pension and Carer Payment on their role as working-age payments, with workforce participation encouraged. (Section 5.3.6)

Concessions and services

Concessions and services play a critical role in the social protection system by responding to the high needs that some pensioners have due to health conditions and some types of disability. This was highlighted in the consultations. Issues about concessions and services were consistently raised throughout public forums, written submissions and focus groups, with a particular focus on the cost of health care, including medical and dental treatment and pharmaceutical expenses.

While the base rate of pension can address the ‘normal’ level of health and related service costs faced by most pensioners, where the level of need for these services is higher, this is no longer the case. Responding to this variation in the payment system is difficult because of the way in which needs vary considerably between individuals. As noted earlier, the Review does not favour responding to unusually high costs of health or disability through the payment system.

The two main issues addressed by the Review were the targeting and effectiveness of concessions and the reform of services, in particular for people with disability.

Overall the Review considered that the existing wide range of concessions were often poorly targeted and as a result, despite high levels of expenditure, concessions did not effectively complement the pension system by being responsive to the relative needs and circumstances of different pensioners, in particular those with greater needs. The existing structures and levels of concessions were seen as being difficult to sustain in the longer term.

As concession cards play a central role in the access to many concessions the reform of the targeting of these is a priority. Reform needs to be done in coordination with the states and territories.

Finding 20: The Review finds that the targeting of concession cards does not effectively complement the role of income support in addressing the needs of groups with high costs and that this needs to be addressed in consultation with the states and territories. (Section 6.5.2)

In the context of this work, the Review considered that the Commonwealth Seniors Health Card’s role of making health concessions available to people outside of the income support system, but who have similar levels of income to those who receive a payment, should be maintained.

The Review also considered that there is a case for aligning the definitions used in the Commonwealth Seniors Health Card income test with those used in the pension income test, to reduce complexity and the potential for inequitable outcomes.

Finding 21: The Review finds that, subject to more detailed considerations of the targeting of concessions, there is merit in maintaining the function of the Commonwealth Seniors Health Card in making health concessions available to people who are not eligible for the Age Pension, but have similar levels of income to age pensioners. Further, the Review considers that there would be a case for aligning the definitions in the income test for the Commonwealth Seniors Health Card with those of the pension income test. (Section 6.5.2)

In considering services, the Review noted the very significant reform agenda being developed under the auspices of the Council of Australian Governments, as well as the long-term funding and sustainability issues being addressed through the National Disability Strategy and the Disability Investment Group.

The Review considered these processes, which are directed at improving disability services and support, have the potential to contribute significantly to the outcomes of many pensioners with high needs, as well as their carers, and the Review was strongly supportive of the work that is being undertaken.

The Review’s analysis led to priorities for: a more integrated and person-oriented approach to service delivery; the exploration of new approaches to funding, including leveraging private contributions and more effective public and private provision; and ensuring a stronger labour market focus, both for people with disability and their carers.

These priorities also reflect the Review’s observation that the long-term sustainability of the services and support provided to people with disability, including sustaining the role of informal care, is as critical as the pension system itself, and contributes to its long-term sustainability.

Finding 22: The Review finds that the reforms to services and support being developed by the Disability Investment Group, and under the National Disability Strategy and the National Disability Agreement, in particular the development of a more person-centred approach that cuts across service boundaries and seeks to tailor a targeted package of support, are vital steps towards providing adequate support to those who have high and complex needs. (Section 6.5.3)

Finding 23: The Review finds that the development of new approaches to funding services and support for people with disability is important to the long-term sustainability of the system. In particular, the idea of a National Disability Insurance Scheme is worthy of further consideration. The Review notes that both the Council of Australian Governments and the Disability Investment Group are examining the long-term sustainability of the services system, and that the Australia’s Future Tax System Review Panel has noted that the funding of services is a significant issue and will consider how alternative approaches would fit into the structure of the overall tax-transfer system. (Section 6.5.4)

Finding 24: The Review finds that reviews of funding arrangements should take into account the need to ensure that people with disability and carers have better opportunities to establish and maintain links with the labour market and through that are able to contribute to their own retirement incomes. (Section 6.5.5)

Sustainability and targeting

The questions of the sustainability of the pension system and of the reform directions identified by the Review are critical to the long term financial security of pensioners and the ability of Australian society to support them. Central to this is how payments are targeted, both through program eligibility and related criteria and the operation of means testing. Because of the dual nature of means testing, which on one hand operates as the mechanism for targeting support to those who need it, and on the other can create disincentives for work and savings, careful balances need to be struck.

The Review considered whether the balance of means testing is right by reference to three principles:

- targeting pension assistance to those most in need

- ensuring that incentives remain for people to provide for themselves through savings or work

- ensuring within the pension system that people with similar levels of means and financial circumstances receive similar levels of income support.

Eligibility criteria for programs play both a direct gate keeping role, and more generally contribute to community norms. This is particularly the case with the Age Pension age, which helps to set retirement expectations.

Means testing and adequacy

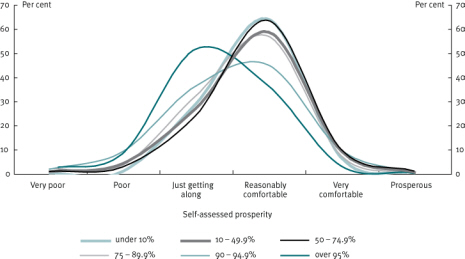

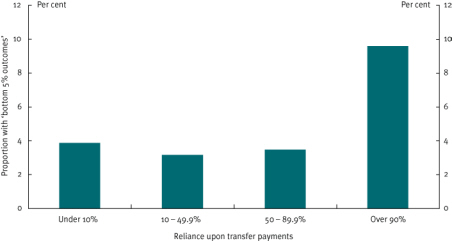

Complementing the Review’s considerations of the appropriate level of the rate of payment of the pension to those who are wholly reliant on it was the question of the appropriateness of the levels of pension payments to these with low to moderate reliance on income support.

The Review found, on the grounds of adequacy, that the means test is not generating inappropriate outcomes in terms of the level of payment made to pensioners who have lower levels of reliance on the pension as a source of income.

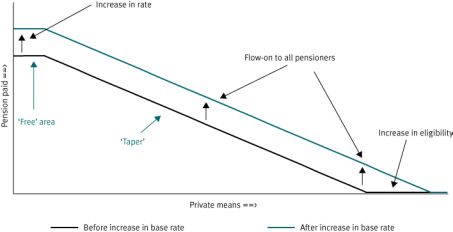

The Review considered, on this basis and given its findings on the rate of payment had been directed at addressing the adequacy of those wholly reliant on the pension, that there is no reason for any increase to flow on to those who have much less reliance on the pension. Therefore the Review saw scope for the means test to be tightened, so as to ensure effective targeting and reduce any inappropriate cost impact of addressing the needs it had identified.

Finding 25: The Review finds that there is no evidence that the means test as a whole is operating to provide an inadequate level of support to pensioners with low to moderate reliance on the pension.

Finding 26: The Review finds that, in the case of an increase in the pension rate to achieve an improvement in adequacy and financial security for those pensioners for whom the pension is the predominant source of income, there would be capacity to tighten income test settings to limit the flow-on of the increase to pensioners with low to moderate reliance on the pension. (Section 7.5.1)

Effectiveness and efficiency of means testing

The Review’s analysis of the operation of the means test, and on achieving a fair and sustainable balance in the pension system between the effective targeting of assistance and ensuring that there are incentives for people to participate in the labour market and to save and to support themselves, identified a more general need to improve the efficiency of means testing.

These matters are closely allied with wider long term questions that are being considered by the Australia’s Future Tax System Review. However, the Pension Review considered there was scope for more immediate action to address the assessment of earnings by pensioners of Age Pension age and the way some superannuation products are treated.

From the consultations, it is clear that the operation of the income test is seen by many age pensioners in particular as a barrier to participation. The Review considered it was important to address this, especially given the poor performance of the Pension Bonus Scheme and the importance of supporting participation by these pensioners. Many older Australians are seeking to better manage their transition from work to retirement and possess skills and experience which offer much to employers. Others simply wish to be able to enjoy a higher standard of living in their retirement and to work to enable this. The Review considered that the preferred mechanism to do this was to treat concessionally a moderate amount of earned income.

Finding 27: The Review finds that there is a case to provide more effective mechanisms to support age pensioners to maintain or take up paid work if they wish to do so. A concessional treatment of low to moderate levels of income from employment would better deal with the costs of work which are only partially offset in the current means test and be more effective than the current Pension Bonus Scheme. (Section 7.5.3)

Under the existing means test, superannuation, including the most common account-based products, is treated differently to other financial assets. This treatment is complex, distorts the pattern of pension payments, and favours these products over other investments. The Review considered that a more neutral approach should be taken.

Finding 28: The Review finds that a deeming approach for account-based superannuation products would remove the current distortion in the pattern of payment of pensions to pensioners with such income and assist in equalising the treatment of superannuation products and other financial assets. (Section 7.5.3)

Eligibility criteria for working age pensions

Improving the connections between pensioners on working age payments and employment is a high priority both for the sustainability of the pension system and to improve outcomes for pensioners. Australia has low levels of workforce participation in a number of groups of working age, including people with disability. The Review noted however this requires a different approach than that identified for age pensioners. In particular, pensions for those of working age have quite a different relationship to employment than the Age Pension. Working age payments are made conditionally on the basis of a person being unable to currently undertake substantial employment because of disability or caring. As such it is important that these pensions actively support people to participate to the extent their capacity permits, to develop this capacity and to be able to re-enter the workforce if their circumstances change.

The Review considered that it is important that this focus be better reflected in these programs to orient them towards actively building these pathways to employment.

Finding 29: The Review finds that the Carer Payment and Disability Support Pension should more actively address questions of workforce participation. This focus needs to be effectively integrated into initial eligibility, policies to promote participation while people are on the payments and in ensuring that, where they have the capacity to support themselves and are no longer eligible for the pension, they can successfully establish or re-establish themselves in the workforce. (Section 7.6.1)

Age Pension age

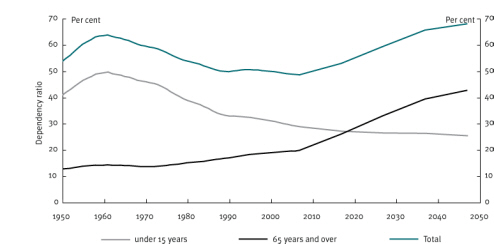

Demographic change is a major challenge to the pension system. As a result of the ageing population the ratio of people of working age to those aged 65 and over will more than halve from its current 5.0 to 2.4 by 2047. In addition there has been a marked shift in the level of workforce participation of many working age people, including early retirement. This has ramifications for both the tax base and spending.

In this context the Review considers that an increase in the Age Pension age needs to be seriously considered. An increase in the Age Pension age would partially redress the increasing dependency rate and concerns about a largely static workforce. Longer periods in employment would increase the time a person is able to contribute to national levels of production and the tax base. For industry, it would provide extended access to an experienced workforce.

For the retirement income system later retirement would reduce the span of time that people need to cover with their savings, including superannuation, and enable them to add to these savings to provide a higher living standard in retirement. It would also reduce demand on the Age Pension.

The Review considers that a moderate increase of some two to four years in the Age Pension age would be reasonable given the very strong increased life expectancy of Australians.

However, an increase in the Age Pension age represents a major cultural change and would require a substantial change in people’s expectations about their working lives and preparations for their retirement. It would therefore have to be introduced gradually, with changes commencing after the Age Pension age for women meets the age for men in 2014.

A change in the Age Pension age would also need to be accompanied by other policy changes. Because a very large proportion of people retire prior to the Age Pension age a change in the age itself will not necessarily result in higher levels of participation or lower levels of receipt of income support. Central to this could be to bring the preservation age for superannuation into alignment with the Age Pension age.

Finding 30: The Review finds that there is a case for a phased increase in the Age Pension age starting from 2014, when the Age Pension age for women will be the same as for men. Such a policy would improve retirement outcomes and support Australia’s capacity to address the impact of population ageing. It would reflect the strong increases in life expectancy the nation has experienced, which are expected to continue. Any reform would need to be part of a coordinated approach to retirement, including bringing the settings of the superannuation system into line with the Age Pension age. (Section 7.6.2)

Australia’s Future Tax System Review

The findings of this report need to be considered in the context of the broader work of the Australia’s Future Tax System Review, which is considering the tax structure needed to position Australia to deal with the social, economic and environmental challenges of the 21st century. Although the Panel overseeing the tax system review is due to report by the end of 2009, the government asked the Chair of the Review, Dr Ken Henry AC, to provide a report on the retirement income system by the end of March 2009. This request was to enable the government to consider the two reports together.

1. Introduction

1.1 Scope of review

On 15 May 2008 the Minister for Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, the Hon. Jenny Macklin MP, announced that the Secretary of her department, Dr Jeff Harmer, would lead a review into measures to strengthen the financial security of seniors, carers and people with disability. The investigation was to include a review of the Age Pension, Carer Payment and Disability Support Pension.

1.1.1 Terms of reference

The Minister asked Dr Harmer to report to the government on the outcomes of the Pension Review by 28 February 2009. The terms of reference directed the Review to consider:

- the appropriate levels of income support and allowances, including the base rate of the pension, with reference to the stated purpose of the payment

- the frequency of payments, including the efficacy of lump-sum versus ongoing support

- the structure and payment of concessions or other entitlements that would improve the financial circumstances and security of carers and older Australians.

The Pension Review has been undertaken in the context of the wider inquiry into Australia’s Future Tax System, which is considering the tax structure needed to position Australia to deal with the social, economic and environmental challenges of the 21st century. The terms of reference for the inquiry into Australia’s Future Tax System require it to consider ‘improvements to the tax and transfer payment system for individuals and working families, including those for retirees’. While the Panel overseeing the tax system review is due to report by the end of 2009, the government asked the Chair of the Review, Dr Ken Henry AC, to bring forward his report on the retirement income system to March 2009, to allow that report to be considered in conjunction with the Pension Review report.

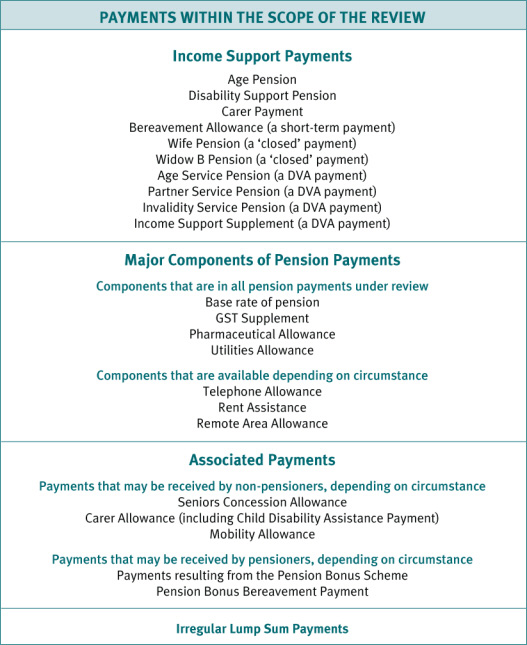

1.1.2 The Pension Review’s scope

The payments that are a focus of the Pension Review (the Age Pension, Carer Payment and Disability Support Pension and, as discussed in more detail in Section 5.1.1, certain Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) payments and a number of smaller and closed Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs payments are part of the broader income support and family assistance systems. Many of the issues considered in this report are also relevant to the wider system of pensions and allowances. However, the Age Pension, Carer Payment and Disability Support Pension are different in that the capacity of people on these payments to undertake full-time employment to support themselves is significantly curtailed. In addition, the community generally does not expect that people receiving these payments should be required to seek work to support themselves, because they:

- have already reached a specific age, or

- are undertaking a significant caring role that limits their availability for paid employment, or

- are unable to undertake significant employment, including part-time work, at least in the intermediate term, due to disability.

In recognition of the different capacities and expectations around workforce participation, the means test for pensions is more relaxed than that for allowances, where work is required. The pension means test is designed to provide incentives for some workforce participation for those who have the desire, capacity and opportunity to do so, but is not so concerned with the implicit effects of higher rates of payment and longer tapers, which allow people to combine part-rate pensions with income from part-time or casual work, but may reduce incentives for full-time employment. In addition, the structure and rate of the pension take into account the very long durations on payment of many pension recipients and the more limited opportunities some seniors and those with significant disability or ongoing caring responsibilities have for entering or re-entering the workforce.

One important difference between the pensions considered here is that, while eligibility for the Age Pension is based simply on age (and other criteria such as residency and means), eligibility for Carer Payment and Disability Support Pension is tested, on an ongoing basis, against the capacity of individuals to support themselves in the labour market. That is, the Disability Support Pension and Carer Payment are not paid on the basis of a person having a disability or caring responsibility per se, but rather because of the extent to which their disability or caring significantly inhibits their capacity for employment.

The Pension Review, reflecting both the terms of reference and the interrelationship between program components, took a comprehensive approach to the support available to people receiving the Age Pension, Carer Payment and Disability Support Pension. This support includes pension payments, supplementary payments and allowances, and concessions and services. The Review also considered targeting mechanisms, such as the ‘income test free’ areas and means test taper rates. All of these program components are intended to operate together to provide financial security and an appropriate level of income.

In its work it was clear to the Review that many features of the pension system have developed on an ad hoc basis or as pragmatic solutions to immediate problems. In this report, the Review has sought to identify underlying principles to guide its own considerations and future pension policy.

1.2 Program of work

The Pension Review provides the first opportunity since the Social Security Review (1986–88) for a comprehensive examination of pension payments. To support the development of this report, the Review has drawn extensively on internal and external analysis, including technical research, and has undertaken a wide ranging consultation process.

The Pension Review has progressed during a period of profound economic change. Consultations commenced in August 2008 following a period of rising inflation and strong economic growth. As the impact of the global financial crisis emerged in late September and early October, the public forums and submission process were winding up and the first round of focus groups was commencing. In October 2008, while the first round of focus groups was running, the Australian Government announced a $10.4 billion Economic Security Strategy to strengthen the Australian economy, which included a $4.8 billion down payment on long-term pension reform. In December 2008, the Australian Government announced additional support to pensioners to fully meet the expected overall increase in costs flowing from the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme. In February 2009, the Australian Government announced its $42 billion Nation Building and Jobs Plan, which included a major investment in social housing.

Chapter 2 of the report provides further details about the impact of the global financial crisis on pensioners and the pension system.

1.2.1 Background Paper

On 11 August 2008, the Pension Review Background Paper (the ‘Background Paper’) was released to inform the public debate about issues surrounding the pension system. The Background Paper included a detailed discussion about the key issues of consideration under each of the Review’s terms of reference. It also provided information on the economic and social context within which the pension system operates and detailed information about the current income support system, including the number of people on payments, payment rates and historical trends.

The Background Paper contained a significant amount of the initial research and analysis undertaken by the Review and should be seen as a companion to this report.

1.2.2 Consultation

The Review engaged in an extensive consultation process, involving a series of public forums, meetings with state and territory government officials, a call for written submissions and a series of small focus groups. The Review draws on material resulting from the consultation process throughout the report.

Public forums

Public forums were held during August and September 2008 to ensure that seniors, carers and people with disability, and the organisations that represent them, had the opportunity to provide direct input to the Review. A total of 485 people attended the forums, which were held in all capital cities as well as Newcastle, Rockhampton and Wangaratta. Forums were held in a town hall format. Participants also had the opportunity to provide written input through feedback forms.

Consultations with state and territory governments and others

Representatives from the Review met with officials from all state and territory governments to discuss the interactions between the Review and policy responsibilities of state and territory governments. These discussions focused on the Review’s third term of reference—the structure and payment of concessions and other entitlements—since state and territory governments are responsible for delivering a wide range of concessions and services to seniors, carers and people with disability.

Representatives from the Review also met with the National People with Disabilities and Carers Council; the Disability Investment Group; the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Family, Community, Housing and Youth; and the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Petitions.

Written submissions

Over 1,800 written submissions were received by the Review. The majority of submissions were from individuals, although some 130 submissions were received from organisations.

The Review has paid considerable attention to the issues raised in the submissions and the breadth of the concerns expressed. It has also analysed the frequency with which issues have been raised.

An important aspect of the analysis of the submissions is that it provided a more systematic insight into issues of concern for particular subgroups, such as people receiving different pension and related payments, singles and couples, and those living in different locations.

Focus groups

The Review commissioned Centrelink to run nine focus groups in October 2008 and three focus groups in January 2009, to further explore issues raised during the public consultation process. Issues covered in the focus groups included financial disadvantage, work incentives, concessions and services, and supplementary payments. Participants were randomly selected Age Pension, Carer Payment and Disability Support Pension recipients. The focus groups involved a mixture of group discussion, data collection and written responses.

The focus groups were also a useful mechanism to explore some of the specific issues raised in submissions.

1.2.3 Reference Group

In her statement of 15 May 2008, Minister Macklin advised that Dr Harmer would convene a Reference Group to ensure that the Pension Review reflected the views and aspirations of those most likely to be affected by any reforms. The Reference Group, which met for the first time on 29 July 2008, included representatives from seniors, carers, disability and general welfare groups, as well as members of academia. The Reference Group met six times between July 2008 and February 2009.

The Reference Group advised on the range of issues facing seniors, carers and people with disability, and on priorities for reform. The Reference Group also considered and provided feedback on much of the research and analysis undertaken by the Review.

1.2.4 Research and analysis

To inform the Review and support the development of the report, the Review engaged in a program of research and analysis. Much of this work fed into the Background Paper, which was released prior to the consultations. The Background Paper should be seen as a complementary volume to this report.

Much of the analysis for the Review was undertaken using existing research and analysis, such as Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) reports and the Australian Treasury’s Intergenerational Report 2007, and through analysis of existing administrative and survey data. In particular, the Review was informed by analysis of equivalence scales, financial hardship and indexation approaches; analysis of health expenditure data; and modelling of Superannuation Guarantee outcomes. The Review’s analysis also benefited from sharing of information and data from other Australian government departments, and from state and territory governments, and by drawing on material from the public consultations.

1.3 Report outline

Apart from Chapter 2, which considers the broad context of the Review, the chapters of the report are presented in a standard manner:

- overview and findings

- the terms of reference of the Review and a description of the issues under consideration in the chapter

- the input the Review received through consultations and submissions

- the analysis undertaken within the Review

- reform directions.

1.3.1 Context and challenges

While the terms of reference focus on the Age Pension, Carer Payment and Disability Support Pension, it was not possible for the Review to develop considered views on the operation of these payments under the terms of reference without considering their role in Australia’s broader social protection system.

Chapter 2 (Context and challenges) therefore provides an overview of Australia’s pension system and how it fits within the broader social protection system. The chapter also discusses demographic change and the ageing of the population, because these long-term trends will have a major impact on the Age Pension, Disability Support Pension and Carer Payment, and are therefore a crucial part of the context of the Review.

Chapter 2 then identifies five major challenges for the pension system that were central in providing a framework for the Review’s consideration of its terms of reference: the global financial crisis, sustainability, the management of risk in retirement, workforce participation and interactions with the broader tax-transfer system, and complexity.

1.3.2 Term of reference 1: Appropriate levels of income support

Chapter 3 (Adequacy) examines the central question of the level at which the full rate of pension should be set and identifies the priorities for reform of the Australian pension system. It considers the purpose of payments and the concept of adequacy given the diversity of individual needs and circumstances. It reviews a range of different measures of adequacy and outcomes, to consider both the adequacy of pension payments and the relativities between pensioners. It also considers the need for supplementary assistance for housing costs. The question of the appropriate level of income support for those pensioners with some private means is considered in Chapter 7 (Sustainability and targeting).

The maintenance of adequacy over time in light of changes in the cost of living and in community living standards is considered in Chapter 4 (Indexation). This chapter considers the way in which adjustments are made to the rate of the pension and other parameters of the pension system. It outlines the current indexation arrangements; discusses the merits of different approaches to price adjustment, including the Consumer Price Index and the Analytical Living Cost Indexes; and considers issues around indexation and sustainability. It also outlines the current benchmarking arrangements and discusses the relative merits of different benchmarking measures.

1.3.3 Term of reference 2: Frequency of payments

Chapter 5 (Payment design and administration) considers whether the way that assistance is delivered and administered contributes to the financial security and wellbeing of pensioners. The chapter examines the current components of the total assistance that is provided to Age Pension, Carer Payment and Disability Support Pension recipients. Its focus is the balance between regular and one-off lump-sum and supplementary payments, and arrangements to improve flexibility and financial security for pensioners. It also considers ways in which the delivery of assistance could be simplified to reduce complexity for pension recipients.

1.3.4 Term of reference 3: Concessions and other entitlements

The third term of reference is discussed in Chapters 5 (Payment design and administration) and 6 (Concessions and services). Chapter 5 considers supplementary payments and Chapter 6 focuses on the role that concessions and services play in providing targeted and cost-effective support for those with high needs as a result of illness or disability.

Chapter 6 discusses concessions and services separately, reflecting the fact that they are different policy levers. In relation to concessions, it discusses issues around health care concessions, and the targeting and sustainability of the existing system of concession cards. In relation to services, it discusses the service delivery reform agenda being developed under the auspices of the Council of Australian Governments, and long-term funding and sustainability issues. It also discusses implications for informal care.

1.3.5 Sustainability and targeting

The Review found that it could not address its terms of reference adequately without considering the sustainability of the reform directions it has identified. Chapter 7 (Sustainability and targeting) discusses the longer-term sustainability of the reform directions identified for pensions. It examines the impact of the income and assets tests on adequacy for part-rate pensioners, issues around targeting, and incentives for people to save and participate in the labour market. Chapter 7 also considers eligibility rules for pensions, including the Age Pension age. In particular, it looks at the impact of changes in the Age Pension age on sustainability and retirement outcomes, and the interaction of the Age Pension with other elements of the retirement income system.

- These include the DVA Age Service Pension, Invalidity Service Pension and Income Support Supplement for war widows; as well as two closed FaHCSIA payments, Wife Pension and Widow B Pension; and Bereavement Allowance, which is a short-term pension payment.

2. Context and challenges

It was not possible for the Review to develop considered views on its terms of reference without taking into account the role of the Age Pension, Disability Support Pension and Carer Payment in Australia’s broader social protection system, and the social and economic context in which the Review has been undertaken and how this context is likely to change in the future.

This chapter discusses the nature of Australia’s pension system and how it fits within the broader social protection system. It outlines the characteristics of Australia’s system and the ways in which it differs from those in other OECD countries. It then considers the effects of demographic change and the ageing of the population because these long-term trends will have a major impact on the Age Pension, Disability Support Pension and Carer Payment.

This leads to the identification of five major challenges that the Review considered as a part of its analysis of its terms of reference: the global financial crisis, sustainability, the management of risk in retirement, workforce participation incentives and interactions with the broader tax-transfer system, and complexity.

This chapter concludes with a discussion of how these considerations relate to the work of the Australia’s Future Tax System Review Panel, including its report on retirement incomes.

2.1 Australia’s system of social protection

The Age Pension, Carer Payment and Disability Support Pension are part of a broader social protection system designed to assist individuals and families to manage risk and change in their lives.

Australia, in common with most other OECD countries, has developed a social protection system that involves a combination of:

- basic income support for those who are most at risk of falling below an acceptable standard of living

- compulsory schemes that manage the risks and smooth income over the course of an individual’s life. The most significant of these is the Superannuation Guarantee, which is designed to provide higher living standards in retirement linked to a person’s employment earnings. In addition, there are insurance schemes such as workers compensation, third-party motor vehicle insurance and medical indemnity insurance which variously seek to ensure a person is compensated for pain and suffering, medical costs and economic costs following an accident or similar disruption

- support for private savings and asset accumulation, including home ownership and other mechanisms that allow for private provision for the management of risks and assist in smoothing incomes

- direct government expenditure on infrastructure and access to goods and services, such as health, education, disability and community services.

The first three of these are often referred to, in the context of retirement income policy, as a ‘three pillar’ system. The Review considers that focusing solely on the traditional three pillars runs the risk of downplaying the role of services. Having effective services is critical to achieving a balanced income protection system that has the flexibility to meet the diversity of needs and life-cycle experiences of the pensioner population.

The Review has used the term ‘income support’ to refer to pension payments and associated supplementary payments. The term ‘income protection’ is used to refer to the compulsory and voluntary mechanisms that in combination with income support help smooth an individual’s income over their lifetime and across transitions. The term ‘social protection’ is a wider notion that the Review has used to refer to the whole system of income support, income protection, and concessions and services that assist individuals and families to manage risk and change.

2.1.1 Income support

Australia has historically focused to a greater extent than most other OECD countries on providing comprehensive, conditional, basic income support to those who are most at risk of falling below an acceptable standard of living at a point in time.

- Access to income support is determined by targeted eligibility requirements and means testing (it is not, for example, a right accrued from having worked or having paid tax).

- Unlike most social insurance systems in other OECD countries and private savings mechanisms such as superannuation, the level and duration of payment are not related to past earnings or work history.

Compared with other OECD countries, the Australian tax-transfer system is highly efficient in redistributing resources to those with least means. Among the 27 countries for which data are available, Australia has the highest proportion of public transfers flowing to the quintile of the population with the lowest private incomes. Australia also has the lowest rate of direct taxation in the group of 19 countries with data on this (Treasury 2008).

The adequacy of the Age Pension, Carer Payment and Disability Support Pension in performing this basic income support role is the central focus of this Review.

As discussed in Chapter 3, the Review has defined adequacy as ‘a basic acceptable standard of living, accounting for prevailing community standards’. While the Age Pension, Disability Support Pension and Carer Payment perform a number of roles in the income protection and social protection systems, the Review considers that providing adequate income support to those with little or no private means is the most important role of these payments, both now and into the foreseeable future. This is also an area where reform is needed. There are significant aspects of the current structure and rates of pension, in particular the treatment of single pensioners who live by themselves, that do not currently meet the needs of Australian pensioners.

2.1.2 Income protection

The Review recognises that pension payments cannot be considered in isolation from the other mechanisms that form part of Australia’s system of income protection, especially those components with which the pension system directly interacts.

The Age Pension and superannuation

The introduction of the Superannuation Guarantee in Australia made income protection for retirement more widely available to Australian workers. The Superannuation Guarantee provides a mechanism that links retirement savings with a person’s earnings and level of engagement with the workforce over their lifetime. The Superannuation Guarantee reduces the risk of ‘myopic’ behaviour (that is, individuals not saving enough for their retirement), and thereby helps smooth income over an individual’s full lifetime. However, because it is based on private accumulation plans it does so without guaranteeing a specific final level of retirement income.

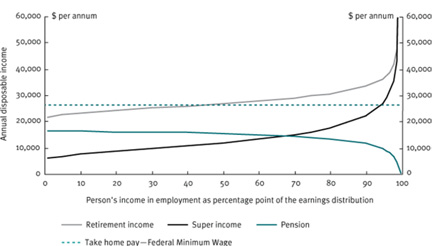

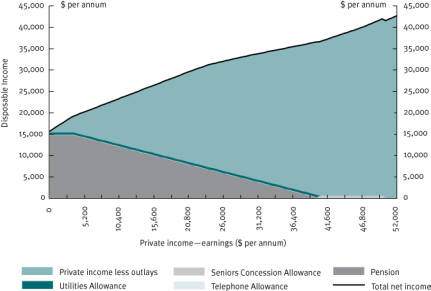

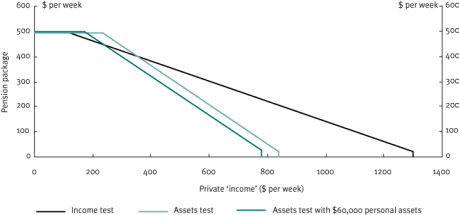

The Superannuation Guarantee was designed and operates as a supplement to the role of the Age Pension in providing retirement incomes. Consequently, it increases the level of individual income in retirement to above what would otherwise have been provided through the Age Pension and private savings alone, and most retirees will continue to receive a substantial level of the Age Pension across their retirement. This is modelled in Chart 1 which shows, for full-time, full-career workers, the relative contribution of the Age Pension and the Superannuation Guarantee to their retirement incomes.

Chart 1 Retirement incomes—contribution of the Superannuation Guarantee and Age Pension (modelled results under full superannuation guarantee)

Notes: Model parameters at Appendix E. Average annual retirement income is given in earnings discounted terms, that is, relative to the income of employed people.

Source: Review modelling.

The maturing of the Superannuation Guarantee will see:

- a strong ongoing role for the Age Pension as a significant part of retirement incomes. Treasury estimates that the Superannuation Guarantee will only reduce the total value of pension spending by some 6 per cent

- a pattern of earnings in retirement that, while linked with employment earnings, is moderated by the interaction with the Age Pension. As a consequence, the effective retirement ‘replacement rate’ of lower income earners will be higher than for those on higher incomes, although those on higher incomes will continue to have higher retirement incomes relative to the community standard

- a proportion of retirees with disposable incomes above those earned by some low-income workers. A consequence of this is that some workers will be paying tax on levels of income lower than the incomes of those who are drawing part of their income from the pension. (This already occurs in some cases under existing program settings.)

Of course actual retirement incomes will vary significantly from this theoretical outcome, depending on people’s workforce experience and in many cases that of a partner, and their private savings. Treasury modelling suggests that by 2050:

- 45.3 per cent of the population aged over 65 years will receive a part pension

- 28.3 per cent of the population aged over 65 years will receive a full pension

- 26.4 per cent of the population aged over 65 years will not receive any pension income at that point in time (although some may at a later point in their retirement).

What this means for the Review is that reform directions for the Age Pension need to take account of policy settings for superannuation, including the impact of changes on Superannuation Guarantee outcomes and the impact more broadly on incentives to save for retirement.

In addition, Treasury modelling underscores the importance of the Age Pension’s role as a safety net. Many of the 28 per cent of Australians aged over 65 years who are expected to be on the full rate of pension in 2050 will have few if any assets or private income. They will therefore be entirely, or nearly entirely, dependent on the Age Pension to achieve an acceptable standard of living. This group will include people who have been reliant on income support for much, if not all, of their lives because of disability or other factors, such as caring responsibilities, that have prevented their participation in the workforce. In other cases, they will be people who, due to longer than expected longevity or unexpected costs, have exhausted their retirement savings.

The implication of these issues for Age Pension means testing is examined more fully in Chapter 7.

Disability and caring

Disability Support Pension and Carer Payment are the principal forms of income support for people with disability who are unable to support themselves through employment and for people whose caring role limits their employment opportunities, where family incomes would otherwise be insufficient.

There is also a range of private or mandated forms of support such as workers compensation arrangements and motor vehicle insurance systems, as well as income protection and related insurance. In the short term, for some employees, workplace-based sickness and carer leave provisions can provide full income replacement when they are ill or need to care for a family member.

However, in contrast to the Age Pension, which is part of a wider income protection system for retirement, the Disability Support Pension and Carer Payment generally operate as safety nets in cases where private income protection mechanisms are not available or have been exhausted. Rather than supporting mechanisms that operate to smooth income over an individual’s lifetime, the Disability Support Pension and Carer Payment focus almost entirely on providing a basic acceptable standard of living for people who have little or no private means.

Chapters 6 and 7 look at these issues in more detail.

Women

The majority of pensioners in Australia are women. Currently women account for 57.4 per cent of age pensioners and 68.8 per cent of those on Carer Payment. While the proportion on Disability Support Pension is lower, at 43.8 per cent, women account for 48.6 per cent of the new entrants into this program, in part reflecting the impact of the increasing Age Pension age for women. Around 55.7 per cent of women on these pensions are single, compared to 40.3 per cent of men.

In large part, therefore, the issues considered by the Review have particular importance for women. The Review notes that while many of the issues and reform directions identified affect women and men equally, the different life experiences of men and women can create significant differences in their experience of the income protection system. In particular, many women have major responsibility for unpaid caring and domestic work, are more likely to have broken patterns of workforce participation and to have lower income and fewer assets.

- Women’s longer life expectancy means that they are more likely to be reliant on the Age Pension for longer than men; 71.8 per cent of single age pensioners are women.

- On average, women on pensions have had less engagement with the labour market than men. This means that for many women engaging and re-engaging in the labour market presents particular problems. This can become more difficult for those who become single due to marriage breakdown.

- For many women this broken workforce participation results in lower levels of personal assets, including superannuation savings. While for those women who are members of a couple account also needs to be taken of their partner’s assets, for those who are single this is likely to have a significant impact on their wellbeing in retirement.

Analysis by the Review indicates that among the current population the level of superannuation assets varies considerably. There are particularly marked differences by gender, labour force status and age. Men have considerably higher levels of superannuation than women across different age categories of the population. Some of this is related to levels of earnings, with some groups, for example ‘middle-earning women’, having levels of superannuation assets much more closely aligned to men than other groups. However, women are disproportionately represented in the lower earnings group, in part because of part-time employment. When relationship status is considered, lone mothers have much lower superannuation assets than other women.

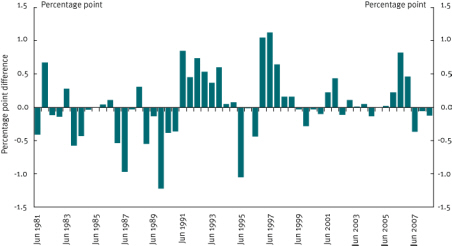

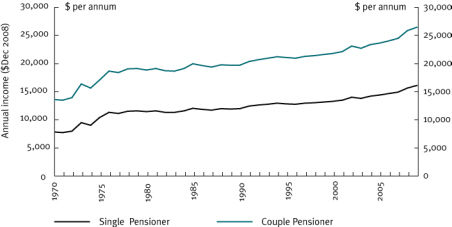

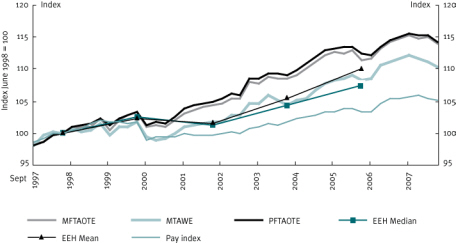

- This situation can be made more tenuous due to women’s earlier age of retirement and eligibility for the Age Pension, and their longer life expectancies than men. Together these mean that while assets are often accumulated over a shorter working period, which may also be punctuated by periods of caring and part-time work, they are needed to support a longer retirement period.